Red Handed, 1971, color photograph, 12 in x 17 1/2 in.

Working at the edge of painting, photography, music and film over the course of five decades, Jamie Nares has profoundly explored the relationships between memory, time, movement and thought. I spoke with Jamie about her childhood, her move to New York City in the 1970s, her multidisciplinary practice, and her generous vision of art and life.

Continued from Part 1

COM: You mentioned you always felt like you had a sense of direction or that you knew what you were doing and where you were going.

JN: It's true.

COM: That's pretty unique for such a young artist.

JN: Maybe, yeah. I read so much about art, and about the art being made by the artists in downtown New York, and California, and other places, too. And in Europe. It was a very lively, inventive time for the visual arts I think, the whole dematerialization of the art object, the way of seeing things. There was so much going on, and I knew about it. I read about it even if I wasn't really involved with it in England. I was doing things like, I had a job as a motorcycle messenger delivery person and I signed my name across London traveling along roads and then marking where I went on the map and put my signature right across London, things like that. Humorous. But I did some really beautiful things. Did you see a book of mine, a Rizzoli book?

COM: Yes.

JN: Under the dust cover there's a photo of me with red hands which I love. And it was it was just called "Red Handed." I just painted my hands red, and I was standing there with a hat on. There was another piece I made when I knew I was going to be coming to the States. And I took the little schoolboys plastic map of the United States, the kind that you put it in a book and then trace around and you got a map of America and then you can color or something… I took the edge of the East Coast and embossed it in my forearm on the place where you commit suicide, the inside of the forearm... I called it "A New Vein." So, it was like a little death going and something new. That's a nice piece. I like that. And of course, the piece itself is just two photographs, one where I'm pressing this thing in and the other one where you just see the bust outline of the East Coast.

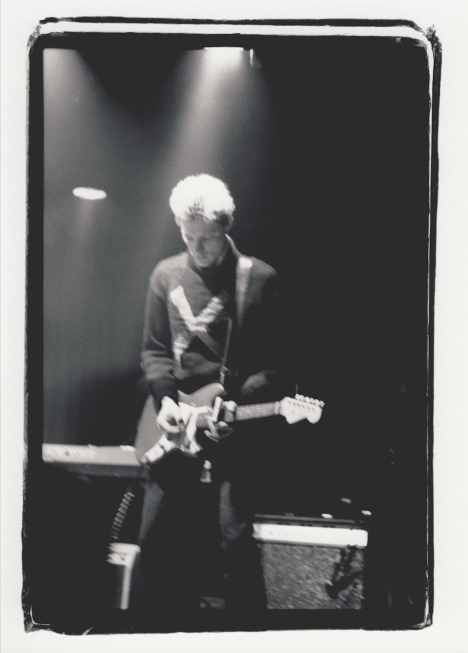

Jamie Nares playing with the Contortions, 1977, Betsy Sussler.

COM: Did you feel as a young artist that you were constantly inventing or reinventing yourself? This piece seems to suggest something around that.

JN: I would say so. Like every day something new going on and there were very rapid changes happening. There were very rapid changes happening in the world and inside me. But I was saying that around 1976-77, we kind of revolted against the art world and we didn't want to show our films in the established art houses. We opened our own cinema. And it was called the New Cinema. It was on St Mark's Place, and we had something called an advent TV screen, which was a humongous projector. And you could plug a video deck into it and see your film projected onto this old TV shaped screen that was concave. So, if you were standing, like right behind the projector in the perfect place, you could see what was going on. But if you were anywhere off that line, the image deteriorated. And I remember Amy Taubin who became a great friend of mine later, writing our first review she said that the image was like bent pink soup. And that became a kind of refrain for us. Bent pink soup, is still think of it. And she thought we were just a scam to make money. And she missed the point entirely. We were very dedicated, and we did want to make money. We wanted to be sort of in the real world. We didn't want to be in the alternative world. You had to pay to come into the movie theater. $2. There were no freebies. It's great. It lasted for about seven months, and we closed it when it was at its hottest. I forget why exactly; I think we just didn't want to become an institution. We saw a kind of looming bureaucracy that was going to be involved if we kept it going... We just wanted to feel like we were in the real world, making our living doing what we did.

COM: You said that after this period, things started changing and the groups began dissolving. How did that transition into focusing on your own practice go for you?

JN: Well, I was never the best one at being the member of a group, because I just wanted to do my thing. And, out of those groups Colab was incredible. It was wonderful, [we put some] great shows. And I have a lot of friends that were in there, but I just was more interested in doing the things that I felt compelled to do. It seemed that there was a kind of urgency to get the work made. And around '77 music became very influential. That was when the punk bands from England became very important to us. And then the music that was happening in the States, too. And next thing I knew, there was a kind of dissatisfaction... How do I put it? The possibilities seemed to be closing down a bit or something. And so, when James asked me, do you want to play guitar in my band? I said, "Yeah, sure." Did you see the film Blank City?

Installation views, Nares: Moves, Milwaukee Art Museum, June 14-October 6, 2019, courtesy of Kasmin Gallery.

COM: I don't think so...

JN: Yeah, it's good. It was made by Celine Dahnier. The first half of it is a documentary of the scene that I was in. And then there was another scene with people who would they call themselves "the cinema of transgression," and their names are going out of my mind right now. But the first half of the film is really good, and in it, Charles Leary, my old buddy who I don't talk to anymore, says, "anybody who is doing what they knew how to do is very suspect." And there was this conscious doing of things that you didn't know how to do because it made them completely fresh. You know what I mean? We delighted doing things we didn't know how to do and bringing ourselves to it. It seemed like the way to make something really different. And certainly The Contortions, when we first appeared, we made quite a splash. Nobody had heard anything quite like it.

COM: Speaking about trying new things. When did painting become something you were interested in?

JN: Well, like I said, I painted when I was young. And I had painted really up until the time I went to school in London, right through high school. I was blessed with the most wonderful art teachers at the schools I went to. It was wonderful. It was so it was so great to have these teachers and I was painting then. But I was also doing other things, like I would go out and paint the grass green, paint the bricks red, or in a piece of home I'd penciled in a rectangle on the wall our house. And it had some prints and scars of things on it and I very carefully painted it. It was what was there exactly... It was like kind of like putting makeup on or something. I just painted what was there, but it looked a little different with this penciled rectangle around it. My mother wanted to get rid of it so badly, but you know, she knew she couldn't do it. It lasted for a long time; she really didn't like it. But I was always doing things, you know. As a kid I was always doing things. And my parents were incredibly forgiving. I took over my stepdad’s old 16mm home movies that his father in shot of him with his brothers and sister, and I put them on a piece of wood and hit them with a blowtorch and made a kind of celluloid Jackson Pollock. It was great, it was really good. But he didn't complain at all. I never heard a word of complaint. He'd come home to find that I raided his drawers, taken out his pipes and glued them to a chessboard and spray painted them silver or something. I was a little bit of a terror, but it was a creative terror, you know. I think they thought that it was good that I should be doing this because I was doing something I wanted to do, and I was a disaster in all the other areas.

Back Then, 2021, oil on linen, 66 x 54 in.

COM: They sound supportive and forgiving.

JN: They were supportive and forgiving to Nth degree, I have to give them that until eternity. They were wonderful. And then there was a lot of music. My stepfather played the piano. That was when I was three. And actually, my stepdad bought a beautiful old gypsy caravan, and it was just like a house on wheels. It was a spectacularly beautiful thing. And they painted it in bright enamel colors. So, it was like this enamel jewel that he put on the side of the house, and that became my studio. My first studio was a gypsy caravan. I have a photo of it, it's really nice.

COM: How old were you when you had your first studio?

JN: Like ten. I was doing things like I got a chemistry set for Christmas and I very quickly found out, that if you mixed all the chemicals together and put them in a test tube and put a cork in the top and then hold them over a burner, they would explode and make this incredible multicolored splatter on the ceiling. I amused myself doing that for a while. Gosh, poor parents. Wow, I'd never spoken about this stuff before.

COM: It sounds like a like a wonderful creative childhood.

JN: Yeah. I think it was, I really do.

Working at the edge of painting, photography, music and film over the course of five decades, Jamie Nares has profoundly explored the relationships between memory, time, movement and thought. I spoke with Jamie about her childhood, her move to New York City in the 1970s, her multidisciplinary practice, and her generous vision of art and life.

Continued in Part 3