Terracotta rim fragment of a kylix, 460-450 BCECourtesy of the Met Museum

“I seek not good fortune. I myself am good fortune.”

-Walt Whitman

This may be the smartest advice on art investment you will ever read, and yet there will be no proofs, charts or diagrams. It is extracted from a full life’s experience, itself built on my father’s life’s experience, the wisdom of which he shared readily with anyone who would listen, but especially with me. It’s about collecting art from a love of art and not in order to make money. And while I can’t promise you will make money this way, as that is not the stated intention, I also can’t see how you would fail. Yet in the end, perhaps the greatest rewards are entirely impractical, utterly ineffable, and most enriching. If energy of work and bright ideas are represented by money, the energy of inspired genius and all the best of the human spirit is represented by art, so to trade the former for the latter, we are always getting the best deal.

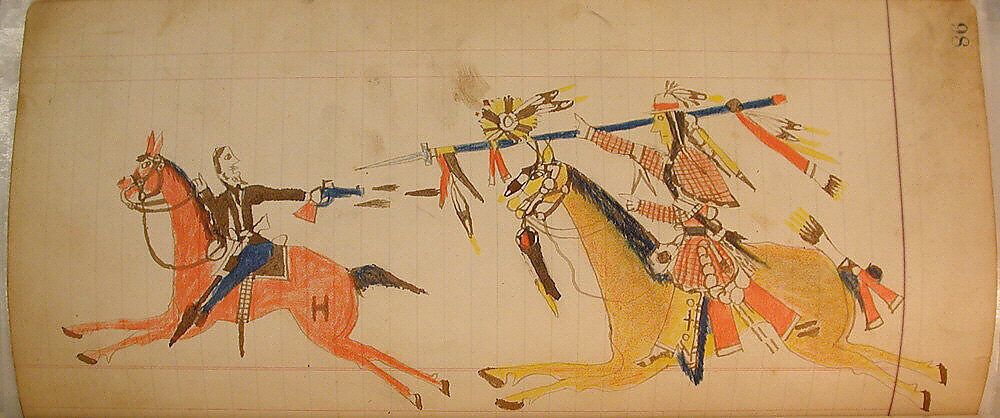

Maffet Ledger, 1874-81, Courtesy of the Met Museum

I hate to sound like a paradoxical fortune cookie so it’s best to draw from life experience examples. When I was a teenager I thought I was smart. So smart that I knew Picasso sucked, and that anybody who liked Picasso was stupid or brainwashed. Then my father was the middle man on a big Picasso deal and an important Picasso hung in our living room, replacing a particularly joyous Miro I loved seeing daily in passing. Now, this Picasso was so expensive that it was a special kind of ugly. That stripped down Madrid palette: black, white, gray and shitty ochre. Plus all the bells and whistles of distorted facial features. A travesty. I complained when it went up, passed it with a shudder and couldn’t wait for it to be sold, so we could reinstate the Miro, and probably fly to Europe for a celebration of the big sale as was our wont.

After a night of drinking I reclined on the sofa still swaddled in my blanket, eating a bowl of cereal and watching rap videos on MTV. I looked over at the horrible Picasso, back at Public Enemy... and then back at the Picasso. Something happened. A light went on. I can’t explain what occurred psychologically but probably something like a million brain synapses firing at once, and from that point on I could stand toe to toe with John Richardson and debate Picasso. And he was every bit as topical to date as my favorite rappers. I saw.

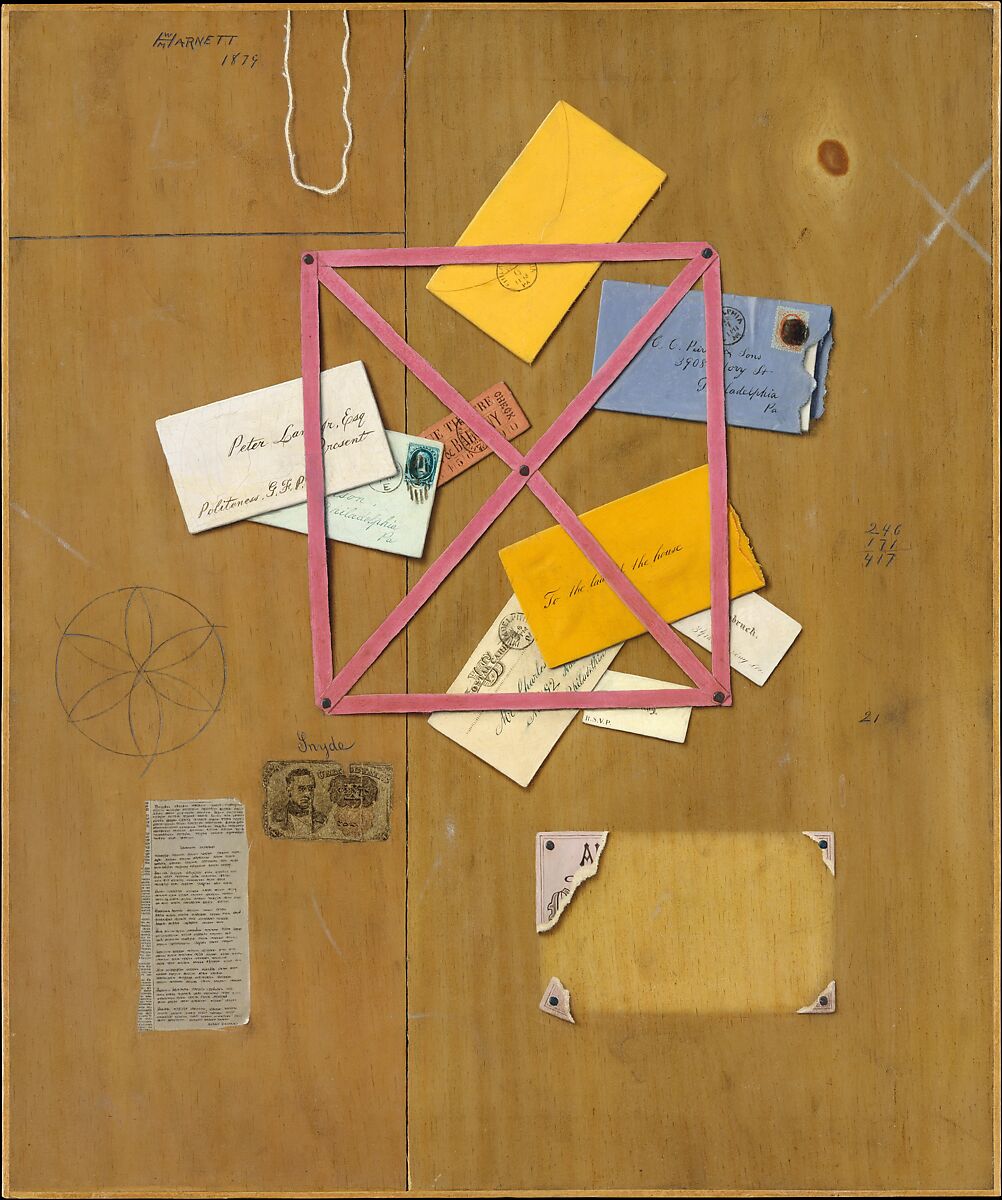

William Michael Harnett, The Artist's Letter Rack , 1879, Courtesy of the Met Museum

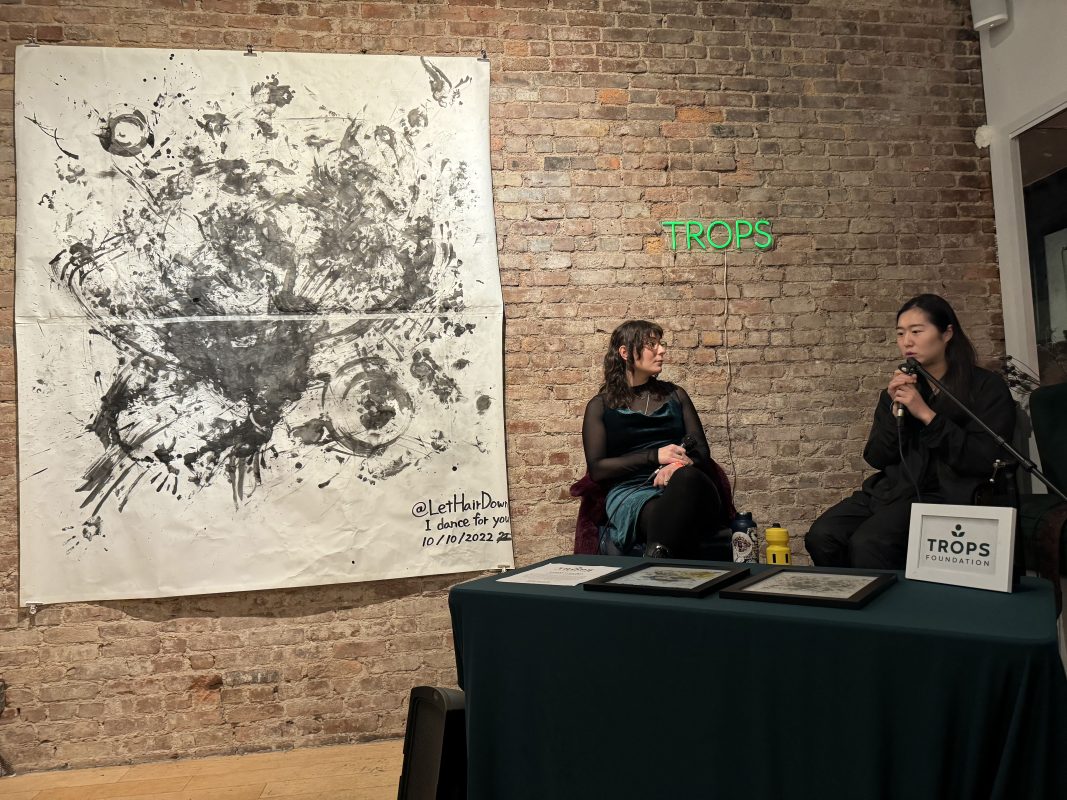

I was a graffiti artist on the subway scene. Whenever the big guys in this underground movement had an exhibit above ground, Futura, Dondi, Rammellzee or Lee Quinones, everybody in the civilized world showed up. So as a card carrying member of this closed society, I thought of all the zillionaires and movie stars as mere hangers on. But then there came a wave of artists in their own right, very interesting ones, who brought a new kind of synergy to this popular avant garde. Luminaries like Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Richard Hambleton, Martin Wong, and David Wojnarowicz. This new wave of innovation was not driven by marketing or PR but– to use Robert Faris Thompson’s specialty term– because it was “cool”.

When Fun Gallery showed Basquiat we all went to the opening. Hands down one of the coolest guys downtown. Neck and neck with Rammellzee. The paintings that still smelled of fresh oil stick were $1,200 or maybe just an even grand. And Dad and I were in that group of New Yorker insiders, with money to spend, yet none of us, nobody... bought one.

Strangely, nowadays collectors only want to buy a Basquiat. It’s seen as safe, as blue chip. A (cringe) status symbol. I even meet people who want to make a million dollars SO they can buy a Basquiat. To buy and live with a Basquiat absolutely has value today, such as if one bought a Picasso or DeKooning, the investment should appreciate, and the art will radiate its riches. But clearly the best time to buy was at that Fun Gallery show. When the work was new, the ideas were raw, the artist was alive, young and hungry, living dangerously and needed the sale. Again, nobody bought one.Basquiat, in the arc of his mayfly short life, enjoyed success. However, we continually fail to recognize and support young artists, specifically, and art as a whole when we are not there to applaud a genius on their debut on the world stage.

Excluding most of the artists present at the Fun Gallery opening, everyone in that room could have afforded a Basquiat or ten, would have helped the world to be a more beautiful place, and oh my– was there a dollar to be made. But even the rich never seem to be rich enough to invest in art where it counts, in that unpredictable liminal phase, where the work is exciting and not yet market proven.

Pere Oller, Mourner, ca. 1417 , Courtesy of the Met Museum

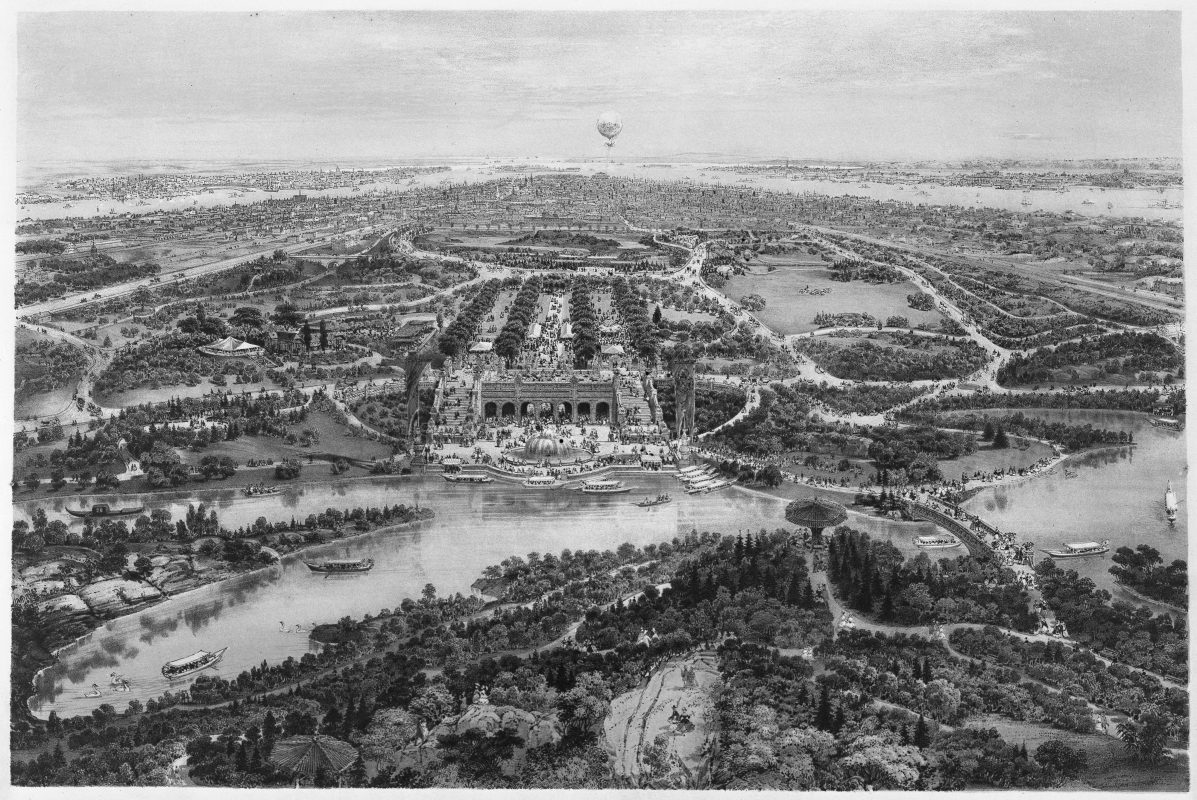

It takes a hero, like that great collector couple. I forget their names, but I watched the documentary- the husband drove a taxi for a living. They loved art and went to all the openings together. They would fall in love with a picture, say a Rauschenberg, and tell the gallery they would pay it off little by little, from paltry wages. In this humble way this enchanted couple cobbled together a world class collection and became fabulously wealthy, but most importantly, lived surrounded by the powerful magnetic field of their passions.

My father left a stint in the military to hang around the Abstract Expressionists, Beat Poets and Be-Bop musicians, and caught the tail end of all that. He was a teenager working in an art supply store when he met Warhol, who was then still in advertising. Andy asked Pops to take a freshly minted soup can for a walk up Madison Avenue to see what he could get for them. It’s mentioned in the diaries later that “Rick Librizzi [dad] sells my prints too cheap”. And dad was never all about the money, but later I think it did affect him when we sat at Christie’s watching works he sold at 30 or 50K skyrocket to Lotto jackpot figures. Either that or his seat was very uncomfortable.

Nevertheless, he rationalized it, recalling that was the year we rented the suite at the Negresco with the sea view like Matisse. After all, Pops was born dirt poor and believed you could never make every dollar, but had to get some life lived while you had the chance. Maybe I’m wandering off topic a bit, but staying rooted in experience is the best way to show, not tell, the many ways collecting art enhances our human experience. And to invest means not just our money, but our energy, power to believe, and generosity in humble open mindedness, so that even dressed in rags we know an angel when we see one.

When I lived with my dad it was only a matter of time before calls came in from museums requesting the loan of some painting he had paid, literally, fifty dollars for, so when I came of age, I made it a point to collect every notable talent at the moment they emerged from the woodshed. True, some artists materialize on the scene, to be lauded as the toast of the town for a season, only to be damned to obscurity afresh by autumn. And if intrinsic value is anything, qualitatively some of my favorite works come from fringe names that may be lost forever to time, like some anonymous Egyptian or Greek hand. But with every crop of promising talents there is generally one, sometimes two, or in a blessed vintage three who keep at it, and keep striking that sweet spot of relevance until they become household names. This is when your head and heart can agree that your time and energy was well spent. The rise of the one artist who establishes a market pays for the lot of investments, and perhaps your own celebratory tour of European capitals on payday.

Nesting Bowl, 460-450 BCE, Courtesy of the Met Museum

Along with the dilettante who brags about a sound investment in secondary market stock, is the novice Art Historian who can downplay Picasso’s importance, perhaps citing some of his horrible personality traits, chats to be enjoyed while waiting in line for a table at the latest celebrity chef eatery, drawn in by glowing reviews heard on a television program. An entire art-world whose stance is anti-innovation, or even anti-Art. Art as a luxury item. But to venture out as a pioneer on the still-cooling volcanic horizons of a new landscape forged by a visionary avant-garde, that is where real thrills are to be had, together with risks.

When Dad was collecting East Village artists and supporting the graffiti movement, Richard Hambleton rose from anonymity, painting his menacing shadow man figures on the abandoned streets to an “overnight” art stardom bypassing the entry level investment phase favored by my father. Dad would buy cheap and sell dear as a rule, but from a distance treasured what Hambleton had contributed to the tradition. Pollock had abandoned representation for the sake of the vital gesture, and then turned around abruptly to shock and offend the art public by returning to the figure. Critic and collector felt betrayed by the ex-abstractionist, and he by them. Hambleton, according to my father, came along to push this lost cause to a solution, applying the Ab-Ex dynamic to all-American classic subject matter.

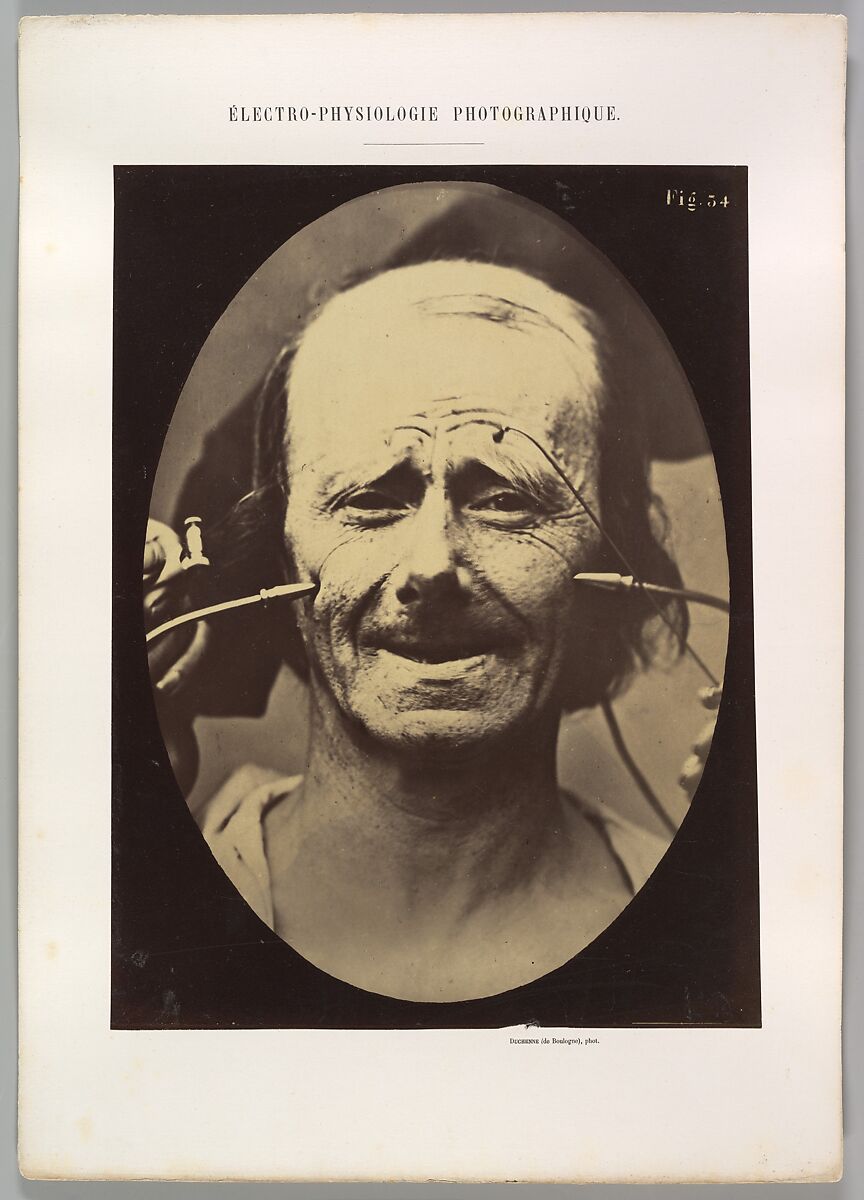

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne, Grimace, 1854, Courtesy of the Met Museum

Yet a decade later, Richard would approach my father in the park, humbly asking if he might be interested in buying an ass-kicking rodeo painting tied to the back of his old bicycle. By then Hambleton had tumbled from the ivory tower of bohemian royalty, and thus began a friendship that doubled as a symbiotic business partnership. Dad bought as many paintings as he had room for, and sold off the others to friends and collectors. And at some point my own friendship with Richard blossomed into a business alliance. I bought as many as I could hang on my walls, and visited his studio with fashion models, and pot dealers, and anyone I might encounter with means to acquire something beautiful, and with inherent value well beyond the asking price. Everyone who bought at this stage, and supported a distressed genius, was thrilled by this meaningful exchange, only some were later disgruntled when powerful agencies aligned with our family efforts restoring his market where it belonged– disgruntled that we had not effectively convinced them to invest in time.

Although I am no psychic, it did not surprise me to see Hambleton’s prices spike at the end of his life. And it was not a mere question of engineering, either. But when an artist is that authentic, that tied in with history, that unique and innovative, generally it's merely a question of time before the trade catches up. In the annals there are of course cases like Picasso’s: a staunch purist who never resorted to charlatanism, who seized the reigns of a thriving career at a young age persevering for the next sixty years with nary a hiccup, persisting to this day as gold standard. Or Van Gogh’s, who suffered the torments of the damned in his lifetime without any respite in worldly success, who nevertheless has in time reached the hearts of zillions. And yes, the works have grown to be treasured as priceless. That a Van Gogh painting never was worthless, however unsaleable they may have been during his lifetime, therein lies the question and answer to absolute value in Art. First and foremost we must appraise an artwork for its potency in conveying human feeling. And when it succeeds at that, Art always generates a profit well beyond any financial return, even when it's not resold.

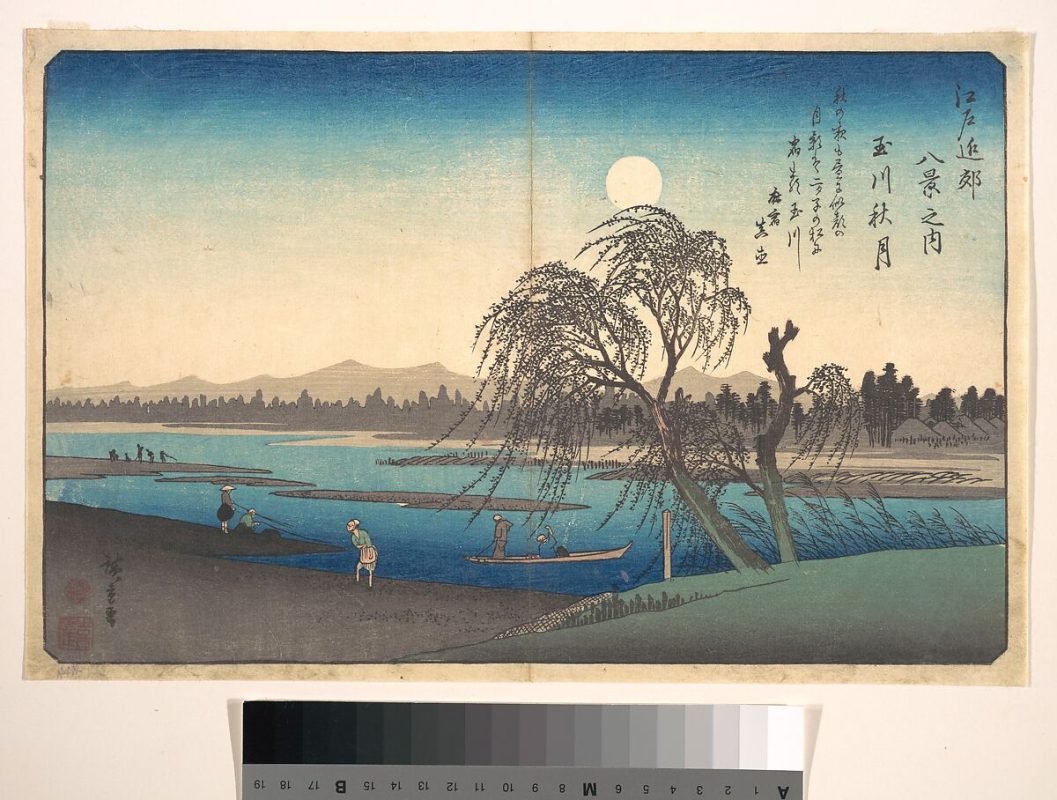

Keisai Eisen,Winter Landscape, 460-450 BCE, Courtesy of the Met Museum

When I was a teenager Jean Michel Basquiat made me a great drawing, employing his key iconography, and I had it framed and lived with it for many years. When I became a father, I never saw bills come crashing in so quickly, so with regret I brought this sacred relic to an auction house. Whereupon they asked me for the paperwork. It had never occurred to me to have the damn thing pedigreed, and now was made to understand that the board was no longer considering certifications. I was met with disappointment, to find this precious item ripped of its price, but met my fiscal challenge in some other manner. And I continue to live with this spark of genius, that might have easily been traded in for a sack of rice, but continues to inspire and bring joy to my household instead… in that intangible way that poetry can always nourish us where bread fails.