An Interview with Nemo Librizzi

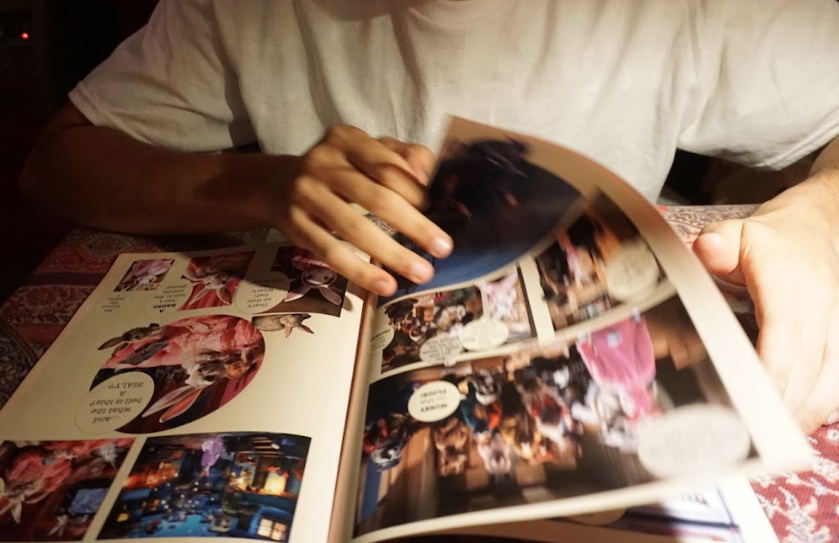

Nory Aronfeld and “So Bad It’s Good” by Nemo Librizzi, photo by Bebe Uddin

In his interview with Alexandra Kosloski, Nemo Librizzi shares the essence of bohemianism, emphasizing the intrinsic drive to create art regardless of external validation. From his graffiti roots in New York to using AI in illustrating his graphic novel “So Bad, It’s Good,” Librizzi discusses his artistic evolution and ongoing projects.

Alexandra Kosloski: What does it mean to you to be bohemian?

Nemo Librizzi: Well, sometimes the arts equate a livelihood. Art can make some people very wealthy, and some people it even makes famous. But for anybody who has ever made something– before there was ever any question of an audience, you’re making it for yourself responding to some unsettled feeling or raw urge to create.

Some people make beautiful things because they came up in an environment of beauty and elegance, and others come from a very dysfunctional place, and have a vision of a more beautiful world. There are people from all walks of life that find themselves in a position to create something. To make something becomes more important than practical realities. People who make art even though they’re not understood or can’t make ends meet by this pursuit, and they do it anyway, we call that a bohemian.

“I think that each of us has an inclination or sensibility to create based on a dream or a feeling.”

I think that each of us has an inclination or sensibility to create based on a dream or a feeling. Not everybody tries it, and out of the people who act on this fantasy, not everybody strikes a chord to be readily understood by others. In which case, the realization is still useful to oneself. Art for art’s sake. And in our society, there are these cultural specializations: you’re a lawyer, you’re a doctor, you’re a statesman or something, or you’re an artist. In other cultures, perhaps it’s more acceptable to be a Renaissance person. You make something, but you also have a regular job, and it’s not necessarily merely a hobby either. It’s part of who you are- a more nuanced part of your identity.

Alexandra Kosloski: I would say that you’re a pretty good example of a Renaissance person. You seem to be an artistic shapeshifter. Can you share a little about your journey from graffiti art to filmmaking and beyond? How did your experiences influence this artistic evolution?

Nemo Librizzi at the launch of “So Bad It’s Good (Part One)” at Village Works

My dad was a painter his whole life, and a poet, although he was an art dealer by day. Just being with my dad as an art dealer, we used to go to Warhol’s Factory, or Tom Wesselmann’s studio, or different artists ranging from the abstract to photorealist. There were no hard and fast rules for my father about what constitutes art other than it’s a movement of the soul.

So when graffiti came around, I remember seeing it on the subway and asking my dad what it was, and he said, “The kids go in the tunnels at night and do it.” I must have been 5 or 6 years old. I told my dad, “I want to do that”. He said, “You have to practice and when you get bigger you can go do it.” And I did.

I focused on it for many years until I went and painted on the subway. The first time I did it was ’82, maybe ’83, and I wrote all the way up until they phased out the graffiti trains in around ’88 or ’89. It was a starting point for me because at that moment when I was initiated as a graffiti artist, it came in vogue in creative circles that people from other disciplines were paying attention to what was happening on the streets in New York. So I found myself, as a graffiti artist, part of this inner circle of people like Jean-Michel Basquiat or Keith Haring or Martin Wong, because all these people were interfacing with that street avantgarde. And I never saw a clear delineation between the different arts. I felt they were all equally relevant.

Sometimes I get an idea that might be musical in nature, and I have to try to figure out a way to make a sound that echoes the sound I’m hearing in my head. I used to make radio shows because I’ve never learned how to play an instrument. That’s just one facet of self-expression. But I also write books and make little films. I think you are inspired by a spark of an idea first, and then that idea knows what it wants to be. Maybe you need to learn some formal things, to bring it into fruition, but technique is not art. The technique is a means by which we express the idea that we have.

Alexandra Kosloski: I’ve experienced this. It feels like the idea is the one driving the car and you just have to be in the passenger seat.

Nemo Librizzi: Absolutely. You have to help it get where it’s going.

“With some Bohemian comrades-in-arms in 2009”

L to R: Ben Ruhe, Nemo Librizzi, Lance de Los Reyes, Kiernen Costello

Alexandra Kosloski: Do you have a favorite memory of when you were Style Writing?

Nemo Librizzi: I had that dream when I was young, but it’s not as simple as painting in a studio. It’s a fearsome thing when you’re nine or ten years old to actually get to a place where you can write on a train. The trains themselves are dangerous. You’re trespassing into subway property, where the people that work on the trains get killed while working there. So us as kids, you were taking your life in your hands. And on top of that, if you didn’t get arrested or hit by a train, the place was full of gangs that would try to steal your spray paint and beat you up. And if you had any kind of name, a sucker reputation could follow you around and ruin your chances of getting your name up.

There was a lot to contend with, especially being a white kid and the son of an art dealer. I wasn’t as tough as a lot of my counterparts. When I could finally paint the side of a train– objectively, my first efforts were horrible, looking back– but I was proudest of that moment where I first achieved it at last, because nobody handed me that victory. I went out and I made it happen just by my own backbone. Even though it wasn’t any great glory in anybody else’s eyes, I proved something to myself that day.

Young Nemo Librizzi in NYC

Alexandra Kosloski: Can you think of a time that another artist surprised you?

Nemo Librizzi: Oh, God. Artists always surprise me, so they never surprise me. I can give you three occasions. One was VFR, who’s a graffiti artist, and his specialty was “tagging”. His signatures were all over the city. VFR made a campaign to go all city [known for graffiti throughout all 5 boroughs of NYC] one of the highest ideals that a graffiti artist can realize, if you’re not going to concentrate on doing what we call “burners” [large, elaborate wall pieces]. When we first met, we were all selling fireworks down on Canal Street. My partner CHAMA saw talent in VFR that honestly, at that moment I felt was too raw. He was too young. But, at some point VFR matured. I don’t know what it was, but one day a light went on in his head. Suddenly he had one of the best signatures in the city and of all time. It shocked me to think the kid ended up being great.

I felt the same thing with the photographer, Khalik Allah. His videos for Wu Tang Clan seemed very straightforward, but he wasn’t coming from any poetic background that I recognized, he was pretty much self-taught. Somewhere along the line, he discovered these people on 125th and Lexington, who were smoking K2. K2 is supposed to be synthetic weed, but it takes people to a much more psychotic break with reality than marijuana takes somebody. Khalik Allah took it upon himself to document these outcasts, and it was like his soul was reaching out to theirs. These weren’t stars, or even conventionally “cool” people. Yet, there developed a very vital connection between the viewer and the subject. I think the resulting works are of great importance on the landscape of our city’s history.

The third example is Martin Wong, because Martin Wong used to hang around all the graffiti scenes, and he was a very self-effacing, humble guy. Although he dressed pretty outlandish and had a big, larger than life personality, he was very earnest. I never knew him to be an artist, I just knew him to be part of the underground. He was an enigmatic character.

And one day, I was brought to see his paintings. It was his Chinatown series, and I had my mind properly blown. Martin Wong was probably the biggest Trojan horse for me in that he had always been there. I was friends with him. I’d hang out and eat dinner with him and I never knew how great of an artist he was until very late in his life.

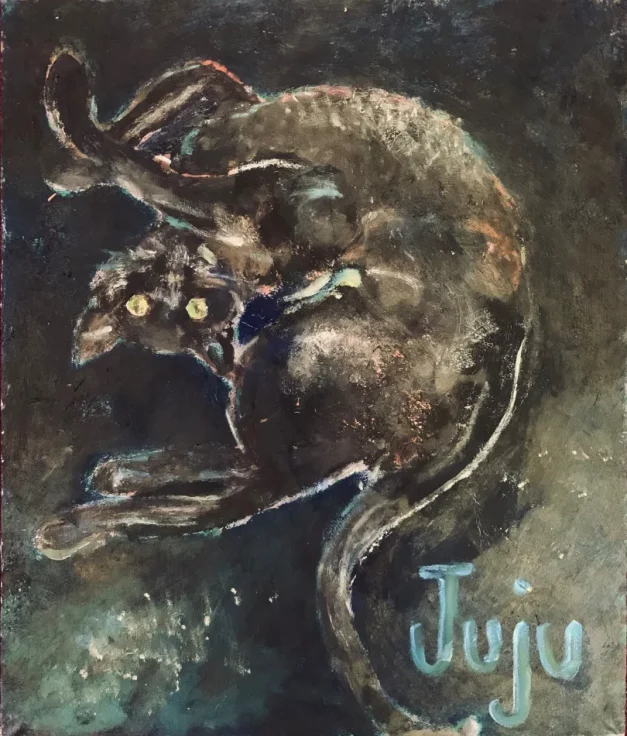

Nemo Librizzi, Juju, oil on canvas

Alexandra Kosloski: Who are your biggest influences?

Nemo Librizzi: I probably have a thousand biggest influences. I think that if I had to make a shortlist, though, they would probably be all of the outlaws, like John Genet and Caravaggio. Jack Black, obviously not the comedian, but the stickup guy who became a writer in the 1920s. Or Petronius Arbiter, who wrote the Satyricon. Or Eugène Sue. Rimbaud. Anybody that had an aptitude for culture and intellectual rigor, but was also there on the street corners where things actually happened. Henry Miller is one of them. Bukowski. We see this “terribilita” even in the Abstract Expressionists. We find it in Reggae and Dancehall and Rap music. Art that has blossomed right out of the mud of everyday human life has appealed to me most.

Alexandra Kosloski: The counterculture.

Nemo Librizzi: Yeah.

Alexandra Kosloski: I wanted to talk about “So Bad, It’s Good.” It brings a really unique approach to storytelling since it’s AI illustrated. What led you to this style?

Nemo Librizzi: I had written the play about 15 years ago, and it was my intention to have it acted on stage in costumes. I got kind of far along in the process where I was actually meeting with theater people, but it fell between the cracks. I didn’t know quite what to do with it, and I moved on to other endeavors. And then when I saw a friend playing around with AI, I was like, bingo! I can mine that source with this idea. I have chops as an illustrator, but I can’t compete with what AI can do on this level. I can fill up the pages with endless details. I think the AI has untold potential, though it’s unwieldy at times. It’s like trying to make a fine sculpture with a chainsaw, really, because it’s such a powerful tool. It can lead you by the nose if you’re not careful.

Alexandra Kosloski: What inspired the world of Norbert and the hijinx of Petropolis?

Nemo Librizzi and Ibrahim Kandji at the Trops launch of So Bad It’s Good (Part One) at Village Works in NYC

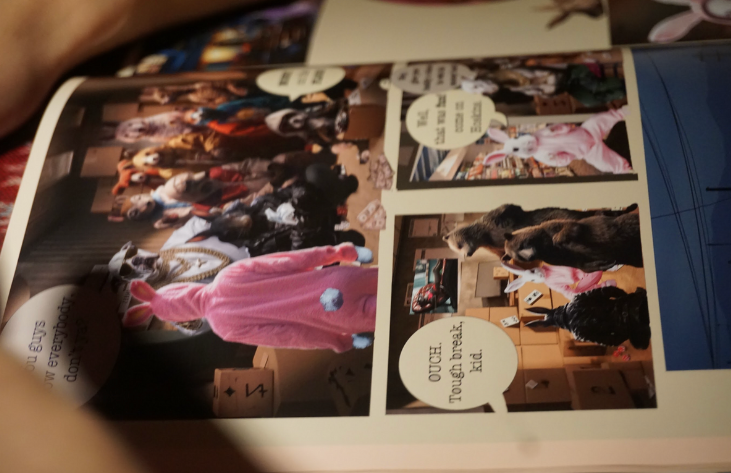

Nemo Librizzi: For many years I’d been a starving artist, I was happy to live wherever I could hang my hat, until I became a father for the first time. In a way, Norbert’s struggle is autobiographical– he has 14 or 18 kids, I have one to worry about– but suddenly I had somebody other than myself to worry about. When I started to face the problem of making a living, I realized, everybody faces those problems. I had to laugh at myself. Struggling to make a living is not really an epic human battle, it’s just normal. “The daily grind” most people call it. So it wouldn’t have been that funny if I wrote a play about my own mundane struggles, but now putting bunnies in there, trying to hustle their way out of an animal ghetto- that becomes funny.

We all grew up with some kind of fairy tales, and most of them were about little bunnies and puppies, with very little resemblance to our own world. They’re usually acting out some sort of moral maxim or ethical lessons to children. I tried to replicate the everyday realities that people are up against in the inner city, except enmeshed with a fairy tale or cartoon world. I just thought it was a funny juxtaposition that I’m sure other people have done, but that’s my own take on it.

“So Bad It’s Good” by Nemo Librizzi, photo by Bebe Uddin

I find it entertaining to immerse myself in the process of making it. It’s almost like playing with a dollhouse. It’s an escape. We got the second chapter at the printer now, I’m in the process of making the third one in the trilogy now. And my friends down here in Miami, tonight they’ll all be going to a party or something, but I’ll rush home to get working on this. It’s more exciting than being at a party. You never know who you’re even going to meet on AI. Once you type in the prompt, you see all these strange faces emerge out of the mist, and it’s just a fascinating process.

Alexandra Kosloski: Yeah, it brings some levity to the story. Besides part two and three of “So Bad It’s Good”, what are some other current projects that you’re excited about?

Nemo Librizzi: I started writing a novelization of Dirty Dancing. I was really excited about it at the beginning, and it wrote itself, but at some point I started struggling with it. I needed it to be a little bit more than a simple rehashing of the story. A filmmaker friend thought it could be cool for it to become a movie, then it could be Dirty Dancing- the movie based on a book, based on the film. It starts to become a hall of mirrors in that way. Other than that, I’ve been making some more little films for YouTube.

An Interview with Nemo Librizzi Read More »

Interview