Brushes made by the artist, 2013, courtesy of the artist.

Working at the edge of painting, photography, music and film over the course of five decades, Jamie Nares has profoundly explored the relationships between memory, time, movement and thought. I spoke with Jamie about her childhood, her move to New York City in the 1970s, her multidisciplinary practice, and her generous vision of art and life.

Continued from Part 2

COM: And once you moved to New York, it seems that you hit the ground running. When did you begin doing the paintings that you are so known for?

JN: Well, I'd always, like I said been making drawings and stuff. And when the '70s hit suddenly people were able to make a living making paintings. And I had been trying to make films and I just didn't see a way to support myself making the films that I liked. And I didn't want to go to Hollywood. A couple of my friends did. I never really saw the world in narrative terms, it didn't really interest me to do that. I thought it interested me for a while and I tried. I made that film "Rome '78," which was about as close as I ever got to making a narrative film. There's a funny letter I have from someone at Paramount Pictures saying, "We hear wonderful things about your film Rome '78, would you like to come out come out to Los Angeles and meet us?" you know, with the idea of making another movie. And I just wasn't interested at that point because I realized that... I always wanted to do everything. And I realized that you can't do everything and be successful. Although I had a pretty good shot at it. But at that point, at that time, I figured I needed to focus on one thing and get really good at it. And painting seemed to be the thing that I would be most likely to get good at. So, I started painting. My early paintings were kind of all over the place. I had a couple of years where I was really just finding out what it was that interested me. And I started making work that was closer in look to a lot of the expressionist painters that were around then. I made a piece in 1977 called "Red X," which was a big enamel red X on a piece of cardboard, which is still one of my favorite paintings I ever made. Julian Schnabel owns it now, but it's been shown in Gagosian gallery, and in Milwaukee in my retrospective. And it was one of the best things I ever made. Just a simple, bright red, red X, on a black background painted on cardboard. And there's something about the painting that people just love it. Of course, it stood for the kind of negativity that we were awash in, but it was always the negativity that was that aimed towards something better... We were fledgling iconoclasts, but I really believed in something better to come. But I started making paintings and they changed quite quickly.

JN: The thing that really interests me most in painting was the brush stroke. And I figured there was enough happening with no single brushstroke could keep me interested. And it still does, all these years later. But that wasn't until 1992 when I was living out at the East End of Long Island, and I had a studio in a barn, and I was working very happily there. And that's what I really refined what I was doing. I'm working right now on putting together my notebooks in a sort of facsimile edition from that time, because it was a time when I really forged the thing that I was most interested in and started making my own brushes. I started making paintings that were made in one movement. The way I would work then was to make a big brushstroke and if I didn't like it, I'd get down on my hands and knees with a big sponge soaked in mineral spirits and wipe it off and then and then dry it with a rag. And by the time I'd done that, I had lost the muscle memory of what I was trying to do. And there's a lot more work to do that. So, I eventually figured out this way of erasing a brushstroke that I didn't like by squeegeeing it off with the same kind of squeegee to clean a window booth. So now I have a guy with a squeegee while I put down the brush strokes and if I don't like them, he just Bzoop! and they disappear very quickly. And I'm able to get back into it again, trying to make it better.

Installation views, Nares: Moves, Milwaukee Art Museum, June 14-October 6, 2019, courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

COM: I'm interested in this idea of muscle memory because your work seems to be very bodily. In a way your whole-body kind of comes through because it requires so much movement. Do you conceive your works as performative in any way?

JN: Yeah, in that they are the product of an event. They're not performative like I'm performing painting for an audience. I wouldn't have any interest in making a painting in public... They are performed paintings, preformed, performed paintings. And they require a certain centering of the mind, which I like. I have to get to a place where I am not leading the brush, but I'm not following the brush. There's this edge between those two, leading and following, and it's a place that I have to reach. And that's the magic can happen.

COM: That's interesting. It's sort of a dance in a way.

JN: Yes, dance is very important. Rhythm, dance, music, photography. The paintings are made in a... what you see, the brushstroke is made in the same kind of time frame that a photograph is taken. It's just a matter of seconds. So, it's like you're capturing a moment in time, like a photograph. And I like that the viewer can kind of participate in that moment of discovery that I had when I made the painting. It all there, it's just like [being] naked. I don't hide anything. I don't go back and correct anything. If there's something wrong with it, I wipe off the whole thing and begin again. Of course, they have a sort of photographic look, too. It's always been a conversation between photography and painting ever since photography was invented. The dialog of one kind or another. And this is my dialog. It's to paint like I was taking photographs. There's that quote from Kazimir Malevich, where he says the painter has to paint the photos of his mind.

COM: That's beautiful. Is that how you see your work?

JN: In one aspect, yes. But it's like capturing a moment of thought and a moment of a feeling or a moment of some kind of congruence between myself and any given moment. I said somewhere that you could connect all my paintings from one end to the other and you'd have, like, the story of my life in paint.

COM: That's a great idea for an exhibition.

JN: Yeah.

COM: What do you consider to be your subject matter? Is it about memory time, movement, music, or all of them?

JN: All of the above. Memory, time, movement, music, thought. It's making manifest, manifesting an abstraction of a moment in time using the traditional tools that a painter uses: a brush, a canvas or surface of some kind, and paint. And I've come up with my own versions of those tools and make my own brushes and mix paint in a way that's a bit unusual. And I prepare my surfaces. My whole practice of painting is something that I think I'm the only one who does it. But it was all necessity, you know? My invention is always because of necessity.

COM: It allowed you to achieve something you couldn't with the readily available materials.

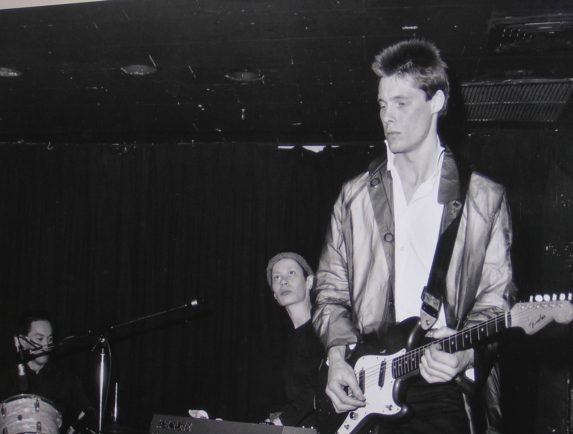

Jamie Nares playing with the Contortions, 1977, Betsy Sussler.

JN: Yes, I couldn't buy a brush that does the things that my brushes do. I just repurposed things to suit me the way I wanted it to be. There's something very Zen about it, my practice. There's something kind of tantric or shamanistic about it, too, in some ways. And there's a lot of influences.

COM: I'd love to talk about your influences.

JN: Well, you know, I've been influenced by just about every other artist ever met. Something rubs off, even if your influenced in a negative way. And then I'm influenced by the things I see, the things I see other people doing. I was very influenced by my peers early on because it seemed like we were kind of forging something, figuring something out together. Those were good times, in a way. Oh, they were good times. Those seventies were rough too, the city was dangerous, and nobody had any money. It was a tough time. But it was great.

COM: A formational period.

JN: Yeah, so my influences are every place and everything I've ever done or been or heard or saw. It all filters through to who I am and what I do.

COM: That's a very generous way of looking at it, and very true about life in general.

JN: I think so, yes. It's life in general that interests me. I mean, there's so many things going on in this world.

COM: It’s a matter of slowing down and looking closely.

JN: Yes.

COM: You had a major retrospective a couple of years ago at the Milwaukee Art Museum. And now you're returning to London after so much success. How do you see your journey from this point in your career?

JN: Oh, it is very strange. It seems like if you make it to a certain age, people suddenly get interested in you. I made it to an age and survived. A number of people I've known who gave up or passed away or just disappeared. There's something just by having stuck around. People like you when you stick around and keep going. I do have this thread of my own personal histories and it seems to be interesting to people right now. But it also seems that people are interested in that period that I was talking about when I said I was coming of age, the seventies and eighties in New York. And I have something to say about that just by virtue of being there, you know. Oops, I forgot the question.

STREET, 2011, HD video, 61 mins.

COM: Oh, well, it must be interesting to look back at so many decades of production, having that perspective.

JN: The show in Milwaukee was just great because we worked on it for about six years. Marcelle Polednick who curated it and became the director of the museum during the time that we started working on it. So, everything just came together nicely, and she was so wonderful and supportive, and she's the first one who really saw me and understood what I have been doing all my life. She put this show together and curated it, and we organized it thematically rather than chronologically. It was really a lovely show for me to wander around. The effort that people put into it, the exhibition designer, everybody. It was a magical time for me.

Plus, I'd just come out. I mean, it was a very intense time. I had just announced my true nature to the world, and I'd had a show that opened five days earlier in New York and I had showed up as my true self, so to speak. And had spoken to all the gallery and announced, it was like a formal announcement, that sort of thing. And I went down to Milwaukee five days later to start installing this show and was greeted with a newspaper article calling me the inadvertent advocate. I was like, "No, I'm not an advocate, I'm just trying to figure out who I am." And of course, it was a surprise for everybody. And I could see these two trajectories converging. One was the retrospective with my life story, in a way. It was like these two trains, the other one was my transition that was coming to a head, this new life that was happening. And I could see they were going to collide, which they did at the Milwaukee show. It couldn't have been a more perfect time and place. And Marcelle to her endless credit just jumped right on board and supported me like a 100% and sent out memos to everyone in the museum, and changed some of the bathrooms to gender neutral, and did all these little things to make it nice for me. People were so wonderful. It was just a wonderful experience.

COM: That's great to hear. Big moment.

JN: Yeah, it was. It was a very big moment for me. And I think very fondly of it. There's a wonderful catalog from that show. Just "Nares: Moves," that's it. But my transition is an ongoing process.

COM: What keeps you going today? And are there any projects that you're excited about looking towards the future?

JN: You know, it's very strange because I have so many things I want to do. I've never had so many ideas and thoughts and things I want to do. And it's kind of tragic that I'm declining physically at the same time... It's more difficult for me to do the things I want to do. A lot of the things I want to do I can't do, which is frustrating. But you know then I just do things I can do. I'm perpetually motivated and interested. Something keeps me going. It's just the same thing I've always had. It's like a life force, I guess.

COM: That same sense of direction we talked about at the beginning.

JN: Yeah, yeah, I think so.

Continued from Part 2