“No one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge.”

-CG Jung

Continued from Part 1

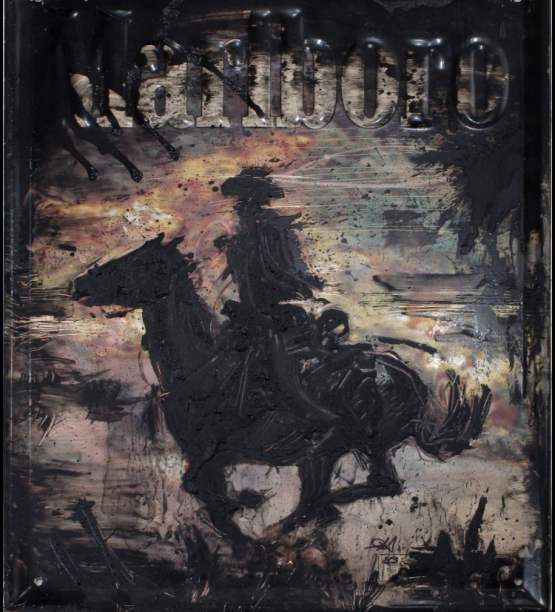

The only thing “street” about Hambleton was that his first works in New York City happened to have been painted on public property, the DOA series conceived directly on the sidewalks and asphalt, then the painterly shadow men that would make his bones as a living legend. Unlike the aforementioned artists who premiered in the trenches alongside the roguish graffiti demi-monde, Hambleton’s shadows painted on the wall did not need to be painted on the wall to be transformed into Art in context, and neither was there any entropy in the eventual transplanting thereof onto canvas, to hang in some white box with the grandeur of crown jewels. Anyone with a modicum of knowledge of Art History could draw a line directly from Monet’s splattered Water Lilies, Picasso’s expressive contortions, Pollock’s liberated unconscious arabesques, straight through Richard Hambleton’s punk rock sprezzatura sensibilities.

Very quickly Richard enjoyed a caliber of celebrity that elevated him above the fray, positioning him alongside Schnabel and Clemente, with his sold out shows and matinee idol good looks. When at last I identified the Shadow Man in a photograph, it was not from a mug shot. Here he was posing in a glossy magazine spread, the cultural ambassador for the jet set throwing paint like Yves Klein, and finally putting a glamorous face to the name, most incongruous to the terrifying images he left behind on rat-infested squatter tenements.

Richard Hambleton

5 ShadowMen

Warhol died. Basquiat died. Haring died. Hambleton fell from the ivory tower. The party was over. New faces filled the magazines. Then dad came home with a crazy story. He was digging a Jazz ensemble in Tompkins Sq Park when a wild man approached on a rickety bicycle and offered to sell him a painting for fifty bucks.

At first he had been a phantom, then a movie star, but now he was a blood and guts Bohemian, struggling with a bad habit, and just like the cowboy clinging to the reigns of a violently bucking bronco in the painting my father purchased, he was fighting for his very existence. A vulnerable human being, and a fast family friend. Little by little our house filled up with the Shadow Man’s handiwork. He was short on rent, he needed a small loan, the calls came in at odd hours. He’d emerge out of a waiting taxi, leather jacket cinched shut with a jumbo paper clip and a wild look in his eyes, and then in the living room sprung up a figure frozen in the act of leaping into the air like Nijinsky or Michael Jordan, hair standing up straight as though electrocuted.

Richard Hambleton

Horse and Rider

Pops rented a studio for him in Astoria. Against my will I joined the visit. Richard had reams of canvas stretched across the wall and painted mobs of Shadow Men standing shoulder to shoulder in volatile confrontation, hemorrhaging energy and crazy ideas in gobs of gooey black, horses rearing up, thrashing blindly to throw their rider, at last, into the dirt, dramatic as any Tyson fight, as Richard dashed across the studio, a one-man rodeo, flinging paint-caked brushes, unrolling last night’s work painted with the vivid intensity of a fever dream. Maybe I had feared that he was taking advantage of my Dad, but now I too fell under his spell.

Which of us was not scared of the dark as a child? And how much does it mean to us when some cowboy looks evil in the eye, stands up to a fear of the unknown, that darkness that dwells in all of us we somehow never get around to confronting? It is there looming in Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, in the moody Venetians, in Rembrandt’s inky umbers, in a tonal late Rothko, heaving like the sea by night, embodying the fears and doubts we all contend with beneath the surface, that the occasional Ahab rises to the helm to reckon with in our place, and for the greater good of humanity.

Richard Hambleton

Seascape

I found time to visit Richard on my own now. He had been living in some former auto repair garage, slept in a dentist chair, with a television jury rigged to be lowered on a chain by a lever whenever he laid down. One summer night we ventured outside and painted on the streets together with Omni and Lola Schnabel. Things we never photographed, never yearned to be seen, much less sold, but painted for the sheer joy of invention.

Pops set up an exhibit for him in some gallery uptown off Madison. Maybe the horse and riders would not stand still for a moment, nor the rhapsodic brushwork they were comprised of, but as we installed, now I had occasion to sit with these works for a contemplative moment. My father shared the observation that Pollock had died in a failed effort to return to the figure after spearheading a nonrepresentational revolution, and it was Hambleton who rather carried this aim to its conclusion. In the most carefree way, Richard could articulate a horse’s anatomy as meticulously as George Stubbs, but that blurred streak of a rider was hardly even a human any more, obliterated by the storm-clouds and dust storms of unruly activity.

Continue to Part 3