An Interview with Sante D’Orazio (Part 3)

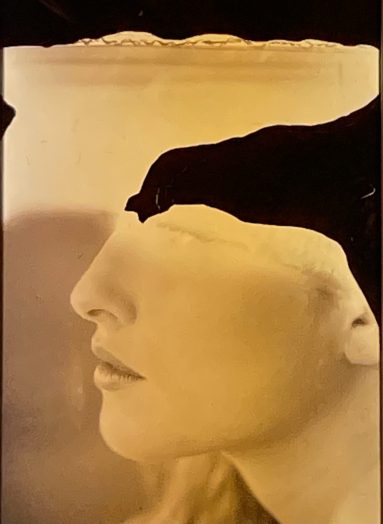

Film strip frame by Sante D’Orazio

D’Orazio’s world is populated by supermodels, actors, rock stars, and icons. His +30 year career has seen concurrent themes of eternal youth, stunning beauty, and rock and roll. D’Orazio’s portfolio is a mixture of informal and posed – an uncensored and provocative trademark. Since he first shot for Italian Vogue in 1981, D’Orazio’s work has been published in the likes of Andy Warhol’s Interview, Italian, French and British Vogue, Vanity Fair, and GQ among others.

In the final installment of their 3 part interview, Sante D’Orazio and Alexandra Kosloski discuss “nice accidents” and connecting with the unknown.

Continued from Part 2

AK: What was the most unexpected photograph you’ve ever made?

Sante D’Orazio: Well, in the editing process, a lot of times you’re shooting from one particular angle and you think it’s genius. And then for whatever reason, you try another angle, you do only two frames and think it’s not good, and go back to where it was before. And then you’ve got 500 frames of that angle you thought was so much better, and two frames of the one you tried, and those two are the best. Or something went wrong in the last frame and there’s a glitch, and that glitch makes it unique. That happened quite often when it was film, film offered more technical glitches that were wonderful.

That’s on film (right). It’s a Polaroid film, 35 millimeter film. That’s the last frame. So it’s a sticky film, where you peel off the emulsion. She’s like a Greek goddess.

AK: There’s such an intensity in her expression.

Photo of Tatjana Patitz by Sante D’Orazio

Sante D’Orazio: Here’s another picture (below). That’s from a glitch, too. So those are nice accidents. I was always doing experimental stuff that was more painterly.

Photo of Tatjana Patitz by Sante D’Orazio, 1989

I had all these pictures that I could never publish. A lot of naughty pictures, and they’re all famous people, and then one day I decided I would scratch everybody’s face out. And I did. And they were much better pictures. You didn’t need to know who they were. And then I bought a 70’s porn and I scratched out everybody’s face. Every frame. It took four months to scratch out 10 minutes. And so as the film moved and the scratches– 24 per second– all moved around, it became a moving abstraction. That was my first one. Then the second and third one, I used colored inks. And I not only had the film, but I would take individual frames and scan them and print them, so they were like little paintings.

AK: I like your series of priests, too. Could you talk about the little bit of the connection between art and religion?

Sante D’Orazio: The connection is not literal in terms of religion as we know it, especially not any kind of organized religion. Art to me is a means of connecting with the unknown, and that’s really what I think religion is; connecting with the source of being. Not all the time, and not all art, but certain art. That’s what it was for many of the abstract expressionists and the minimalists. It’s a means of connecting with the unknown. We all have different experiences, we have different beliefs, and it’s not literal, it’s the sensory perception.

Geometric paintings by Sante D’Orazio, installation in the artist’s studio

My geometric paintings are about how there’s a lot going on in what we can perceive and what we can’t sense. I was like, “How do I paint that?” Not the literal, but that sense. With those paintings, it was the geometric shape– the landscape creates a space between them that’s invisible. That’s what those paintings are about.

Everybody has a different approach to it, but I always tell people: learn how to stop thinking. Once you start thinking with the camera in your hand, you’ve lost the picture. If you had time to think, the picture’s gone. I’ve told that to some very famous painters, and they went from taking shit pictures to taking some really good ones, because they got it. They were already doing that in their paintings, they realized that they could do that in their photographs. I think it applies to every art form; dance and music. Stop thinking. You do all the thinking in between, all the thinking you want. But once you get to it, stop thinking. Feel. It’s all feel. All sense perception. That’s the language of that connection that you have with the unknown. It’s all a sensory thing. That’s the only connection you have.

AK: Lastly, could we talk a little bit more about your current projects?

Sante D’Orazio: Presently, I finished the memoir and I’m looking for a publisher. Then I want to finish editing the archive, discovering new pictures. I can make a new book from those pictures, and maybe I can throw in some of the writings from the memoir into that book that pertained to photography. I’m revisiting an old script that I didn’t get to develop. I’m more ready now than ever before, so I’m back to that. I would like to direct a film. I wouldn’t mind getting back to my painting work. And you know what I would love more than anything? I would love to do some great photo projects. I just went to London three weeks ago and shot Guns N Roses in Hyde Park. That was my first photo assignment in seven years. I got some great pictures, and that was exciting. Otherwise, I shoot on my own. I still love shooting nudes because I started by drawing nudes. I was never really a fashion photographer. I learned how to do it, but I was always a beauty photographer.

An Interview with Sante D’Orazio (Part 3) Read More »

Interview