John Newsom, Keep Watch, 2020. Credit: Oklahoma Contemporary Museum

Combining realistic representations of animals and vegetation, Abstract Expressionism, and hard-edge geometry, John Newsom’s paintings explore our intricate and complicated relationship with nature. I spoke with John about his origins, his practice, and his upcoming exhibitions – a mid-career retrospective at the Oklahoma Contemporary Museum and a two-person show with Raymond Pettibon in Palm Beach.

Continued from Part 1

JN: I grew up in a very solid family structure and being very close with my family. I have a family now and I just love family. I'm crazy about my family. So a strange thing happened on my 14th birthday. I thought that everybody had forgotten my birthday. Like everybody was playing dumb, they didn't acknowledge it. And it freaked me out. It was a problem.

I went up to my room and was just kind of sad about it. It was on a Saturday. My Dad came up, and he peeked in and he said, “Hey, you want to drive downtown and get a Coke?” I said okay. And so we drove downtown. It was a beautiful sunny day. It was like a Norman Rockwell painting. We went into this soda stand and got Coke floats. We were talking about baseball and things like that. And then he said, “do you want to take a drive to Oklahoma City?” And I was like, yeah, sure, why not? I mean, that wasn't totally out of the ordinary, but it was cool that he said that. But still no mention of the birthday.

Downtown Oklahoma City, 1987

So my dad and I drove to Oklahoma City. And at the time – this was before the ages of heightened security and terrorist alerts and all that – you could literally drive up to the tarmac of the landing pad at the airport, which is what we did. There was a small commuter plane waiting for us on the tarmac. I mean, it wasn't a private jet or anything like that. It was just a small plane, which was cool. My dad looked at me and he said, “Hey, you want to take a plane ride?” Now this had never happened before. This was different. But he got up, we got on the plane and I was excited. I was just thrilled. This was an adventure.

We took off, I didn't know where we were going. We were up in the air for a little over an hour, I'd say an hour and a half. We started making our descent and I look over and there are buildings around. We’re landing in a city. The plane lands, and we get out and there's a car waiting for us. Not with a driver or anything fancy. It wasn't anything fancy, but it was everything to me. This was the moment. My dad’s like, “Hey, you want to take a drive and see where we're at?” It was amazing how he laid this out. So we get in the car and we start looping around and we are in heavy urban traffic and it's going fast. It's moving. It's not stalled. It's not like being in LA during rush hour. It's fast-moving and we zoom off the freeway and I'm just wide-eyed looking out the window. The car stops. I look over at my dad and he puts his arm around me. He looks at me and he goes, “Happy Birthday.” Oh my God. And I look out the window and it says the Dallas Museum of Art. I blew open the door. There was a sidewalk, a long sidewalk between the car and the front door. And I just started running down the sidewalk, and there's this giant leaning wall of steel on the left side of the sidewalk. And later in life, I would tell Richard Serra this story – I literally did that, Nathalie. I told him this story. I actually got him to smile. It was its own achievement, but that's for another time.

NM: I'm smiling just hearing this.

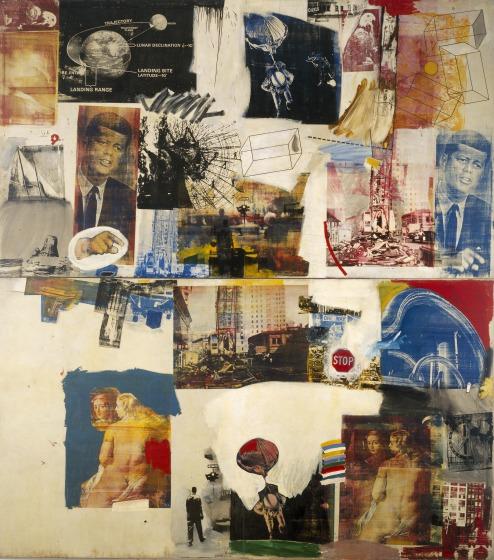

JN: Yeah, man. But I didn’t know what it was at the time. I had no idea. All I could do was read the sign, Dallas Museum of Art. I run to the door. I walk in and I didn't need to do check-in right away or any of that stuff – again, I was just 14 that day. So my dad was going to handle it. Because – because – installed right in front of me on the main wall was Robert Rauschenberg's largest Combine Painting, Skyway, from 1964. And I just had an epiphany. John F. Kennedy was pointing down at me and I just saw my life flash before my eyes. I heard the calling. I was like, I'm going to be a painter. For real, for real, I'm going to go all the way with this, whatever that means.

Robert Rauschenberg, Skyway, 1964. Credit: Dallas Museum of Art

NM: Yeah, you flipped the switch.

JN: I really didn't know what that meant, but I knew that it was happening. I knew this is what I wanted to do. So that was real, the real root of it. We had a great time. My dad came in, bless his heart, he didn't know what was going on. He didn't know what he was looking at.

NM: I have the same experience with my dad to this day. He always asks me to explain it to him, what does this mean, what am I looking at, you know, and I’m like, Dad, that’s beside the point.

JN: Right, he didn't know, but thank God I had supportive, loving parents because they passed it on to me and I support my children like that. That's a healthy chain of events, so that's very cool beyond this discussion. So he walked in and he said, can you explain this to me? And I start talking about collage and painting, and there's a giant Claes Oldenburg rope, anchor sculpture thing that's extending from the ceiling down to the floor. There was a Jim Dine painting that has collaged tools in it, spray-painted elements, and just all this radical stuff. It was a radical presentation of Pop Art. It wasn’t so smooth. Even the Lichtenstein – it was the painted ceramic female bust. It wasn't a domestic item. It was romantic, it was interesting, it was great. It was colorful. It was very tactile. I loved it.

But the Rauschenberg was the win for me that day. It really was, and I was kind of veering off the initial discovery of this whole thing via Warhol. I mean, I still love it. I admire it. I never got to meet him, but I hold his work in reverence. But just through self-discovery in life and your own painting practice, you come into your own. So I was, even then, veering away into other things, but I still was hoping to see a piece because I had never seen a Warhol in the flesh. But it wasn't in the main gallery. So we walked through all this stuff, and before we left, I asked the person at the front desk where the restrooms were. I go to the restrooms, and there in between the restroom doors were two Warhol electric chair paintings. I was like, there they are! There they are. For some reason, they didn't hang them in the main gallery. But if I hadn't asked to go to the bathroom, I would’ve never seen the Warhol paintings. So I got to see them. They were really cool because those were some really edgy pieces. The electric chair series is just so intense, and I've seen thousands of Warhol paintings since then, but those are some of the best.

Andy Warhol, Electric Chair (Portfolio), 1971. Credit: Dallas Museum of Art

The Dallas Museum of Art is amazing. I saw a Philip Guston retrospective there. It's a great space. I came back to Enid, the small town where I was from in Oklahoma, and my life would never be the same. I started taking pieces of found wood and plywood panels and I would staple TV dinner trays to the pieces of wood and throw paint all over them and take them into my art class, present them as art, and everyone thought I was crazy. Because that's what I really wanted to be doing. But on the other hand, I was trying to draw as realistic as possible because that's what everybody was getting off on. It was like, wow this guy can draw like the wind, it's amazing, it looks like a photograph – but then I'm doing this crazy, really tactile, abject painting. I was just getting into it, you know, I had all this passion, but not really much direction. I was swirling and I continued to swirl for the next two years, which was good. It was all build up. I was still going to the library in my teenage years and I discovered an area of magazines that they had. I wondered if they had a magazine for art. So I asked the librarian about it and sure enough they carried ARTnews magazine.

I got a copy of ARTnews… and it was a still a little early, maybe late 13, 14 years old. I got back from Dallas and I was like, I gotta keep figuring this out, and we didn't have Google. So I found ARTnews and I started reading it and I waited and anticipated when the library would get the new issue. I would look at the ads and I would read the reviews and articles and I'd discover artists. That was my junior high school into high school education of art. I knew what the galleries were showing in New York when I was 14, 15 growing up in Oklahoma. And honestly, Nathalie, I couldn't wait to get there, because we had taken a family trip to New York around that time as well. I told my mother, I said, “this is where I'm going to live.” She was like, oh John, okay, whatever, and I’m like, no – mark my words. I'm going to do this. I'm a Taurus. So once I set my mind to it, it’s happening.

Julian Schnabel on the cover of ARTnews, April 1985

JN: So I found an ad in the back of ARTnews. It was a quarter-page ad for a summer camp called Interlochen in Northern Michigan, outside of Traverse City. It was advertised as a music camp, and I thought that was interesting, but I also read that they had painting. It was music, dance, and painting. It was basically an art preparatory school but a summer camp, and everybody was going to camp, including myself. I'd gone to baseball camp and church camp, but I didn't want to go to those camps. I wanted to go to art camp. So I asked my parents, I showed them the ad and I said, “Hey, what do you think about this? This sounds really amazing. Can I apply?” Everybody was going to camp, so they were like, “well let's see.” We looked into it and long story short, I got to go to the summer camp Interlochen.

That was kind of another pivotal point in this process because I just fell in love with it. It was just fantastic because there were instructors there, it was serious. It was life-drawing and still-life drawing and blind contour drawing and printmaking and introduction to woodcutting and intaglio etching. It's all that stuff, you know, the classics. It was the academy. So while I was there, I discovered that they did offer the academy during the school year. I couldn’t go back home. I thought, how am I going to get to New York if I don't do this? I don't know how, but this is part of my journey. So I went, I left in the middle of high school to go to Interlochen Arts Academy. I got in and I worked really hard and I loved it. And it was just everything. It was –

NM: Where you needed to be.

JN: Nathalie, it was just everything. It was just amazing. I dove into art history and the hardcore academics of art-making and the instructors were incredible. They were also interested in regional exhibitions that were happening in places like the Detroit Museum and Cranbrook and we would take trips there. I remember going to the Detroit Museum one time and they had a giant Rosenquist painting. I think maybe it's where I grew up because I did grow up with a horizontal landscape, whereas my kids are growing up with a vertical landscape because they live in the city. It's just a different site point, it really is. Day after day you get accustomed to it. So there really was an expansive field to the things, or paintings, physically, that I was attracted to. Just the scale of it. They’re like grand spaces you can walk in. If you get far back enough, it becomes another picture, you get close, it becomes an incredible physical reality. It's just an amazing thing. So Rosenquist, how he was using aspects of visual collage was really interesting to me, especially the idea of remixing – again, revisiting notions of MTV and early days of Hip Hop. Even like certain types of rhythmic or electric guitars, metal, Kraftwerk, anything, listening to all this stuff. I'm thinking, like –

James Rosenquist, Star Thief, 1980

NM: Thinking what is going on!

JN: Yeah! Thinking that this is our time. This is now, it can't be like the Italian Renaissance. It’s different, but you got to go and learn all that stuff. You asked me in the beginning about school and things like that. I really felt obligated to go in and learn as much as I could and just figure out the etymology of what it was I was getting involved with. And I love it to this day, I love just sitting down and getting into it like that. Doesn't have to be about my own work. It can be about ideas of artistic thought and movement and other things. You know what I mean?

NM: Absolutely, I totally agree.

JN: So that was a really great period of work and development for me. And then the time came to leave and I applied to The Rhode Island School of Design and Cooper Union, and I got into both, but I decided to go to The Rhode Island School of Design. I applied there first, I got into Cooper after RISD and I just thought it would be a little buffer before New York, let's put it that way. Being a late teenager, New York might've been a little much, but I knew I was going to be there eventually anyway, so it didn't matter. So I went to Providence. It's a gorgeous city. It's a very, very European city. I felt a little stunted to be honest, the first two years there, and I came very close to transferring to Cooper Union.

NM: And you were in the painting program at RISD?

JN: Yeah, I was in the painting program. I was just ready to get to New York, but I still wanted to be in school. It just wasn't time yet. But then I started to meet some people. I started to make some real friendships and I stayed there. I didn't go. I finished at RISD and then I came to New York in 1992. So I've been here 30 years now. Then we get into New York itself, but I mean, we just covered a large swath of my history from the beginning to New York. Those are key points, the highlights.

John Newsom in his Spring Street Studio, New York, New York, 1992-93

Combining realistic representations of animals and vegetation, Abstract Expressionism, and hard-edge geometry, John Newsom’s paintings explore our intricate and complicated relationship with nature. I spoke with John about his origins, his practice, and his upcoming exhibitions – a mid-career retrospective at the Oklahoma Contemporary Museum and a two-person show with Raymond Pettibon in Palm Beach.

Continued in Part 3