John Newsom in his studio, 2022.

Photo Credit: Jonathan Mannion

Combining realistic representations of animals and vegetation, Abstract Expressionism, and hard-edge geometry, John Newsom’s paintings explore our intricate and complicated relationship with nature. I spoke with John about his origins, his practice, and his upcoming exhibitions – a mid-career retrospective at the Oklahoma Contemporary Museum and a two-person show with Raymond Pettibon in Palm Beach.

Continued from Part 2

Nathalie Martin: It's also interesting that your first encounter with art was through Rauschenberg and Warhol and kind of all the guys that sought to “break the rules,” then going to school and studying the rules yourself, is a really unique way to get into it or to get into the history.

John Newsom: Yeah, definitely. Definitely, because there's a generation in between. If you look at it really by decades and things, there was a generation in between there that was such an incredible, momentous time for painting in the eighties. So the Pop Art that I was really looking at, it came earlier, when we were moving out of Abstract Expressionism into Pop. Like real early Pop into middle Pop. That was a really interesting period, but it was also a very popular period. So that's why I was able to get access to it in rural Oklahoma because I couldn't get to some of the things that were happening in the European context, or even the Far East, which I eventually made it to. I studied abroad and lived in Kyoto. I was in Yokohama, Osaka, Tokyo, and then I was down in Mexico City for a while, around San Miguel and Palenque. So I traveled a lot. I was very interested in broadening my knowledge. I wanted to get the knowledge. And so it wasn't exclusively linear like with the New York context. But for me, it's always been about the journey.

John Newsom, The Bright Side, 2017. Credit: Oklahoma Contemporary Museum

I've done a lot of exhibitions in Los Angeles. I've had good experiences in LA. I’ve always been based in New York and coming up I never had the dream of going to Los Angeles. I always knew I wanted to get to New York and it's a different place to paint here. It's just a little different than it is in LA. And it’s not to make a value judgment. It's just to say that it's a different type of context to be painting in. I think that's benefited my particular type of work again because of the tactility of the surface. That's kind of a uniquely New York historical way of approaching the canvas. If you look at my work, for the most part, the works are rather large in scale and they're also very tactical. They're tough, they're heavy, and they're physical paintings. So I always found it kind of a nice juxtaposition when I would go to Los Angeles and see friends and artists out there and shows where it became about light and space. It was all about light and space and atmosphere and it was amazing. It was a trip, but then I get back here and it was like we're back in this earthen realm of the physical, up-in-your grill surface structures. I love that because I feel like paintings are made as much as they are painted. I mean, there's the idea of the mark.

NM: I agree and see that in your own work.

JN: There’s a certain attribute about mark-making in New York that is different than anywhere else, and I love it. That's why I continue to be encouraged by the energy of it. I was talking with the painter Ed Moses about this one time, and he was an interesting painter because although he was in Los Angeles, he was a very physical type of painter. His surfaces were very physically driven. So if he had stayed in New York, he would’ve had a very different history. And if a painter like Brice Marden had gone to Los Angeles, with his type of work, those Cold Mountain paintings would have a totally different feel to them. I just think it's interesting to really take note of the context of where it is you are painting in a landscape. Corot was painting in a certain landscape, Turner was painting in a certain landscape, Van Gogh too, and it's just all this kind of stuff. So it's really fascinating. I am so blessed and grateful to be able to have the opportunity to get up every day and go to the studio and do what I do.

NM: Where is your studio?

JN: My studio right now is located at Mana Contemporary. So I'm actually in Jersey City. But my studio was in Soho previously for twenty years. That was the right amount of time to be in Soho. I'm glad I was in Soho when it was like that. Especially in the nineties, because coming into Soho in 92, we got the backwash of what was there, but there was enough. From 92 to 95, it was still jamming. There were still unbelievable, pivotal types of presentations happening with exhibitions there and these artists and it was amazing. It was amazing. Things shifted, which is okay.

John Newsom in his studio, 2022.

Photo Credit: Jonathan Mannion

NM: As they do.

JN: Yeah, the city doesn’t go anywhere, you just get offered different options, but being there at that time was just incredible to come in on that period, you know? So listen, every generation comes in on their own time.

NM: That's what I tell myself at least.

JN: Yeah, for sure. So I was planning a move of studios and my wife and I found out we were pregnant with our first child and we had been living in Soho prior to having kids. So we moved to Brooklyn and we live in Park Slope. I decided to move my studio, and through a chain of associations I was offered to take a look at the current space, and I built it out. I really like it. I’ve been at the current studio maybe six, seven years, something like that. It's a long commute, but I'm glad I have it. I walk, I take the trains. I love living in a walking city. As a painter, I love it. That's another reason why I could never be in LA. There was an apartment I had access to for four years through the gallery I was with in LA and I'd stay there and I'd either get a car or have a driver or some way to get around, but I never really drove. You get to run into people here. You want to have experiences. You feel a part of the city, you feel closer to it. So I walk, I take the trains. I don't go to the gym, but I go to the studio. It helps you a little bit. But it's all good. Everything's good. Everything's in a real good space. So yeah, totally. I'm happy.

NM: Good. I want to talk about your influences too. Your fauna definitely reminds me of Audubon and your backdrops remind me of Pollock or Mitchell, and your flora reminds me of Kahlo even.

JN: Well, I love all those artists you’re mentioning. It's really important to do two things. It's really important to address your influences, to work with and through your influences. You have to do that, but you have to literally work through your influences until it’s digested fully and it's yours now.

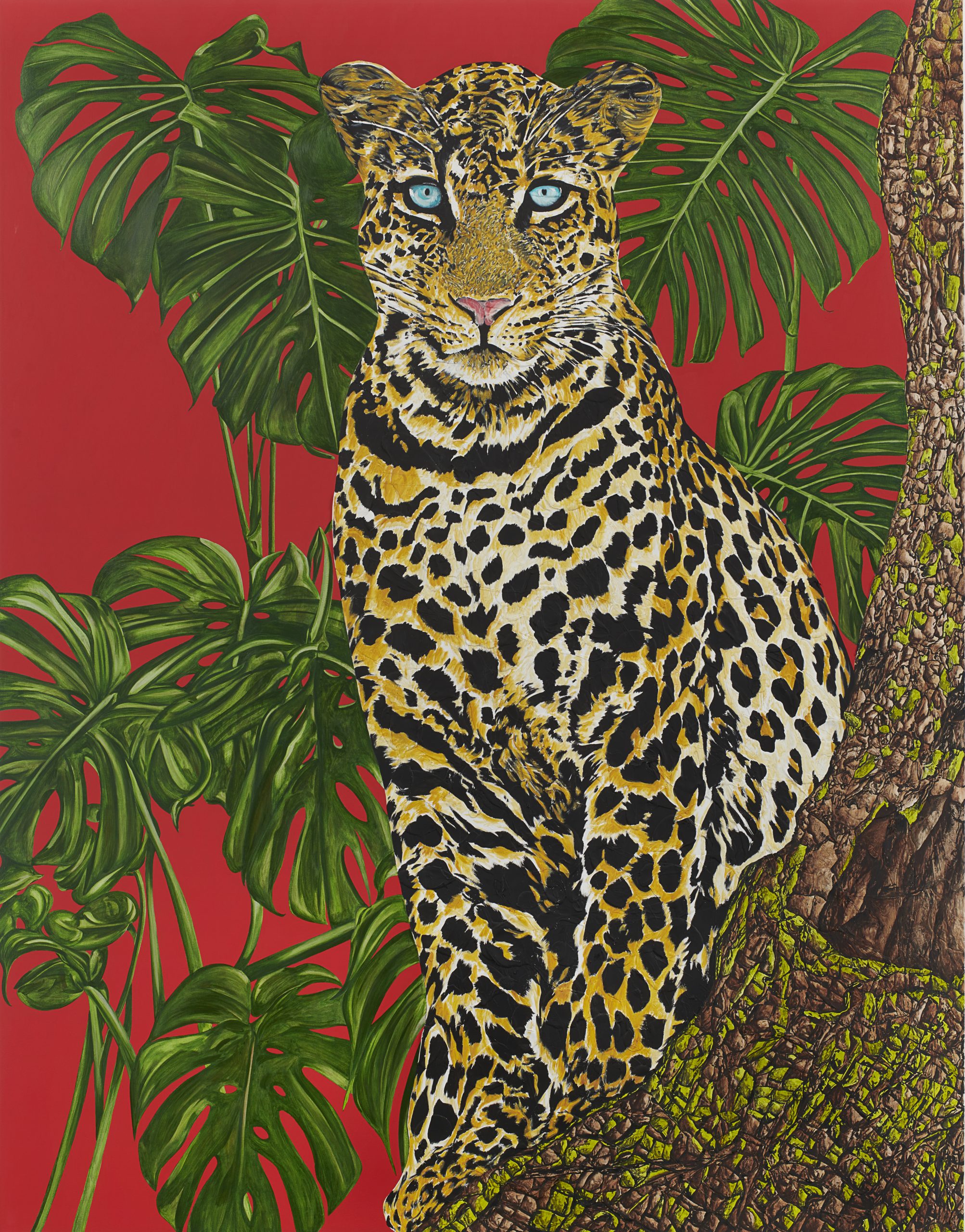

John Newsom, Keep Watch, 2020. Credit: Oklahoma Contemporary Museum

NM: Absolutely, so you’re not just regurgitating.

JN: You have to do that. I mean, the Greats study the Greats in order to be great. You have to do that in anything, in music, sports, entertainment, in writing. Again, because I kind of started out early, I got to go through a lot, and quickly. I gathered a lot, I went through a lot. When I say a lot, it wasn't like I was looking at a dozen artists. I was looking at hundreds of artists. Really, hundreds of artists, trying to see what it was all about. And there are many, many false starts. You're not going to hit it out of the park every time. There's going to be a lot of strikes, and you have to embrace it. Sometimes it's like, “This is interesting, but it's kind of a dead-end,” and so now I’m going to go over here and, “Oh, wow, this is happening.” But you have to keep an open mind, always have to keep an open mind. You never know where it's going to come from, where that spark is going to be. So you're mentioning artists like Audubon to Joan Mitchell, which is interesting. Who the hell is thinking of that together? You know what I mean? You make an interesting point because it's like, “I want it all.” Going back to Rauschenberg, when you look at Skyway, it's like he was cramming everything he could into every square inch of that painting. That’s what I love about Rauschenberg and certain other artists that I'll get into – the level of generosity. I just love when I walk into a show, wherever it is, I'm like, “Oh, wow. Whoa.” You know, it's just, “Oh my God, look at this!” So if I'm flipping through Artforum or whatever, I see an announcement for an exhibition by a certain artist, then it's like, “Oh shit! I can't wait to see this!”

NM: Me too! And when it hits, it hits.

JN: Oh man, when it delivers? Because it might not deliver. But when it delivers, you know, it's like watching Pacino in a film or something…. and it delivers! You walk in and you're like, “Wow, this is it!” It didn't happen overnight. Paintings don't make themselves. You've got to get up, get your coffee, get in the studio, grind, flow – however it gets done – and you have to paint every day. This reminds me of a quote by Alex Katz that I've always loved. I really admire Alex Katz. He's amazing. And he said, “Go to the studio, paint 10 hours a day every day for 10 years, and then come see me.” And that's just such a pretentious, badass, New York quote. That's just awesome. So that's what I did. I painted 10 hours a day for 10 years. And then I went to see him. He gave me a drawing of his wife Ada reclining on the beach, and my wife has it hanging in our bedroom and it's signed: To John, Love Alex. So I took his advice and if you're a painter like that, I'm giving you Alex Katz's advice, because it was really good advice. Just get in there and grind, and that's really it. You're also going to find out a lot about yourself and if you're cut out for this, because not everybody is built for this nor should they be. It's just following your own bliss, figuring out what that means, and what’s that about.

John Newsom, Solstice, 2016. Credit: Oklahoma Contemporary Museum

So I can get into influences. Certainly, there have been many, many, many, and I gotta tell you, it's at a point now where it's become self-referential in the work. And that's a strange thing to say. It's not completely self-referential, but it's to the degree that… like, the Jasper Johns show just closed at the Whitney, and it's been a very busy time for me and I didn't get to see it.

NM: What! No way.

JN: No, no, no, but it's fine. I'm not stressed about not seeing it because I've seen other Johns’ shows. He’s a great painter, but I’m at the point where I can't see anything right now because I've got to be on my shit. But it hasn't always been like that. There was a point earlier where I would have made sure to see a show like that because I needed to see it. Or I had to see it or whatever, but you know what, I've seen iterations of it. I hope I'm getting this across because it’s an exciting place to be at. It's like, wow, I finally have so much on my plate with my own painting that I actually can’t go see this stuff, but it’s okay. Because I know it, I know what it is. I’ve really enjoyed sharing these stories with you because it’s a time to look back. It’s a time to take a moment of self-reflection and to look back and to take stock and see what things have happened, what paintings exist now that are particularly important and strong in my own lineage, and then see where I’m going with it. Then I'll have a period that opens up where I can exhale and go see something, and then you see what happens. It's interesting, things that you would have never imagined you would’ve been into at a certain period, you're obsessed with, you know what I mean?

NM: Totally. Some of my favorite painters now are artists I originally didn’t understand or like.

JN: And then vice versa, you know, you've got to be like that. You can't just stay on one thing. If you're on a type of painting or an artist as an influence, and you're looking at it and you know it back and forth, it doesn't mean you have to stay on it forever. You can set it down and you can evolve into other things, knowing that it was there. It is there. But you don't have to feel obligated to take it with you everywhere. Not that you should either, because the most important thing is to find your own voice as a painter. You have to work through your influences. You look at Velazquez or Caravaggio or late Manet – this is capital “P” Painting, and you have to get through that stuff. You have to go to the Prado and see Spanish painting, you have to see the Louvre and the French painting. You've got to do all that stuff. I was told that when I was young, and I've been to those places. So you get into a certain moment in your development and then you process it, and it gets better. It just keeps getting better, and you get wiser too, just by doing the work. Because the work leads the way.

Combining realistic representations of animals and vegetation, Abstract Expressionism, and hard-edge geometry, John Newsom’s paintings explore our intricate and complicated relationship with nature. I spoke with John about his origins, his practice, and his upcoming exhibitions – a mid-career retrospective at the Oklahoma Contemporary Museum and a two-person show with Raymond Pettibon in Palm Beach.

Continued in Part 4