An Interview with JonOne (Part 2)

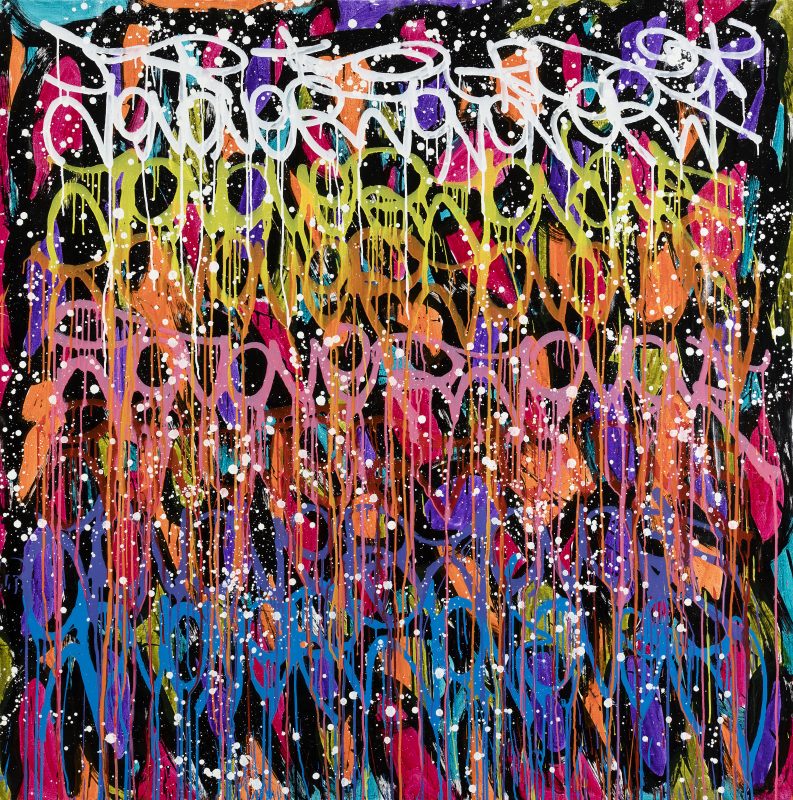

JonOne

Push the Buttons

Photo by Bruno Brounch

John Perello, AKA JonOne or Jon156, is an American graffiti artist living and working in Paris. In 1984, he founded the graffiti group 156 All Starz, before relocating to Paris in 1987, where he quickly made a name for himself. Working on a wealth of projects during his long career, and exhibiting on a global scale, his style is colorful and expressive.

In part 2 of their 3 part interview, JonOne tells Alexandra Kosloski about the state of his practice and his unique approach in life and art.

Continued from Part 1

AK: Do you ever feel like your experience with graffiti gave you a particular advantage– or maybe a disadvantage– in the institutional art world?

JonOne: Well, I’ve always been an outsider. It would be nice, of course, to be challenged in a lot of different types of areas, but you cannot be everywhere or satisfy everyone. So, what I try to do is create an exciting life for myself above everything. I try to– no matter what opportunities are given to me– I try to live my life. As I should be living my life, you know, and not depend on people, that they’re gonna come and save my day. I really don’t believe in that. Sometimes it happens, it’s always a payoff to do anyway. But I tried to live in a free way, no matter what.

Because it was just so hard to access the art world. It’s just so complicated. And what’s difficult is to be able to continue throughout all the years, and I’m very grateful. Forty years, I’m still painting, and I have a studio and I have assistants– which is tiring. And I was able to raise a family through art, so I’m grateful for the things I have and the things that I don’t have. Well, whatever. Maybe it’ll come around later on– yeah, I wouldn’t mind doing a museum show. You know, why not?

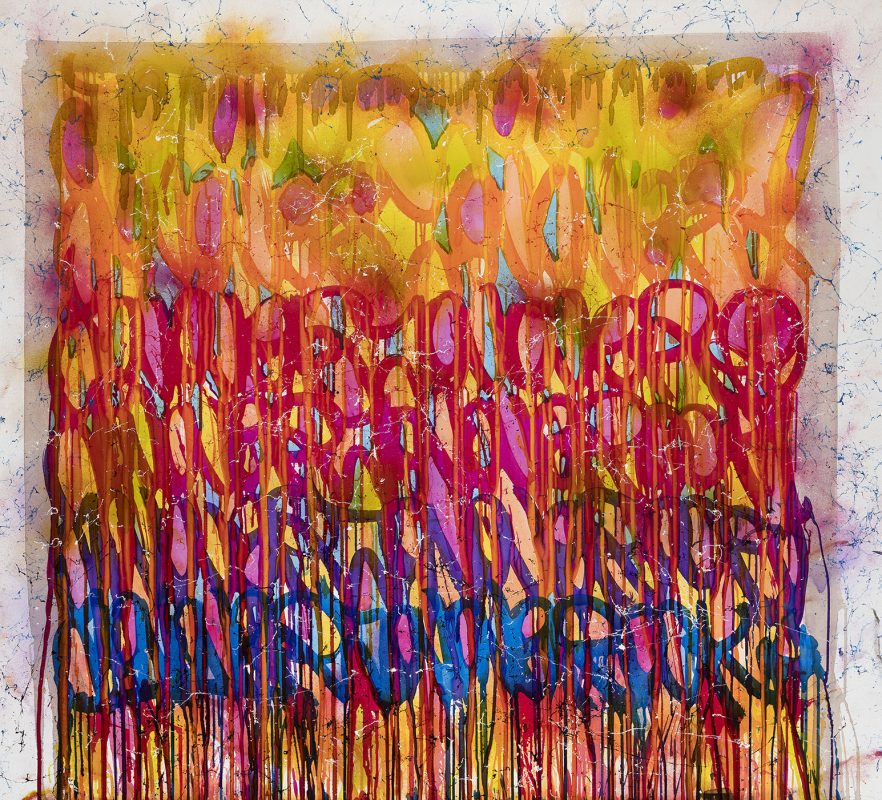

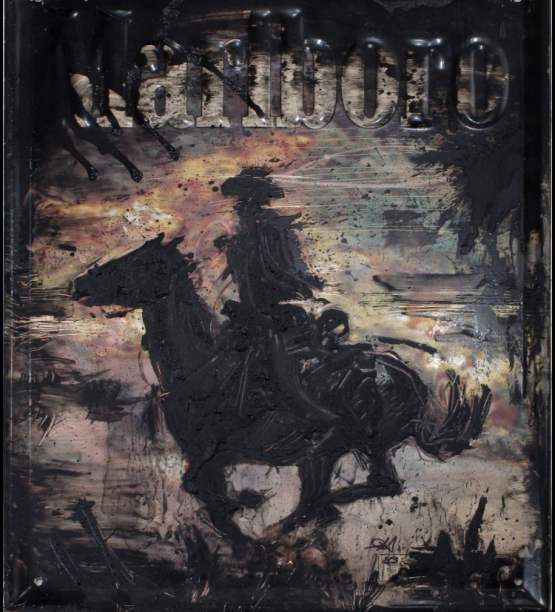

JonOne

Civil Rights

Photo by Bruno Brounch

AK: So why did you move in that direction? Because going from what you’re describing at the start to mentioning a museum show– it feels like there’s some steps to take in between that. What was the catalyst for that?

JonOne: Like to go from, let’s say, vandalism or graffiti– which is beautiful also– to working inside doing canvases and things like that.

AK: Right. And I’ll pinpoint your move from New York to Paris, did that move play a role?

JonOne: Oh, yeah, it was one of the best moves ever made in my life, to have moved. It was like I was blessed.

But you know, it wasn’t like I was blessed. I always had a vision of being different. So when I say, hip hop, and all that stuff… I was always listening to a lot of different types of music. I was hanging out with a lot of different types of people. I wasn’t just limiting myself to hang out with Blacks, or Hispanics, I hung out with a lot of different people from all over the world. I already spoke two languages, which were Spanish and English. And I was very open to things. I wasn’t just uptown, I was hanging out a lot downtown. So for me to find myself in Paris, there’s no coincidences, right. Even today, I listen to a lot of different types of music, a lot of different types of dads. It’s a way of cultivating myself. So to have moved to France, it was just a transition for me that was like, okay, I really experienced New York, let me see what I can do here. And that’s the way it just became a way of moving on and spreading my art to other people.

AK: It just felt like a logical next step.

JonOne: Yeah. Because at the time when I left New York, the trains were being painted over. And they were really hard on graffiti writers, on vandals, really, really hard. Which they shouldn’t have been because in Europe, everybody was more cool about it there. And New York was supposed to be the land of free and the brave and all that stuff, but they were too much– just too… you know.

So here, I was able to continue to paint freely and not feel like I was being persecuted. A little bit like the jazz musicians were; that moved from New York or from the US and moved over to Europe, that felt more free expressing themselves in Europe than in the States. That’s the way I felt.

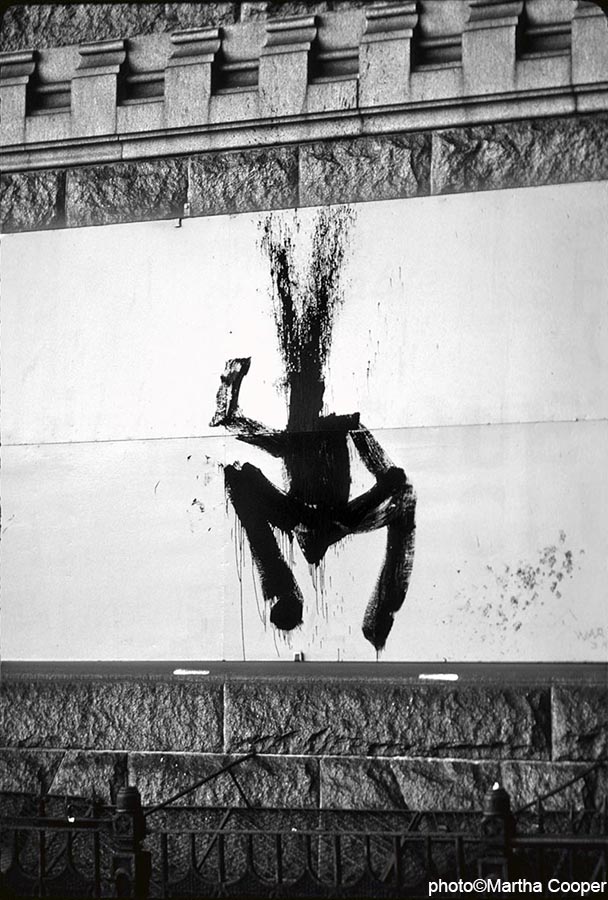

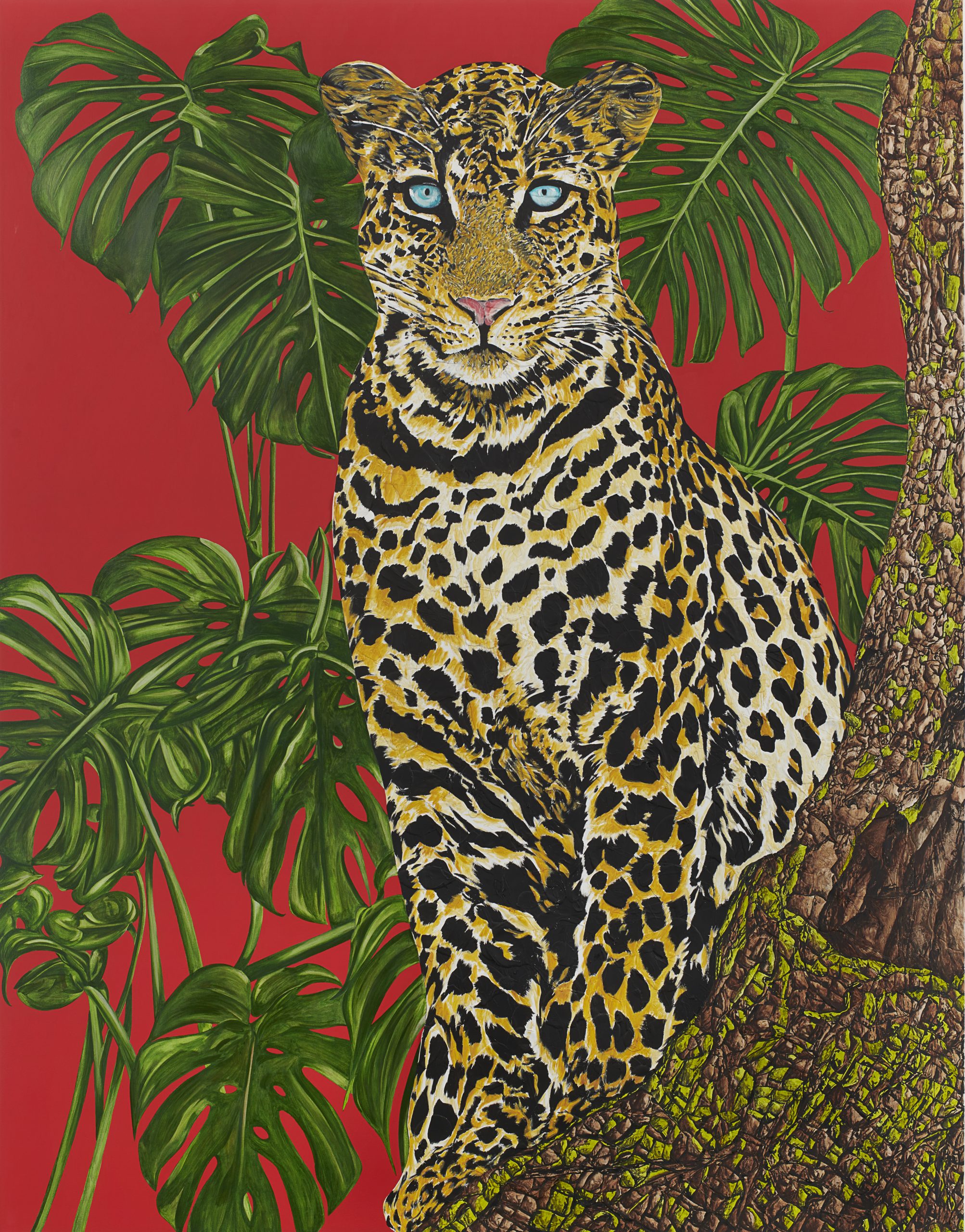

JonOne

Cool It Down

Photo by Bruno Brounch

AK: I do want to talk more about painting. What does a typical day in a studio look like for you?

JonOne: Well, it’s very complicated working in a studio for me. I was thinking about that today because some people from the outside world– they don’t really understand. It’s not like when you start, like when you’re a young artist, you got less baggage. But as you get older, you get more baggage to carry. It’s like the difference between dating a young guy and dating an older guy. The older guy looks good and everything, but he has all this baggage and you’re not really sure if you want to deal with this. Because you might want to just spend time with the guy, but the guy may be so complicated, you know.

Like when you paint for a while, things become more complicated. I mean, creativity wise, I’ve gained a lot of experiences throughout all the years, and that’s something that you can’t take away from me, because I’ve done a lot of different types of projects, and I know my craft pretty well, I know how to express myself, so that’s all good.

But at the same time, you create expenses around you. So when you create expenses, then you got to deal with a lot of different types of people that are gonna free you up in a way so that you’re not stressed out in your studio that much.

So that’s the baseline. Now, a typical day in my studio, I try to start by taking care of myself, first of all, because you need a good body to paint. So I go to the gym and I come here around 11 o’clock. And then I got to deal with assistants that are waiting for me to tell them what I want to do. I got people here that are going to ask me questions, you know, I’m not like, alone in my studio and just creating, listening to music. So I’ve got to deal with them first, right. And once I get them out the way and they beat, then I can paint. But then I got my girl calling me up, and I got the kids– you know, it’s complicated to create. But I’m here right now and I’m painting.

So there’s challenges at every level, at every level when you paint. So like I was saying, I went to a lot of different types of places recently– I was in South Africa and Bangkok, Alabama, I was in London. I absorbed a lot of different inspirations and I met a lot of different types of incredible people, so now when I find myself alone in the studio, I try to express that energy into my paintings. That’s what makes it so unique, my paintings. And so exciting. So right now I’m working on five, six… like 10 paintings at the same time. You know?

AK: That’s a lot.

JonOne: Yeah.

AK: You work on them all simultaneously?

JonOne: Well, some are drawings, right now as we talk. And some of them are going to leave the studio tomorrow. And some of them I’m working on right now. It turns around a lot. I have a really small studio. It’s tiny, tiny, tiny. So I’m bouncing around the place a bit.

AK: That’s interesting. So it sounds like you have to try to have a clear mind, minimize distraction, and that’s when you get the work done.

JonOne: Exactly. You said it pretty good. I have constantly tried to prioritize things and say “that’s not really what’s important”.

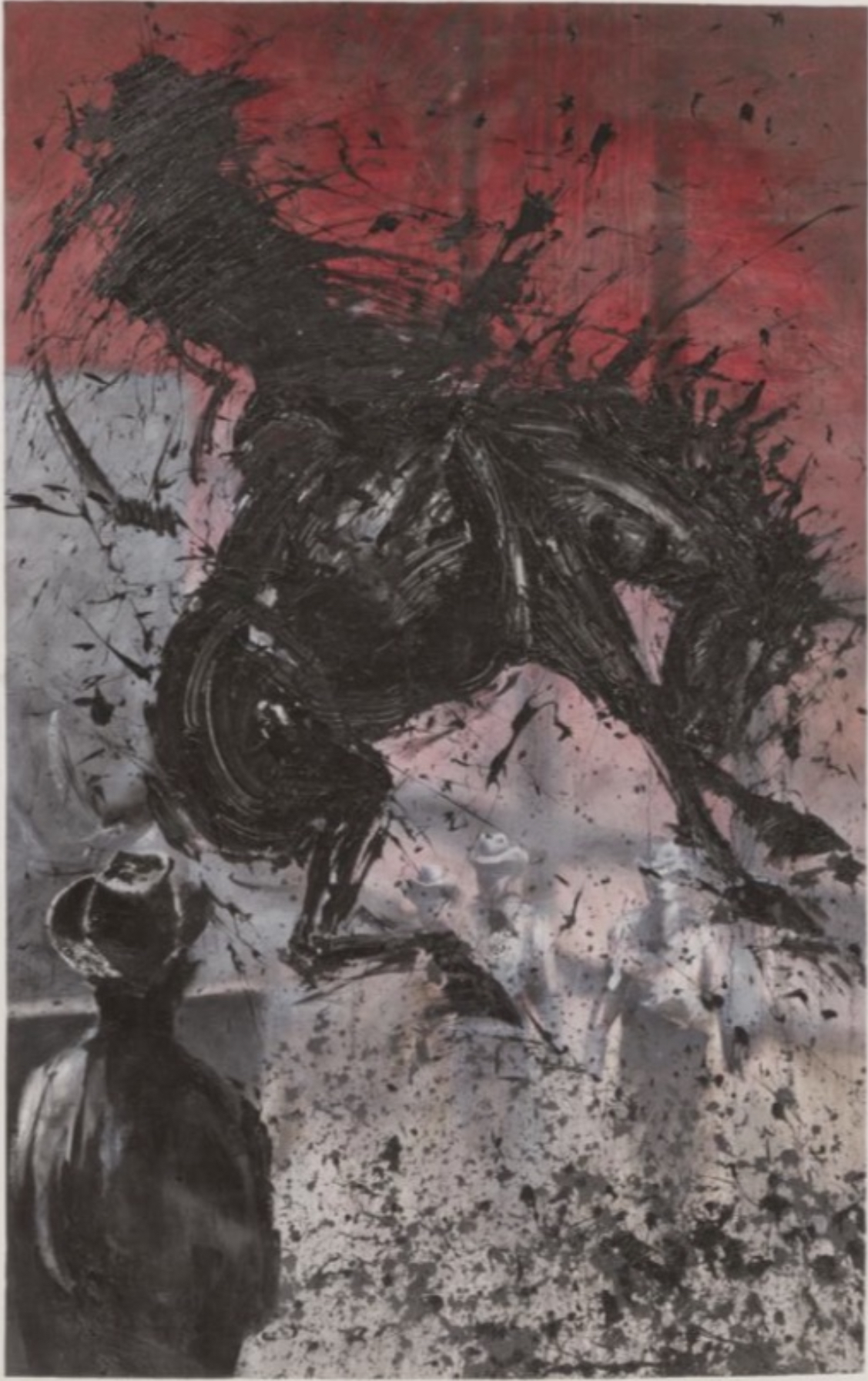

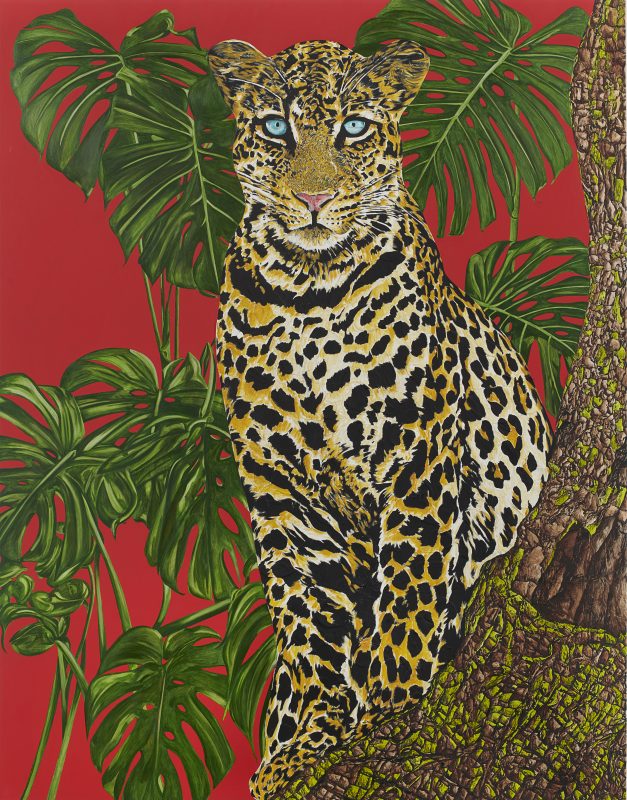

JonOne

My Heart Is Fragile

Photo by Bruno Brounch

What’s important is that, like in my studio, there’s no chairs, no chairs, no… No chairs. So nobody can come here and sit down and spend time here because there’s not a chair to sit down on. And I do this purposely because my studio is not a hangout spot. It’s like a laboratory. If you go to a laboratory or a dance company and they’re doing repetitions, it’s just you and the choreographer. And it’s the same thing. It’s just me in front of the painting. So I try to minimize the distractions and create a space where I’m that kid before, that’s bored on Friday nights, and he’s painting in his place, even though he has 10 billion things to do.

AK: And that makes so much sense because your paintings are so high energy.

JonOne: Yeah.

AK: Is that kind of what they’re about?

JonOne: I mean, in a way, yeah, it is. Because it’s about like… I wouldn’t say about that. But I try to live fast paced. I try to live an exciting life, you know, a fulfilling life. So then I try to express that in my canvas; live life to your fullest. So that’s what I’m trying to do.

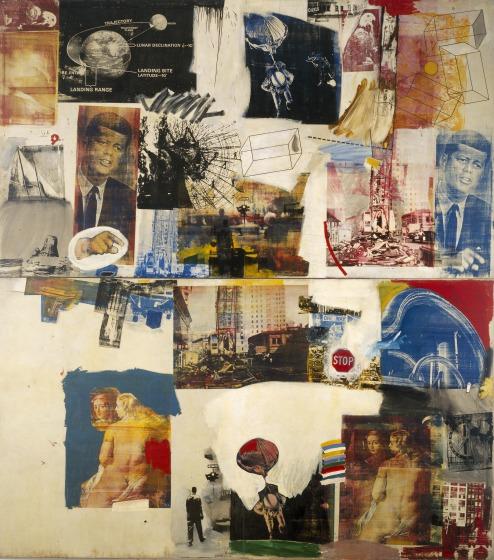

JonOne

Photo by Gwen Le Bras

AK: Yeah, I think that definitely comes across. You just mentioned that you were jumping around quite a bit– you’re in South Africa, you’re in Bangkok… Is there a specific city or show that you’ve felt particularly passionate about?

JonOne: No, no, not really. I mean, I’m always working on new shows, so I’m always excited for the next show that I’m about to do because I like to see my work evolving. So I think that’s really important about my work; it doesn’t really stay still, it goes all over the place. And that’s what motivates me the most is working on new projects. Like on the third of May, I’m supposed to go to the south of France. And I’m preparing a show that’s going to be… most likely in a year from now. And that show will consist of… doing the show in an abandoned church. And then from there, I’m going to paint a wall– I’ll do a big wall that’s like five stories up. So, I go on the third of May to meet the mayor of the city and things like that. So there’s always an agenda coming up.

AK: That’s really exciting. So you’re always looking towards the next thing?

JonOne: Yeah. But my dream is to do something in the states. Yeah, I would love to do something in the States. I’d like to do a comeback. You know, I never did a show in the States. I would love to do something there.

AK: Yeah, that would be great. I mean, always looking towards the next thing, I feel like that’s why your career as an artist has been such a marathon.

JonOne: Yeah, it has. It’s been a marathon.

Continue to Part 3

An Interview with JonOne (Part 2) Read More »

Artist Profile, Interview