Memento Mori

Antonio de Pereda, El Sueño Del Caballero (The Gentleman’s Dream), c. 1650

On the banner: Aeterne pungit, cito volat et occidit “Eternally it stings, swiftly it flies and it kills”

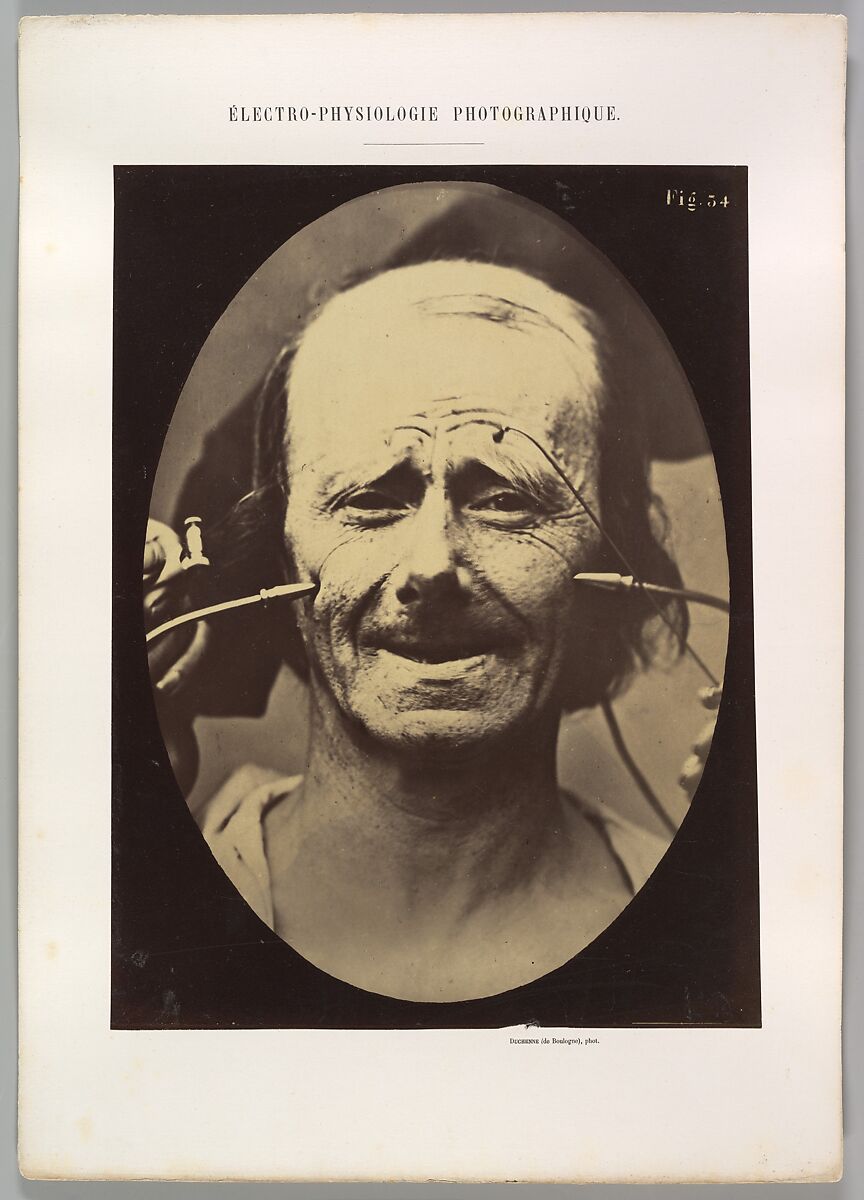

Memento Mori, the latin phrase meaning “reminder of death”, began to occur in medieval art as a visual manifestation of the ephemeral nature of life. While the concept can be traced back to the ancient, it became popular in art with the rise of christianity and its philosophy that life is fleeting, earthly desires are distraction and the salvation of the afterlife is eternal. Past the renaissance and as time went on, memento mori became more secular, and refers generally to the brevity of life and the importance of the present moment.

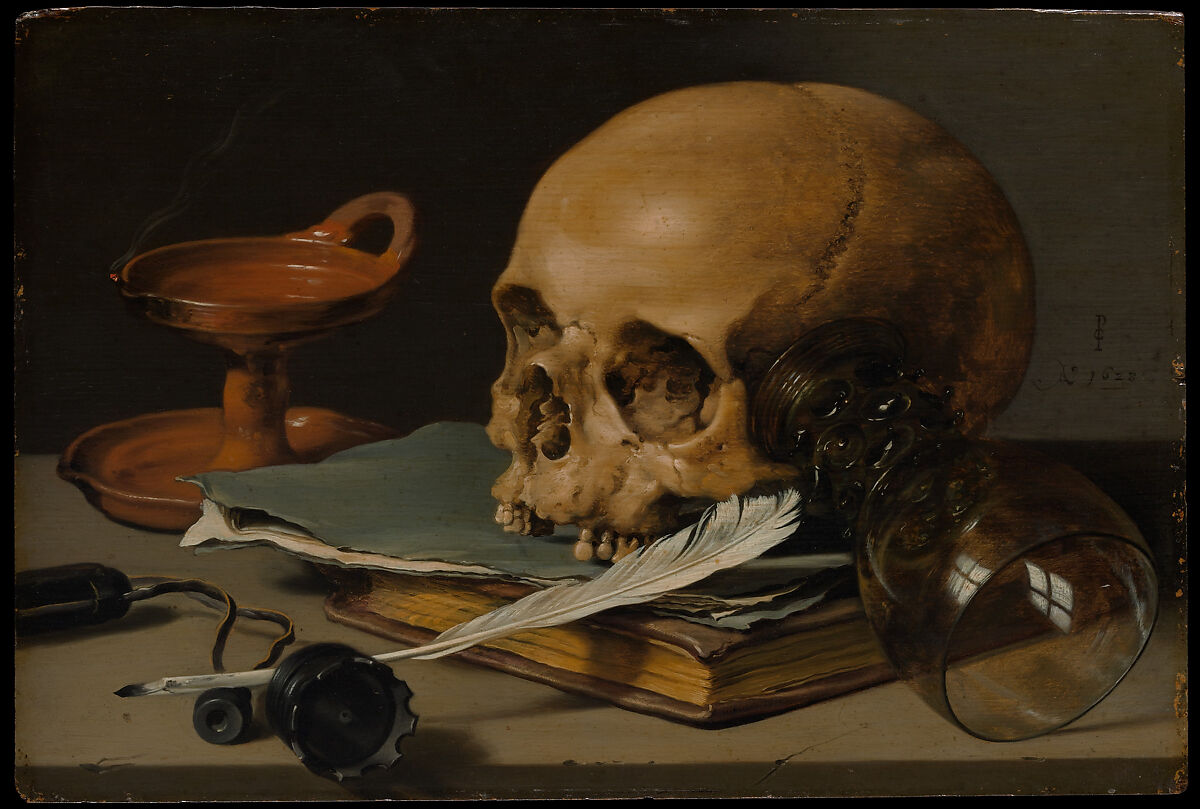

Typically symbolized by skeletons, candles, hourglasses, decaying objects like wilting flowers or rotting fruit, this imagery represents the passage of time and the certainty of death. These motifs can be noticed in anything across contemporary visual media, such as film or fashion, but were originally embodied in small objects like prayer beads or jewelry, as well as sculpture or painting. In the 16th century, Dutch painters began the production of Vanitas paintings; allegorical still lifes of a collection of symbolic objects indicating morality, often relating to piety and memento mori.

The memento mori challenges the viewer to look closely, to hold the image in their mind without immediately reacting to what may be an unsettling visual. To reflect on the art, the viewer’s own life and ultimate death.

Pieter Claesz, Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill, 1628, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art