An Interview with David Aaron Greenberg (Part 3)

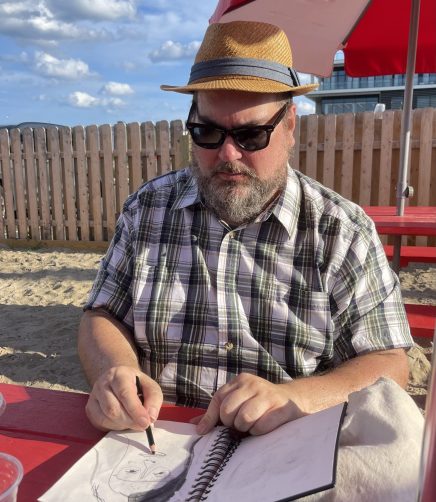

David Aaron Greenberg in his studio

Photo by Pedro Angel Serrano

David Aaron Greenberg is an artist who uses multiple modes of expression. His work has been exhibited in various New York City galleries and is in the permanent collection at Stanford University. His critical writing has appeared in Parkett, The Fader, Art in America and Whitehot Magazine. Along with producer David Sisko, he co-founded Disco Pusher, a New York City songwriting and recording duo. Greenberg graduated from Rutgers University, Phi Beta Kappa. He lives in New Jersey and sometimes New York City.

In the final installment of their 3 part interview, Alexandra Kosloski and David Aaron Greenberg discuss Road Tripping, his project with The Trops, and the inspiration behind it.

Continued from Part 2

AK: How would you describe the local art scene in New Jersey?

David Aaron Greenberg: In Asbury, the literary scene is really vibrant, this “New Jersey Poetry Renaissance” that they call it. The music and the poetry overlap, but not so much with the visuals. It used to be the eighties and nineties artists were in bands, and bands had artists and there was this cross-pollination. And I wish there was more of that.

In terms of the visual, there’s little pockets in New Jersey, it’s very dispersed. You know, there’s real people around me. And I’ve seen young friends of mine that are in Philadelphia, where there’s definitely giant buildings where there’s like 300 other artists, and I would just find that oppressive. I mean, it’s great if you’re young or if you like that, but I don’t want to be around other artists. I want to be around real people. There are people that come into my studio that I meet on the street, literally, and then pose for me. I just recently met a gas attendant at the Wawa, and he came in here. I mean, when they walk in here, their opinion is not some bullshit. They really tell you what they think of your art. They don’t have any preconceived notions. They’re not angling for something.

David Aaron Greenberg

Vibing, 2023

I remember years ago the Italian painter Sandro Chia said, “The greatest way to judge the value of a painting is to just leave it out with the trash and see what happens to it.” Divorced of the context of the gallery or in a museum, if you saw that fucking shit on the street, what would you do? Would you say that’s really interesting or that’s a piece of crap? And I think it’s a really wonderful concept. Like, I sometimes leave my paintings outside to dry, and people ride by and they go, “Oh, that’s really nice.” Leaning up against the wall, drying in the sun outside of the apartment building. You’re not living in the real world if you’re completely surrounded by artists and everything that you do is like: you go to openings, you go to dinner with artists, you vacation with artists and you go to the Hamptons. It’s like you’re living a lifestyle instead of actually making art, right?

AK: You could get out of touch with most viewers.

David Aaron Greenberg: With reality. Just like, dealing with everyday life, the artist is not supposed to be removed from society completely. As Walt Whitman said, he was “one of the roughs”. That’s what made his poetry so great. He was amongst the people. And New Jersey makes you real, no matter what. People do not give a fuck here.

AK: But that’s a really beautiful thing that you were saying. Road Tripping, the project you’re doing with The Trops, you’re not displaying it in a white box, you’re displaying it in the community.

Photo of the artist’s studio

David Aaron Greenberg: Yeah. I’ve talked to the owners of the spaces and had their approval to put it up. So you’re talking with real people that are part of the community that want to encourage art and music and all that. What I really love about The Trops is that it’s very simple, but it’s very revolutionary. It’s like it’s got one foot in the established art world, and it’s got one foot in the real world. And it needs to be in both of those places. And that’s what’s so great about it. To use the technology of apps to to do something that’s not just about making money, but really being part of a community. And there’s a big difference in experiencing something in real time than it is online. I mean, we all love looking at people’s art on Instagram and we love to take videos, but you can’t experience a painting unless you’re standing in front of it. I just recently saw The Cure. I’ve never seen them. And there is something about a live experience, whether it’s music, art, poetry, reading. It’s life, it’s real. I think this young generation right now is relating to that because they lived through COVID. They interact with people and have cravings for real things, real books.

AK: Real connection.

David Aaron Greenberg: You can see real experience. These kids sniff out when they’re being manipulated and being set up.

AK: Can you tell me a little bit of the inspiration behind Road Tripping?

David Aaron Greenberg: I tried to place paintings that seem to somehow relate to the space. It was really easy for the painting in the Scarlet Reserve Room, which is a smoking club. That particular painting I had been painting for a while. I started it on acid. It’s probably the last time I’ll ever do acid because it was just too intense. That was like two years ago. And then the friend of mine– that it was based on– was in the studio, and I said, “Oh, let me pull this out. Remember this experience?” But it was interesting, there was something not right about it. Like, the dimensions were all weird. It was trippy, you know, it was started on acid. And I said, “Let me try to fix this, stand here”. And he’s like, “The only way I can deal with this is if I smoke.” There was something missing in this painting, and he started to light the joint, and I was like “That’s it.” And it became a still life of the actual joint that he rolled. And so, the fact that a painting of mine is in a store arena in an establishment that I totally love, and if it helps promote the place, awesome, because I want this place to thrive. Not only are people smoking weed there, but the atmosphere is amazing. People read poetry and it’s just really relaxing.

Now, The Asbury Park Roastery, that’s a strange little painting. It seems like somebody who needs a cup of coffee.

AK: Yeah, it’s a little moody.

David Aaron Greenberg

Black Eye, 2023

David Aaron Greenberg: Exactly. And Keyport Funhouse, that place is like your older sister’s best friend’s bedroom exploded, and the coolest shit is there. And you’re like, “Wow”. It’s like when you’re young and there’s an older girl and she lets you in her room. It’s a big deal. You’re like, “Wow, this is how girls live?” You know? It’s not a boy’s room. It feels like that when you walk in. It’s a great vibe, and what I put in there is a very small, very beautiful little portrait of the singer Sandflower, who I’ve written with for like ten years now. And I wanted the painting to have the feel of one of those tiny little royal portraits that you see. So it’s the oil is really heavily built up and it’s got tons of varnish on it. And you can sit on a couch and get coffee or homemade lemonade and just lounge in there, and the painting just feels natural. It’s glamorous and beautiful and feminine, and I love it. The other painting I have is in New Brunswick, which is in the George Street Co-op, which is a great place.

AK: I love the George Street Co-op.

David Aaron Greenberg: I don’t remember a time that it wasn’t there. It was such a big deal to actually have a painting in there. I didn’t know if they would agree to it. And the manager was just like, “Yeah, let’s put it up right now”. That one is called “Pop Smoke”. It’s a strange little painting, it kinda looks like the figure is in the smoke. I’ve been going there since I was in high school in the eighties. They have an open mic that they’ve been doing for years in various forms. And it’s a great little thing. It’s a great place to try a new song, for me. It gets you out of your space.

I didn’t make any of these paintings with the idea that they would wind up in these establishments, but the fact that they work in them is really rewarding. At the end of the day, as Stephen Torton says, “We are just all decorators in one form or another”. You know, it’s part of the furniture. And also the notion that they’re not all in one place, that you could literally take a road trip. You can start, let’s say, in New Brunswick and go to Red Bank, then go to Asbury, go to Keyport, come back. That’s awesome, go to the beach, get some coffee, smoke weed. I think it’s cool.

AK: It’s a whole journey. Yeah.

David Aaron Greenberg: It’s a great thing. Ultimately, even if it’s the landscapes that I do, the portraits, they’re all a way to elevate the everyday, every day. People are beautiful. The “road tripping” aspect is pretty funny, too. People travel all around the world and forget about their own backyard. The beauty in the everyday.

An Interview with David Aaron Greenberg (Part 3) Read More »

Interview