NYC Parks: FSG Park (Part 4)

Keo and Kanami Kusajima at FSG Park, July 2023

First Street Green Park opened in 2008, sits between Houston and E 1st street, and had formerly been an empty lot between two buildings. Today, it is a site that highlights the best street art of the moment, and brings visitors together with murals, music, community and cultural events.

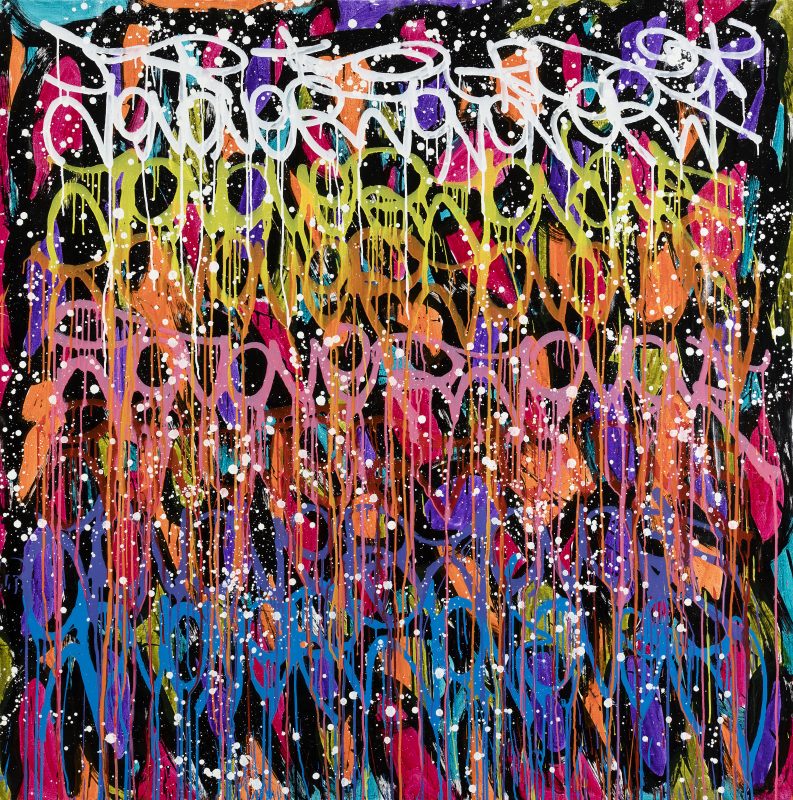

Art by Trasheer at FSG Park, July 2023

Like a gallery, the art changes regularly, and FSG Park has democratic approach. It holds open calls for art, but also features some of the most notable muralists, and is proud to include artists from all over the world. The Trops has collaborated with FSG Park at Keeping The Faith and Above Fresh Air, sharing a goal of community participation through the arts.

Work in Progress at FSG Park, July 2023

The appeal of FSG Park is in its ephemeral nature but unchanging mission. Visitors can always depend on being impressed by new graffiti, live music, performance, and good energy. FSG is for everyone. In this way, it’s a true manifestation of New York City street arts and culture. It brings out all of the best parts of the city– art, culture, style, diversity, charisma, collaboration– and shares them on one lot in The Lower East Side.

Art by KEO at FSG Park, July 2023

The Trops spoke with Anthony Bowman, Park Administrator, who shared some history of the park.

Video by Avery Walker

Shop our “Train Writers” collection, featuring artwork from FSG Park.

NYC Parks: FSG Park (Part 4) Read More »

Public Art