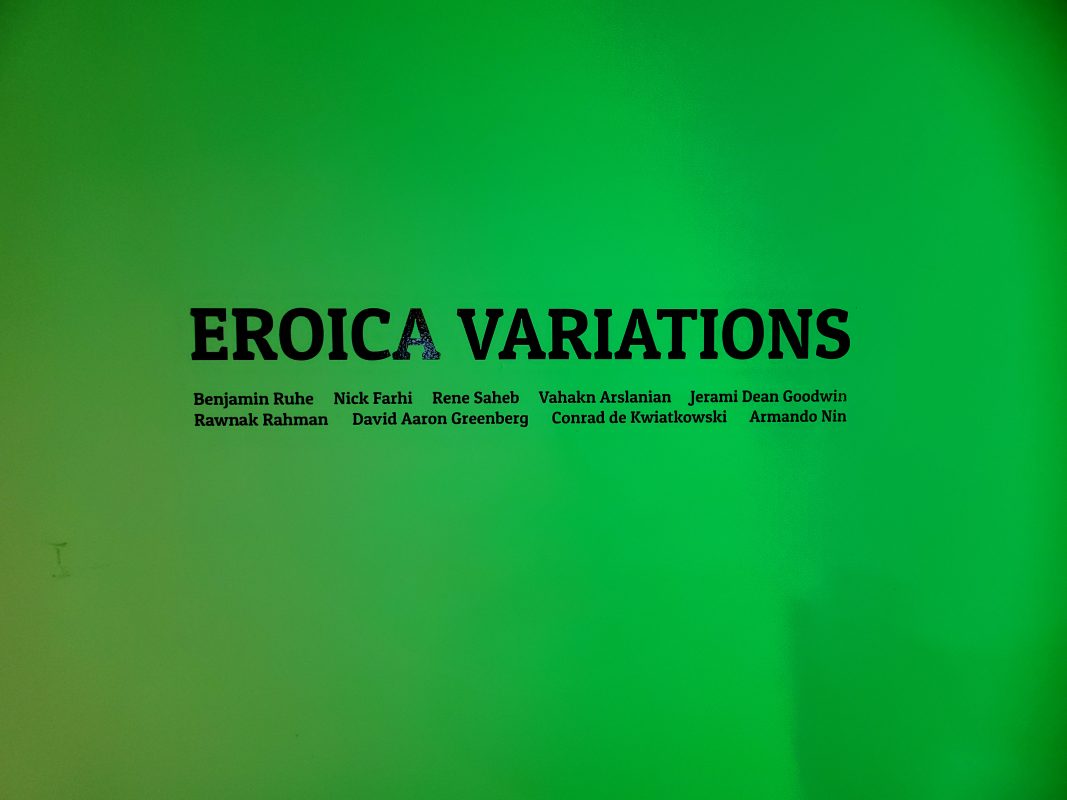

Poetry and music by Haleh Liza Gafori & Shahzad Ismalily

Haleh Liza Gafori is a translator, vocalist, poet, and educator born in New York City of Iranian/Persian descent. Gafori aims to transmit the whirling movement and leaping progression of thought and imagery in Rumi’s poems into the music of contemporary American poetry. Gafori believes his words offer liberating and nourishing perspectives vital to our times, inviting us into deeper levels of compassion and generosity.

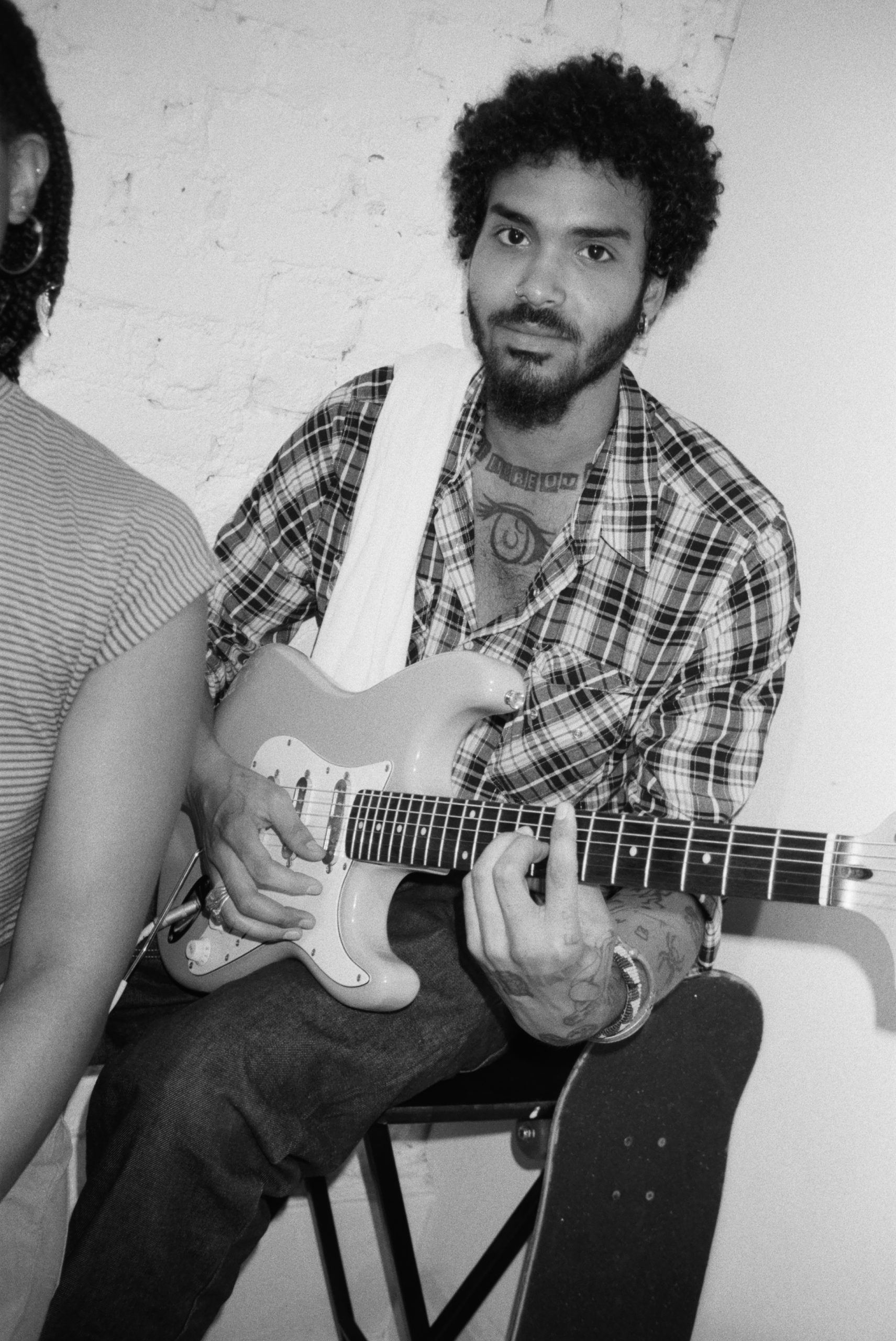

Shahzad Ismaily was born in the States to Pakistani parents who emigrated here just before his birth. He grew in a bicultural household, always following a multitude of paths and perusals. He is mostly self-taught as a musician, composer, recording engineer, and producer.

Poetry by Judith Fleishman

Judith Dimitria Fleshman (b. 1958) is a visual artist, performer and writer who lives and works in New York City. In 2003, Abaton Book Company published her text/visual collaboration Looking for Maya and her prose has been published by Tema Celeste, Rogue Magazine and the artist zine The Orifice. Fleishman’s work can be found in many private and public collections, such as The Museum of Modern Art, The NYC Public Library, the Gemente Museum Arnhem, Netherlands, and The Ludwig Museum in Cologne, Germany.

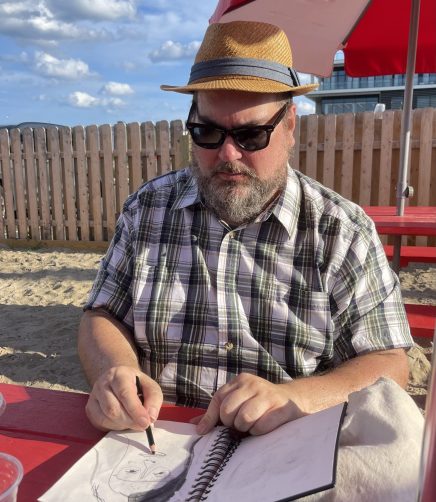

Poetry by Anthony Haden Guest

Anthony Haden-Guest is a British-American writer, reporter, cartoonist, art critic, poet, and socialite who lives in New York City and London. He is a frequent contributor to major magazines and has had several books published.

Music by Mehrnam Rastegari, Martin Shamoonpour, John Murchison

Mehrnam Rastegari is a well-established Iranian musician and film score composer, singer, violinist, and master Kamancheh player. She has been featured in concerts and music festivals worldwide. Her art reflects her interest in the juxtaposition of cultures. She believes that in current times the most valuable arts are those which most people with different languages can feel connected.

Martin Shamoonpour is an autodidactic multi-instrumentalist, composer, actor, and visual artist from Tehran. He was born in 1984 in an Assyrian family. One of the most important works of Martin Shamoonpour in the field of music is the publication of sermon on the mount, Tehransaranieh, 8 Bit and Ear Magazines.

John Murchison is a Brooklyn-based bassist and multi-instrumentalist. He is known for his active role in several musical circles, performing primarily in pop and musical theater, jazz and avant-garde, and traditional musics from the Middle East and Africa.

Poetry by Leah Elimeliah

Leah Kogen-Elimeliah is a poet, essayist, short story and nonfiction writer from Moscow, currently living in New York City. She is an MFA candidate at City College of New York, the Founder of the WordShedNYC Reading Series and an Editorial Associate for Fiction literary magazine. Her writing focuses on identity, language, sexuality and culture. Leah lives in Manhattan with her husband and their children.

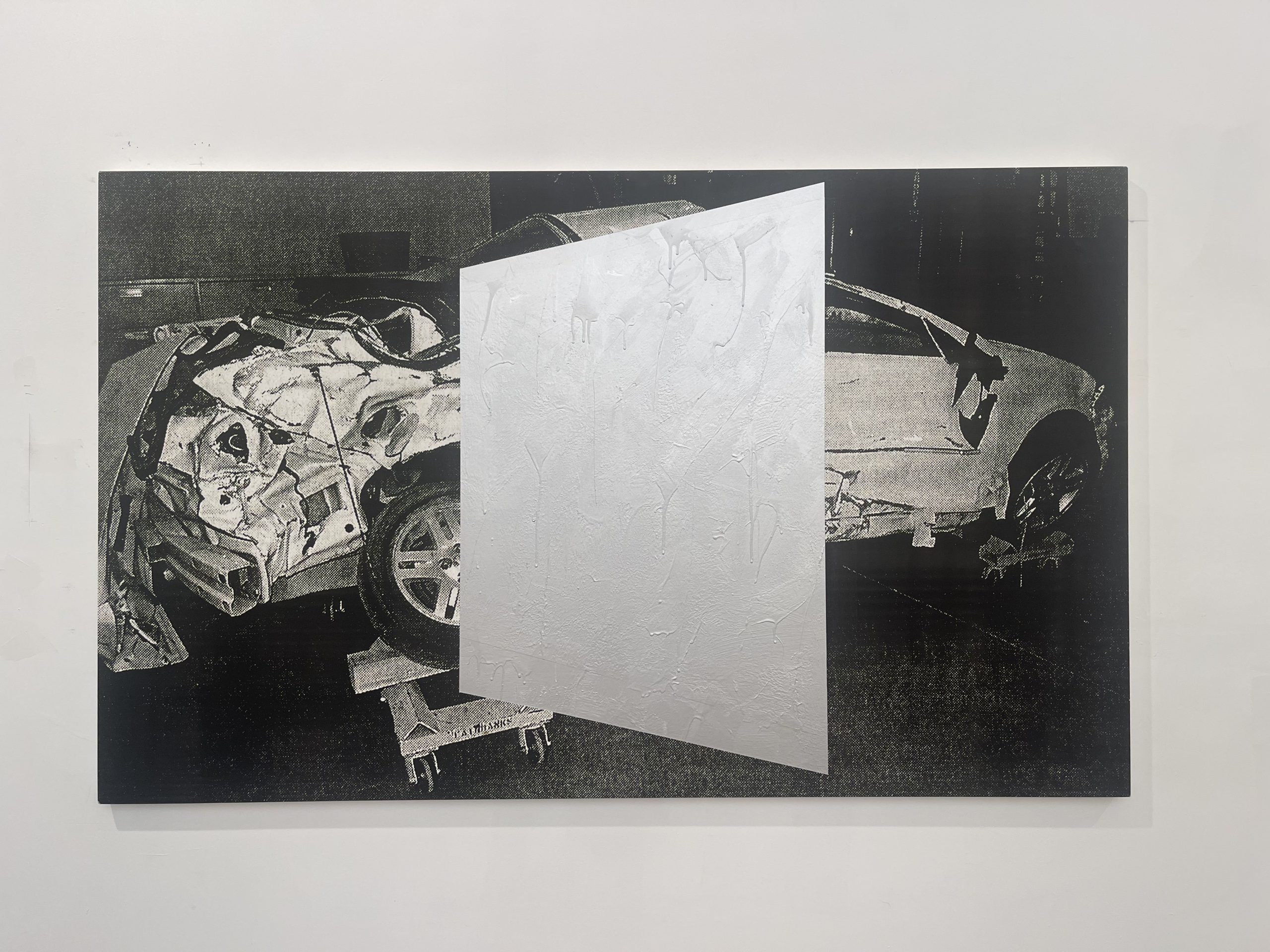

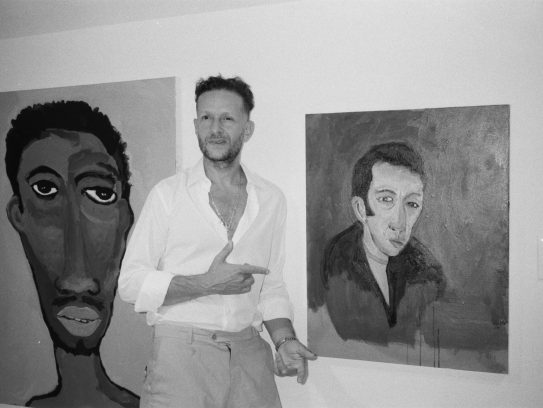

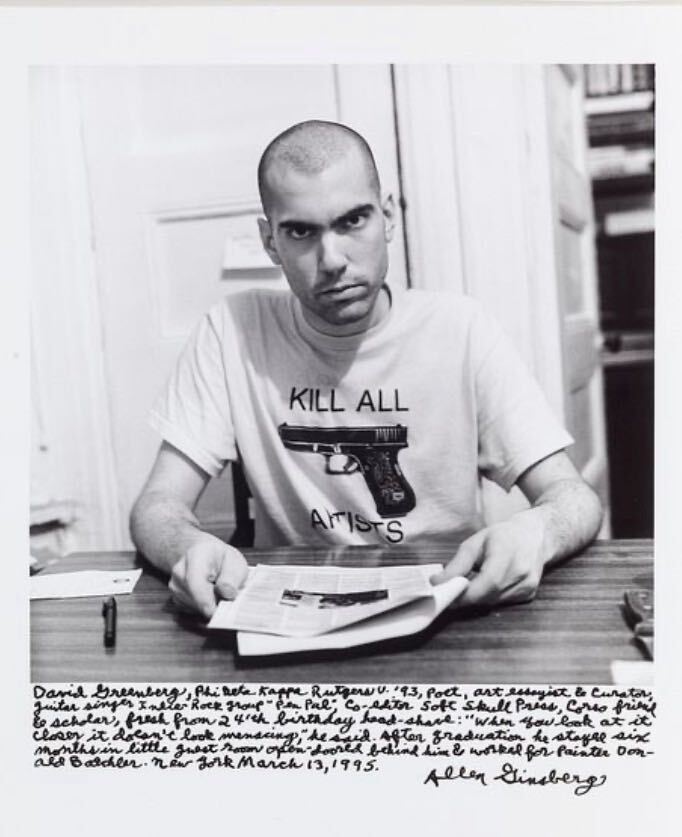

Poetry by David Aaron Greenberg

David Aaron Greenberg is an artist who uses multiple modes of expression.His work has been exhibited in various New York City galleries and is in the permanent collection at Stanford University. His critical writing has appeared in Parkett, The Fader, Art in America and Whitehot Magazine. Along with producer David Sisko, he co-founded Disco Pusher, a New York City songwriting and recording duo. Greenberg graduated from Rutgers University, Phi Beta Kappa. He lives in New Jersey and sometimes New York City.

Music by Sandflower

Brooklyn-based Sandflower is an artist with interests as varied as her sound. Drawing on the contrast of the buttoned-up academia of her private school upbringing against New York’s vibrant music scene, the artist cites everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Cindy Sherman, Salvador Dalí to Allen Ginsberg as inspirations for her own blend of rap-infused pop.

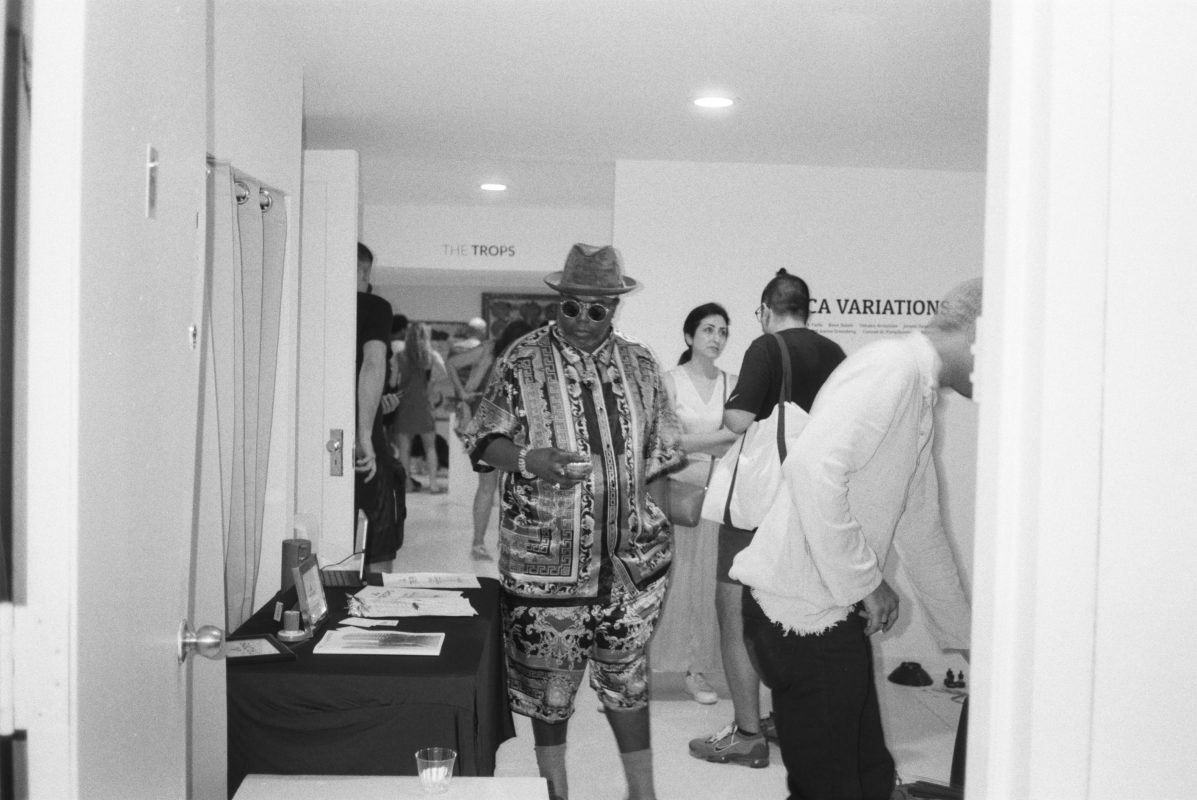

DJ Milo

Milo Carney was born and raised in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn. He graduated from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in May 2010, with a focus on printmaking and sculpture. Milo is currently working as a preschool teacher at The Saint Ann’s School where he attended elementary and high school. He enjoys cooking, modifying clothing and deejaying during ‘free-choice.’ His art questions the effort of one’s own involvement in a cause and examines the futility of caring as well the difficulty of discernment.