The filming of Sweet Thing, a film by Alexandre Rockwell, 2021

Filmmaker Alexandre Rockwell is perhaps best known for his works, In the Soup and 13 Moons. His ability to bring to the screen colorful characters that are both intricate and flawed, as well as his use of classical techniques and sheer creativity to tell stories has made him one of the most well-respected figures in independent film.

In their interview for the Trops, Alexandre Rockwell and Alexandra Kosloski discuss taking risks in art, community, and the making of Rockwell's anticipated new film Lump.

Alexandra Kosloski: Could you talk about your latest unreleased film, Lump? It was a really beautiful film, and there's a lot of interesting things about it, one being that it was shot on iPhone.

Alexandre Rockwell: Yeah, it's weird. I really like film. I like shooting on 35 or 16 millimeter or even 8 millimeter. I've always done that, even with low budget films. This one I had zero money on and I had to shoot a lot inside a car. I was trying to figure out what would be the most mobile way to shoot. I figured I would give the iPhone a try, even though I really resisted, resisted, resisted.

This film is black and white, so that simplified things– I don't have to worry about a color palette, I just had to think of tones and contrast and framing. I was able to overlay film grain on it, which has kind of an organic texture, almost like sand or stars in the sky. Grain has kind of a beautiful supplemental pattern to it rather than digital pixels. I was able to add the quality that film has onto the images, which I find really pleasing to my eye.

It was immensely liberating. I definitely would do it again. If I have more money, I'll probably shoot in super 16, which is a medium I really love. We shot a lot of films on super 16 or 60 millimeter, which has a very interesting, high contrast, high grain quality to it. But in the meantime, this is really liberating and inspiring. I think a lot of young filmmakers should really consider this option because the excuse is always they don't have the money, the wherewithal, they can't get the equipment– but if you can just shoot with a phone and you can shoot a narrative story, it makes it accessible so you can actually work, instead of talking about work and constantly trying to raise money for work. It was liberating and really radical in my life as a filmmaker to discover the ability to work in this medium.

Alexandra Kosloski: That's interesting. I think that a lot of the time, when there's constraints on something, it makes you more creative, trying new techniques that maybe you wouldn't have otherwise.

Alexandre Rockwell and Melanie Akoka on the set of Sweet Thing

Alexandre Rockwell: That's very perceptive of you. I think it's true. Constraints are what make it human. Sometimes a filmmaker will have no constraints and be able to manufacture perfect images, where the beauty of being human is the struggle- the struggle to try to make something beautiful with just a limited means.

Alexandra Kosloski: Could you share some of the inspiration behind the writing process of Lump?

Alexandre Rockwell: Yeah, it's funny making films; the more I do it, the more I realize that it's much more like music. Music is emotion, that's how you engage in it. It's a rhythm and it affects you. It almost goes past your intellect and into your soul, and film, I feel, is very much like that. It's not really based upon an idea as much as an emotional response to something. When I write, I try to write very, very fast and very direct because I feel that the interpretation of the story makes the story powerful. It's like the painter Willem de Kooning said, "Any idea is as good as another in art".

I think sometimes the more simple the idea, the more you can infuse your emotion into it as an artist. Which kind of gets back to what you said about limitations– they're there for you to simplify your work. You have less options so you channel your energy into this one thing.

So, originally the story of Lump was going to be episodic. I was going to do a web series based on two guys who work for a private eye. They have no idea why they're following somebody; they just know that they have to. I found really funny situations. The older Italian guy who plays the lead in Lump, Steven Randazzo, this is what he would do when he was supporting himself as an actor. He would get assigned to follow somebody and get paid $100 in cash. So he had all these funny stories. Was he following a hit man? Was it the husband from a jealous wife? And he never knew. One minute he thought he might be getting killed, and the next minute there was some poor guy who would just start crying in a bar. He would want to put his arm around him and say, "Look, I understand." He told me these stories so I just kind of jotted some of them down. I changed them a lot, but I just wanted to do these episodes about each person they follow. Then I realized there was a narrative film that grew out of it, so I made a feature.

Lump, 2024

Alexandra Kosloski: I love that that's coming from a personal experience. It doesn't feel fantastical or super idealized. Similarly, you said before that In the Soup was somewhat autobiographical, as well.

Alexandre Rockwell: A very similar genesis of the story. In fact, my movie, Sweet Thing, which my two kids are in is similar, too. I seem to start from a place of autobiography. I didn't used to, but then I realized that I tell stories about my life. Like when I was a young man, I was trying to make a film way back when, and I met a gangster. This guy really believed in me. We really wanted to do something which he considered important, other than just selling drugs and going to prison or whatever the hell he was doing. He saw me as a young guy who was full of dreams and he wanted to support me and see where it went.

I would tell these stories to people who were at my job– I was working all these crazy jobs, bussing tables, cleaning basements. I was always broke and telling my coworkers these stories about meeting this drug dealer who wanted to make films with me, and they would laugh. But I was dying, I was about to be murdered any minute because his brother was a homicidal maniac. So eventually I just started writing down some of the stories, and that's how In The Soup was born.

In The Soup, 1992

Alexandra Kosloski: What attracts you to these kinds of offbeat stories?

Alexandre Rockwell: I think all my life I've really seen myself as an outsider. I wasn't great at school, my parents are divorced, I lived on my mother's couch for a long time, and I never participated in a kind of a regular system of life. I didn't go to film school. I always found myself by meeting people and vibing off them. I went to Paris for a couple of years, and I studied. I was going to be a painter. I got jobs there. My life story drew me to outsiders as well. When I look back on my films, it's almost like I'm trying to make a community. Like if you notice the end of Lump, they're all sitting, having a barbecue– all these very disparate men. They were lonely once. All of these lonely people come together for a birthday party at the end. And that's how the movie ends with this kind of Cassavetes-inspired getting together to make a family. I've always done that. I mean, the same thing with In The Soup, I seem to be drawn by people who are outsiders coming together, forming a community or a family of some kind.

Little Feet, 2013

Alexandra Kosloski: That just made me a little emotional.

Alexandre Rockwell: I know it's funny. Like when I was a kid, I loved The Wizard of Oz. I just loved to watch that. I just love the fact that these weird people like the lion, the scarecrow, the tin man, they all came together and they form this little troupe of outsiders.

Alexandra Kosloski: That's something I can really empathize with– feeling like an outsider and looking for connection.

Alexandre Rockwell: I was jealous of Italian-Americans or people from ethnic neighborhoods when I grew up because they always have an identity. I always felt envious or jealous of that kind of thing. I realized my real community is outsiders.

I feel that outsiders, artists, people who live alternative lives, we come together and really appreciate the people you join with. You're not just choosing them because they're your family or they grew up down the street. You're choosing them because they see you for who you actually are. You're not just a conformist who's fitting into something, they actually see you. I think it's quite a beautiful thing. So later in life, I realized that's what I've always been trying to do. When I was younger, I was a little more insecure, but now that I'm older, I can feel that that's a really powerful thing in me, and that's something that I gravitate toward.

Alexandra Kosloski: Filmmaking is very collaborative. What are the challenges of manifesting your one vision with other people and so many moving parts? I imagine there's a lot of trust you have to have.

Alexandre Rockwell: It's almost like the best collaborators are the people who were given very clear goals. Young filmmakers often misunderstand collaboration, they think that we'll all make a decision together, like a democracy. Vote for this or that. Actually, my collaborators– musicians, or cinematographers, or actors– really want a clear direction. They want to hear your vision and they get very clear direction from you. Once again, you get better at it the more you do it, but it does present challenges. The one thing a director really needs to do is communicate. Each person is different. Some people need you to speak to them all the time and appeal to their intellect. Some people need to be left alone or encouraged. You have to orchestrate the whole thing. And casting the crew is just as important as casting the actors, because the vibe has to be right. People have to get along and be working toward the same goal.

Little Feet, 2013

Alexandra Kosloski: Who have you worked with that you've admired the most?

Alexandre Rockwell: I admire different people for different reasons. I admire Steve Buscemi a lot. I'm very close to Steve. I'm kind of constantly surprised by his ability, what he can do. I mean, he's effortlessly humorous. He can make you laugh doing anything. I could drive across the country with him and just laugh the whole time. Yet at the same time, he's a really well trained actor, and I don't think I completely appreciated that until I saw the work that he did with other people, because I didn't know he could do that. He just showed me so many colors. And there's something about Steve that I admire greatly as a human being; he's the most understated, un-Hollywood, unpretentious kind of person you'd ever meet. He's a real down to earth guy. I'm sure you've heard stories about him being a fireman, but on September 11th, he just walked up and helped take bodies out of the ashes without any publicity or anything. That's just who he is. He's as much a fireman as he is an actor. He's just a great guy.

I love Will Patton. I worked with him on Sweet thing. I admired him so much. I like to work with non-actors a lot, and he's trained in theater, television and film and can be in a scene with a non-actor and help guide him. I'm just completely blown away by how someone can stay in the moment and still work with a non-actor who is lost and can bring them back.

Alexandra Kosloski: I've seen Patton's work, he's excellent, and Steve Buscemi is just so beloved.

Alexandre Rockwell: He's the best. I've always known him as my friend, and he still is my friend, but I realized stepping away from it, that he's become somebody who you cannot replace. If Steve's going to play a part, no one else could play that part. And if they did, it would just be a completely different part.

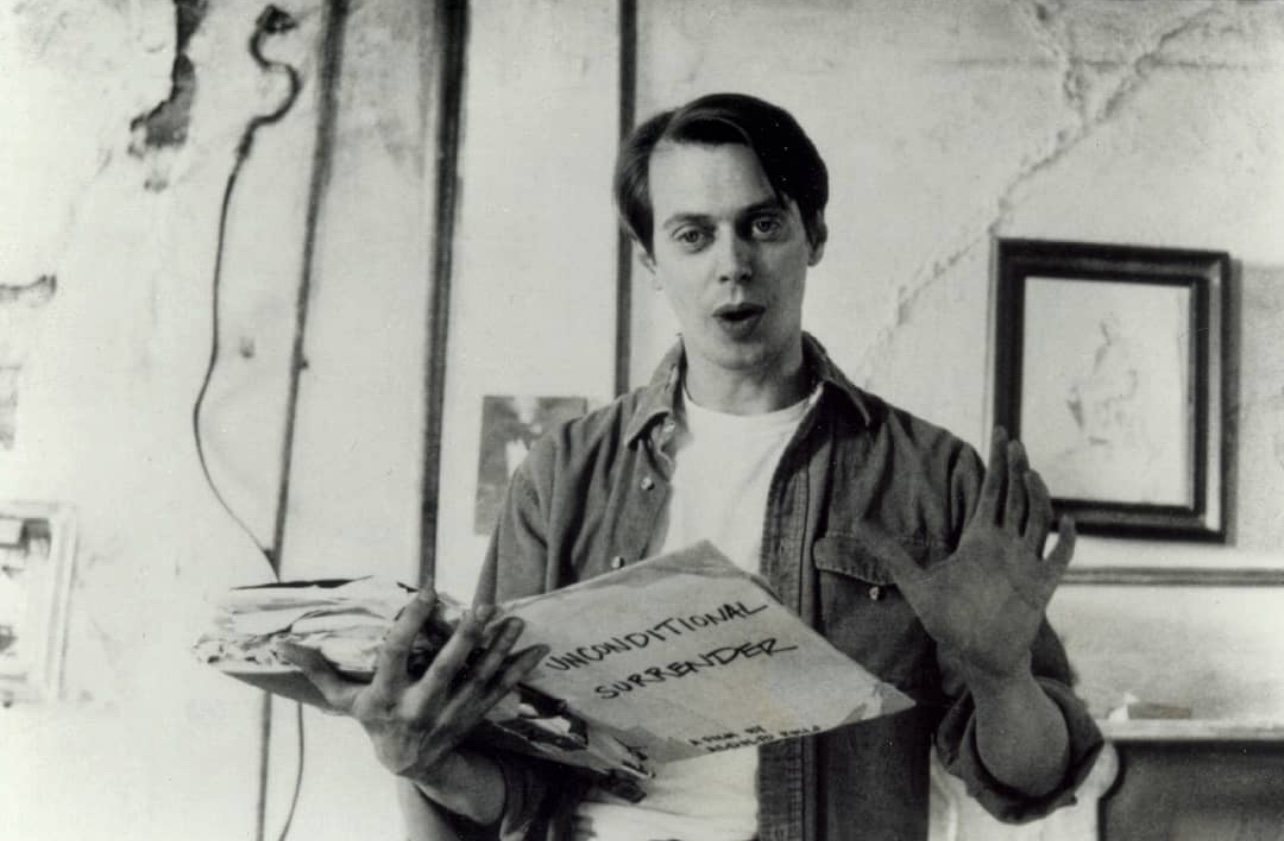

Steve Buscemi in In The Soup, 1992

Alexandra Kosloski: Could you share a moment in your career where you were challenged creatively, and how that turned out?

Alexandre Rockwell: Yeah, I had several moments. Multitudes. Probably even today I had a moment. A more severe moment where I was challenged is when I was in Hollywood. I was trying to make films and I just had two kids, and I was going broke. It just felt like I was becoming a professional loser, trying to get money for films everywhere I went. The most difficult part of it was that filmmaking, the one thing that worked for me in life, was starting to take a really bad turn. I didn't like it. I didn't like trying to go meet people to raise money. I didn't like going out to dinner with people who I couldn't stand, just trying to charm them into giving me money to make a movie. I didn't know if I was a filmmaker anymore. I kind of had a crisis.

I had a Bolex camera that I had since I was 18 to make my first films on, and I said, okay, I got this camera, I've got these two incredible kids. I'm going to go get some film, and I'm just going. I used to write in a restaurant. I remember talking to the busboy, "What do you do?" And he said, "I'm an actor". And I asked him if he would want to work on a film and if he would do sound. He said, "Sure, but I don't know how." I said "Don't worry, I'll teach you in an hour how to do sound." I met the guy who shot the film in a playground. He was pushing his kid on a swing, and he was a cinematographer. I hired him to shoot the film. And so we shot on my Bolex with my kids, and it was this movie called Little Feet. I made the movie for almost no money, and I rediscovered what I loved again.

Going back with the limitations– I had nothing but this camera, my kids, and three people working on the film. I was going "God, I love this." I was working in the medium that I know how to work in, and I loved it. So I made this little movie called Little Feet. It was really well received, got great reviews, it even came out theatrically, and I was really pleased. It reinvigorated me. It sounds like a self-help kind of thing, but it's really true– in the moment of crisis for anybody, the kernel of some incredible gift is right there. In crisis, something's being offered to you, and you either take the challenge or you don't. And I guess when I made Little Feet, I did take the challenge and it gave me everything back.

Alexandra Kosloski: There are times where you just lose control a little bit, but that'll bring you to something unexpected.

Alexandre Rockwell: Yeah, it's scary, of course, because it's like you're jumping into a void. You're worried, but you have to have some faith. When you lose everything, it's much easier to see what will pull you out of it. In fact, I've seen a lot of very unhappy people who actually are getting what they want– like they're getting films made, they're getting money, life is giving them everything they're asking for. I'm not saying in all cases, but in a lot of cases, people lose their rudder and they're not connected to it anymore.

Alexandra Kosloski: So, themes that I see in your work are, first, youth and innocence– of people facing a world and not understanding it– and also some kind of intimacy. I feel like that makes them more relatable in a way, it's something very personal.

Little Feet, 2013

Alexandre Rockwell: When I show my movie to audiences, even like when you were in that screening the other day, generally speaking, people come out and really moved. I've had people crying or laughing at the end of my movies. It's like they're connecting to something intimate, like you said. I think that's what it is.

Youth definitely is part of it, but I think even more than youth, it's innocence. I think there's something about vulnerability and keeping a childlike view of things. I mean that in the highest respect– to go into a situation and be open to being vulnerable. And sometimes, people coming together from very different places creates that insecurity that can make you vulnerable. It can create a clash. In the case of Lump, you have a wounded older man who's kind of shut the door on life. One of my friends, a French filmmaker, says it's like he starts off in a coffin and at the end he's celebrating his birthday. He meets this innocent person, this man who fell to earth. He's full of hope and faith and innocence who pulls this guy out of his shell. So, yeah, all those things are perceptive.

I guess that's sort of my cross that I carry, because I think we're living in cynical times and I think that intimate films show vulnerability– I'm not saying it's people who aren't interested in that, but a sign of our times is anger or resentment. I am more into vulnerability and openness.

Rockwell and Buscemi at the Lump post screening Q&A

Alexandra Kosloski: I could see this manifest technically too, because since Lump was often shot in a car, there were a lot of very close shots. It was right in their face. I felt like I could smell them. The sound also really intentionally brought so much to the film, and I think that activated these other senses and made the film feel so visceral.

Alexandre Rockwell: That was a real advantage to being inside the car with the iPhone. When you're shooting in a car, usually you have this large camera and you have to shoot through windows or tow the car, whereas in this movie, they're really driving. We were able to move the camera around as if we're in a football field, but we're inside a car. That was a real benefit to the iPhone.

You know, it's interesting getting the camera close to people because in other movies of mine I haven't done it as much. I think you have to be careful. It's a very delicate thing because you don't want to invade someone's privacy. You want to allow them to retain their dignity and their own sense of self. And so that's another thing that the iPhone does well– a big camera will frighten them away, but we're so used to looking into the phone that you can bring the phone in and not make someone as self-conscious. They can stop being so aware of it so that intimacy can come out.

Alexandra Kosloski: Can you share any behind the scenes stories from filming Lump?

Alexandre Rockwell: I can tell you a funny one. We shot often without going to the trouble of getting permits. So, we went to a movie theater and I wanted the guy who played the panda man, M.L., to take off his clothes and have a meltdown in front of the mirror in this public bathroom. And, so I tried to find a public bathroom where it would be pretty empty, and I rigged up a thing where someone was outside the bathroom with a telephone and I said, if anyone starts to come towards the bathroom, call us, because this is a little intense. I got this guy screaming, staring in a mirror naked. You know, this could be a problem.

So, we were filming, he took off his clothes, and all of a sudden I got a call that there was a kid coming in the bathroom. We had like three seconds so he ran naked into a stall, and I was in one stall, Stephen and Jocar were in one. The kid went into the last stall and we all tried to hold our breath. We're obviously in there. Then the father followed the kid in and was standing outside the stall. We're just holding our breath. The guy goes out and the kid leaves and now's the time for M.L. to scream. And he's fantastic, he doesn't give a shit. He's just doing everything for the movie. So he does it and we get it, and he puts his clothes on and we leave. And just as I'm walking out of the cinema, I can see the security and two police officers heading toward the bathroom, and we just barely slipped out.

We had all these crazy stories, like going in and shooting in a Chinese restaurant. I just told them we're shooting a birthday party. We did all the lines and we had to keep reshooting and I think they got wise to it after a while, but they let us shoot there for nothing. Every day was a new crazy, wild adventure

Alexandre Rockwell and Lana Rockwell on the set of Sweet Thing

Alexandra Kosloski: That's the exciting thing about independent filmmaking is that those risks can be taken. And yeah, ML was great. He came off so uninhibited, so natural.

Alexandre Rockwell: He's such a great guy. I've worked with him in Lump and Sweet Thing. He's just so willing and so hungry. I love working with actors like that. I totally understand why some actors don't want to do that, but I love working with actors who just do whatever it takes to get the performance, because that's what I'm like as a filmmaker. I love it when no one's holding me back. You never want to take risks with health or an injury or something like that, but you definitely want to take emotional risks and, you know, some legal risks.

Alexandra Kosloski: I feel like it enables you to put the storytelling first and all the technical things come after.

Alexandre Rockwell: There can't be art without risk. You get so many great things when you lose control. And yet you're shaping it, you're sculpting it– it's wild. It's like dealing with fire or water, it's like you're trying to channel it.

Sweet Thing, 2020