How To Look At Art: Visual Analysis

Alex Katz, Homage to Monet, 2009, via Andrea Rossetti, 2016

In the “How To Look At Art” series, Alexandra Kosloski guides readers through the multifaceted journey of art appreciation, fostering a deeper understanding of the emotions and stories woven within the work.

“Fundamentals are the building blocks of fun”

Mikhail Baryshnikov

To begin to understand a work of art, it helps to know any context you can, including the artist’s name, the title of the artwork and the year it was created. This information is often provided, which is useful in considering the historical context, like why the artwork was created, who it was created for, and what movement it was a part of. These details can lay the groundwork for how to look at art. For example, the identity of the artist, or the era they are from may have a large impact on the meaning of their work. Sometimes I look for this information first, and sometimes I look for it last so I can look at the artwork without any preconceived notions. The more artwork you look at, the more you’ll begin to recognize automatically, like the style of a specific movement.

Look at the work and think about what you see. Also, think about what you don’t see. Try to look at art without immediately projecting your feelings or interpretation onto it. It may not be what it first looks like. Meaning can come to you very softly and slowly, you don’t have to rush to that point. First, observe the content– who or what is on the canvas and how is it presented? Notice all of its parts. Then consider how the artist manipulated the content and what they might be trying to communicate through it.

Keep an open mind. You should always assume that the artist meant to make the work look that way. If the painting looks weird, the artist wanted it to look weird. It’s not every artist’s goal to make a painting look representational or naturalistic.

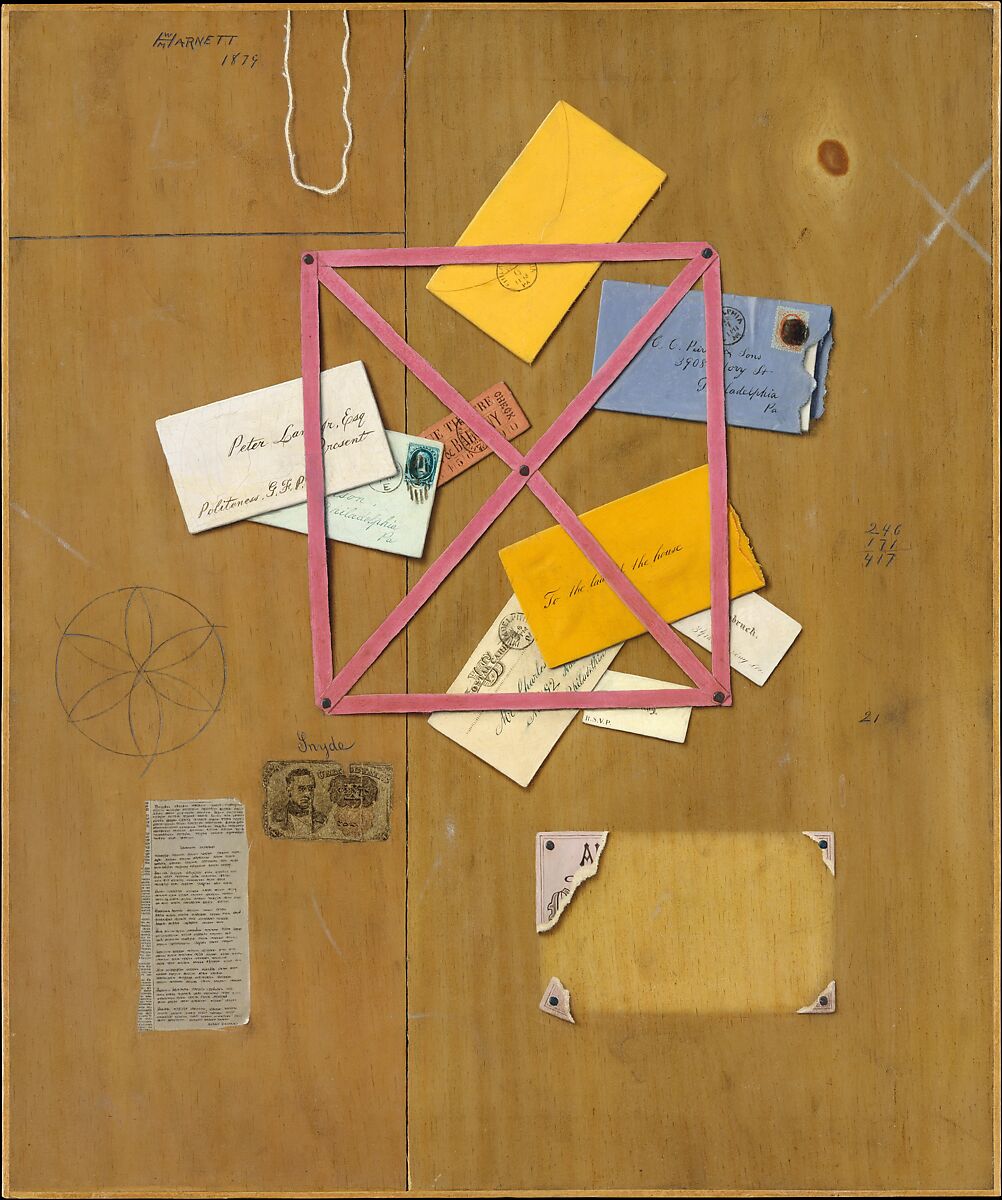

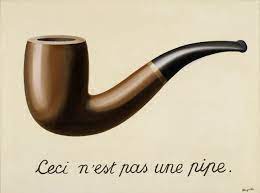

Rene Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1929, via MoMA

It’s a matter of style. Style can be dependent on the individual or the culture. Sometimes art is idealized, meaning it looks somehow more perfect than reality. Sometimes, art is expressionist, which usually looks a little chaotic and wild, and is meant to communicate emotion. Sometimes art is entirely abstract and is only expressive marks or random pieces. Don’t assume the artist didn’t have the skill to make art lifelike, beautiful, or the way you think it should look. That’s irrelevant. If you’re focused on what you think it should be, you’ll miss out on what is actually there.

Jamie Nares, Back Then, 2021

Then, try to use your observation to piece together what is being depicted. Consider the figures and what they represent, and if there is a narrative or theme being portrayed. Make connections to what you already know. If the work is abstract, observe the marks made by the artist. What is the overall mood of the artwork? How does it make you feel?

In Part 2, we continue into a more detailed analysis of art.

Continue to Part 2

How To Look At Art: Visual Analysis Read More »

Editorial