NM: Maybe art’s not about the individual, it’s about the idea being reified.

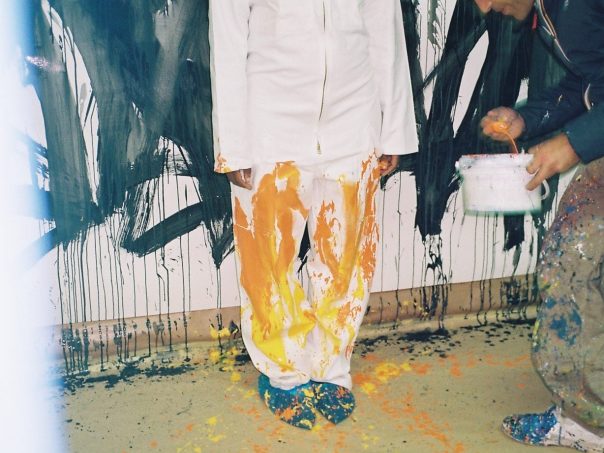

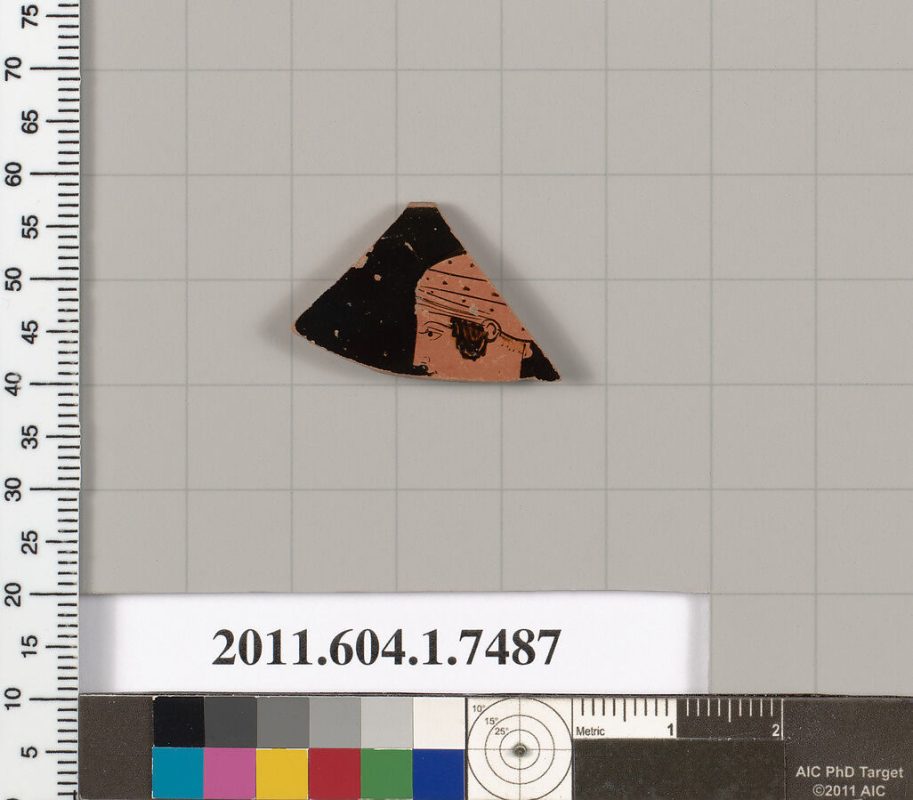

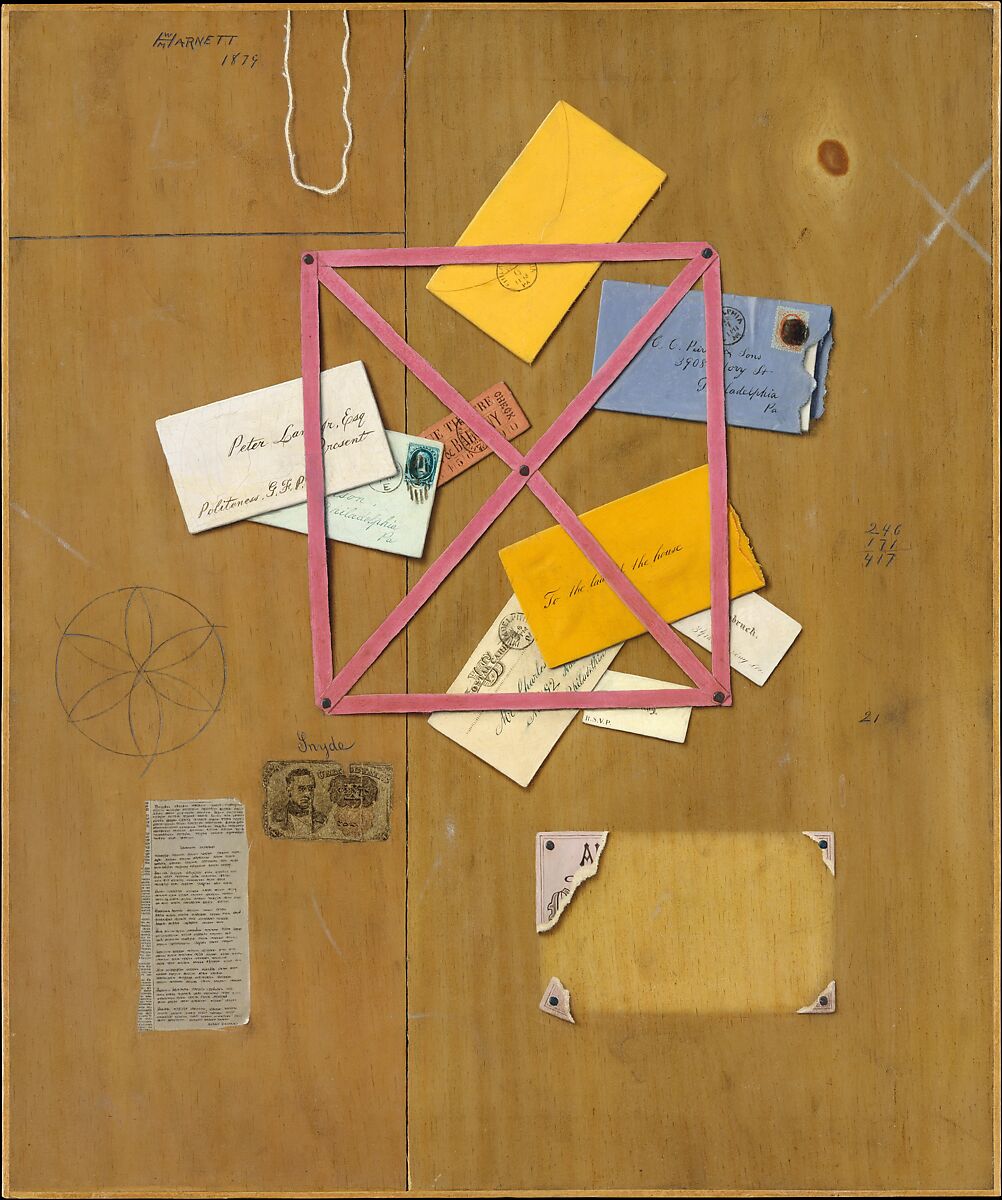

Barron Claiborne: It’s about everything. I’m not saying art should be anything, it’s whatever it is. All I’m saying, I care a little bit more if you painted the painting, rather than hiring someone else to paint the painting. That’s what’s happening. Artists that aren’t making their own work. It’s not like that didn’t exist. Vermeer and all those guys had 20 interns, just like people do now. When you look at most of the old paintings, tons of them, everybody’s left-handed, because they use the fucking camera obscura to trace. The animals or the monkeys in the painting are left-handed. But they’ll still deny that they used a camera obscura. But most people aren’t left-handed. How the fuck is everybody left-handed in a bunch of paintings?

NM: Durer made those engravings showing the camera obscura. Some artists acknowledged it.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, of course. In art school, I mean. Everybody creates their own mythology. So, you know, you look at somebody like Gaugin’s paintings… but his life was fucking miserable as fuck, dude.

NM: He was fucked up.

Barron Claiborne: He was fucked up. Spreading diseases and shit.

NM: Child brides and all that.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, they didn’t like him. He was hated by the French. And after a while, he was hated by the native people also, because, well, he was giving everybody syphilis, but also because he was poor and a crazy dude. It’s crazy. He had a fucking miserable life. Everybody hated him. Yeah, well, the French hated them because he hung out with the native people, and then the native people started hating him when he was spreading fucking venereal disease everywhere. He was ill all the time, he didn’t have food, like it was fucking crazy.

NM: We’ve been talking about painters. What’s the job of the photographer?

Barron Claiborne: To get the best image possible.

NM: Okay, I like that. Is that an objective thing?

Barron Claiborne: No, subjective. Each person, subjective to each artist.

NM: When you approach your work, when you’re taking a photo, what has to happen for you to be satisfied?

Barron Claiborne: I usually want it to be beautiful. Whatever that is to me, that’s the thing. I always want my photos to look timeless, so you don’t know when they were taken.

NM: Your photos do look timeless.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, because I really like history. I like the fact that you can’t tell –

NM: It could exist in any time.

Barron Claiborne: Right. It could be modern, old.

NM: Places, too. Any time or place.

Barron Claiborne: Exactly. I like those things, but I really like beauty. More than anything.

NM: Me too. I love that you said this, because artists never say this, or are just not being honest. It first needs to be beautiful! I must want to go up to it, right? That’s my first criteria for looking at work.

Barron Claiborne: Right, right. It’s not for all artists.

NM: No, but I love that answer. I think that’s genuinely the most important thing. And it’s not superficial. There’s a science to it, I think.

Barron Claiborne: Oh, sure!

NM: Like I think beauty is kind of, maybe, objective.

Barron Claiborne: I think if you make a system, you know, you make or do certain things all the time, you can expect certain results. There’s a science to it. And it’s on every level. If there’s a bunch of gardeners and my garden is far more beautiful than theirs, then I’m the master, and they’re the students. It’s on every level. There are scientists doing physics experiments, and there are basketball players that are literally using physics to play basketball. But people don’t think of that. They’re experts on physics, but you just don’t think of it.

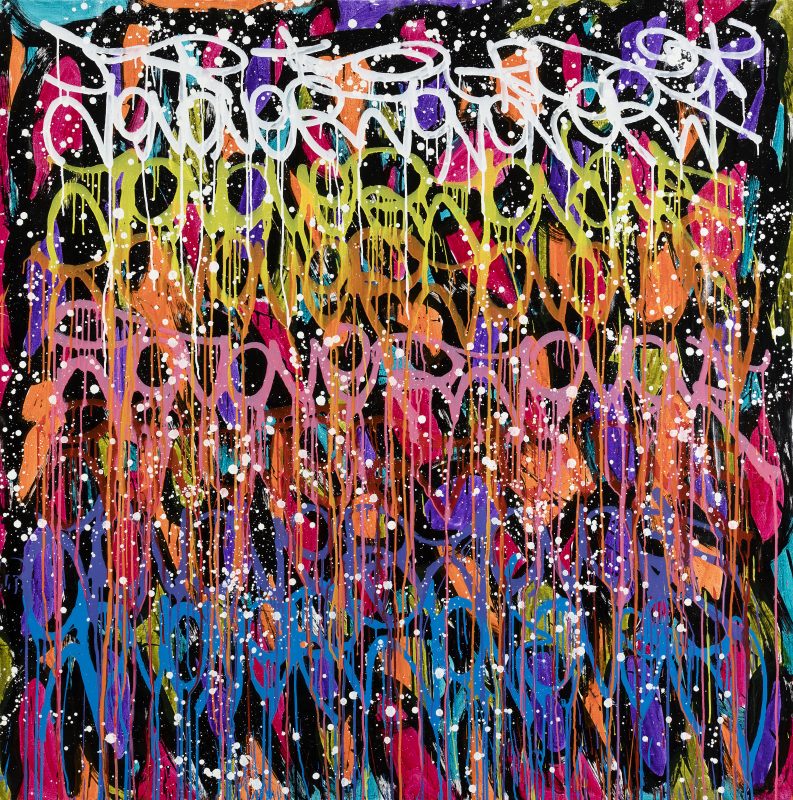

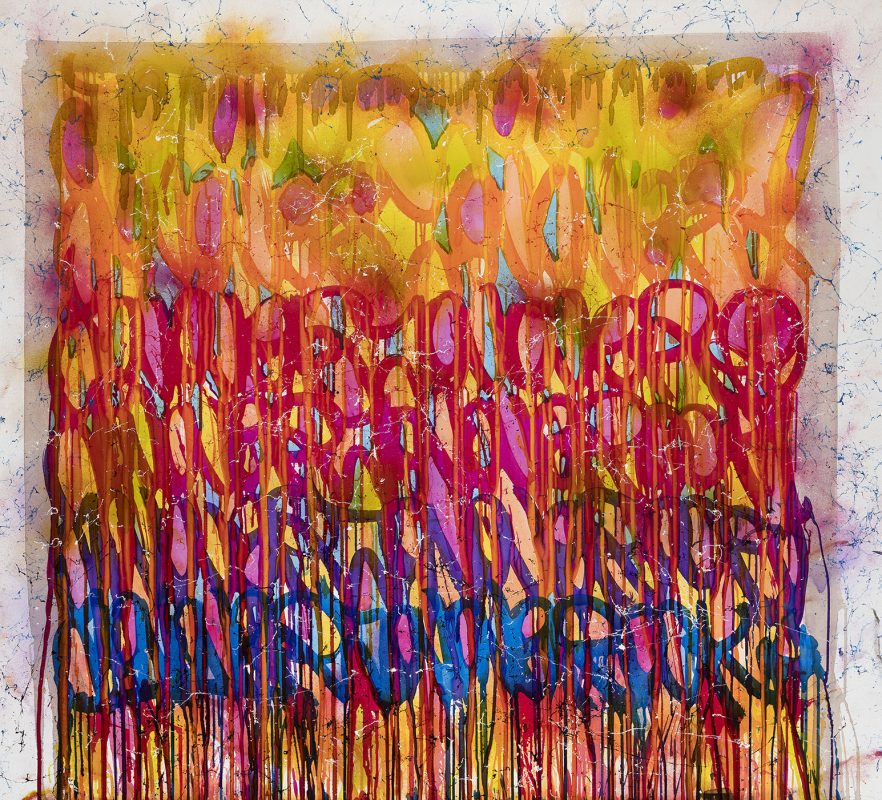

NM: Yes, but beauty specifically. It’s literally a science. Color theory, for example. These two colors work or don’t work because it’s a science, not because someone decided blue and orange are randomly complementary.

Barron Claiborne: Definitely. But then there’s some cultures that will go the opposite.

NM: What do you mean?

Barron Claiborne: In some cultures, red is a very good color, but then in other cultures they avoid using red at all. You always have both sides. So is it a science?

NM: Yeah, if you take out the idea of good and bad, etc. Purple and yellow will always be complementary.

Barron Claiborne: Sure, yeah. But it’s so funny that different colors, depending on what culture you come from, mean completely different things.

NM: Absolutely. I was reading this Nabokov interview and he talks about how he sees letters in colors.

Barron Claiborne: Oh yeah, that’s a thing, what’s it called? Synesthesia, some shit like that?

NM: Yes. He said, “N is obviously yellow, and H is obviously green,” stuff like that.

Barron Claiborne: Well, just like colorblind people. So now they have these glasses that can correct your color blindness, so people buy them as gifts for colorblind people. You should see the reaction. You know, colorblind people see green as red, shit like that. That’s why they use them in war to spot tanks and shit. Because they don’t see green as green. They see different things so they can spot things that a normal person can’t see. They use them in planes to see enemy tanks and shit. But the thing is, some people smell colors, some people see colors, some people see them as numbers. There are all kinds of weird synesthesia shit. I’ve read a book on that shit. It’s so fucking weird. Some people see letters as colors.

NM: Yeah, sounds, even.

Barron Claiborne: Everything. There are all different kinds of it.

NM: You said growing up, you didn’t really care about credit, or your name being attached to your work.

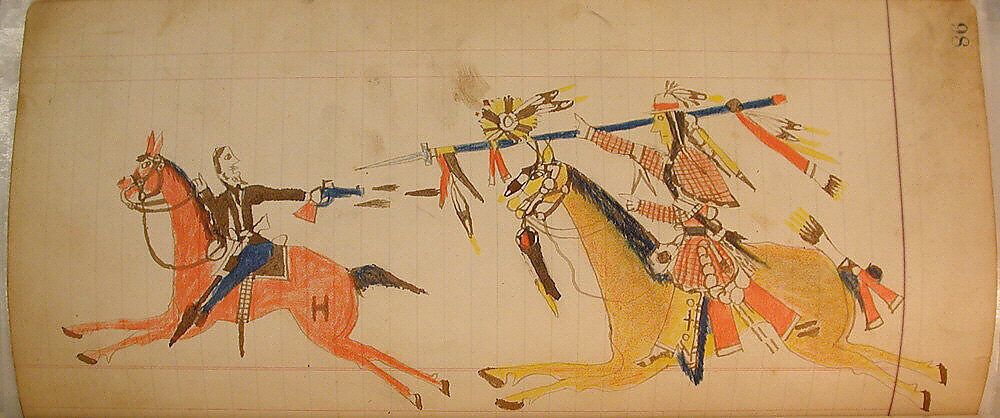

Barron Claiborne: I mean, some of the greatest art in the world, nobody knows who made it. Nobody has any idea. They didn’t sign it. But no, I mean, you care a little bit. Everybody has an ego. When people are telling me they like my photos, of course I like to hear it.

NM: I think to be an artist you need a certain amount of ego. You feel you have something to say, to show.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I think so. I mean, you’re making something. The natural thing would be because you want people to see it. Just because people deny it doesn’t mean it’s not true. Because people often say stuff like that, that they don’t care, but you kind of have to. But everybody has a shtick. It doesn’t matter how serious the person is, everyone has their shtick. A lot of artists are just con artists, really.

NM: Artists are lying to you and saying it’s the truth.

Barron Claiborne: Mm-hmm. That’s right. But you need artists because everybody is kind of one. I’m always shocked at how much photos mean to people when they come up and tell me. It freaks me out when people come and tell me they cry, when they come in and buy a Biggie print from me. They cry and shit like that, I’m like, what the fuck? At first, I used to think it was weird, and now I’m like, well, if it means that much to the person, it must mean something.

NM: Were you just going to say you think everyone’s an artist? Because I don’t.

Barron Claiborne: No, I don’t think that. I think you’re an artist at something. I don’t know about everyone.

NM: I think there’s a difference between artists and like, “makers,” for lack of a better word. There are people who make things, and there are artists.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, but I think those people are also artists. If a guy is a gardener, right, and he makes it look beautiful, he’s an artist. He’s an artist at that.

NM: Oh, totally. That’s an artist. Someone who wakes up every day and does that, that’s their practice. Maybe I just mean there’s a difference between “making art,” and being an artist.

Barron Claiborne: Right, right. Well, I think everyone has it in them.

NM: Yeah… maybe. Maybe they don’t.

Barron Claiborne: Well yeah, some people probably don’t. There are some people probably who fucking hate art. You meet people who hate music. I’ve met people who don’t have any music in their house, they don’t have a stereo. I’ve been in houses where people are making millions of dollars. And there’s no stereo, there’s no music in their house anywhere.

NM: It’s insane. People also don’t have books. The biggest red flag.

Barron Claiborne: Oh, tons of people don’t have books. Or when people have a TV in every single room, including the bathrooms and the kitchen. I was in this guy’s house; he had a television in every single room. And in the garage. In the bathroom. He even had a TV in his kitchen closet that he could pull out and watch in the kitchen. It was fucking weird. And his house was huge. There was a television in every single room. It was fucking weird. I was like, “Wow, dude, you watch TV a lot.”

NM: Were your parents strict with TV?

Barron Claiborne: Dude, I didn’t give a fuck about TV. I was a kid. We were outside playing football and all kinds of stuff, doing shit that we were supposed to do, running around Boston. The only TV I would watch would be if I woke up on Saturday morning and watched cartoons or like sporting events, the Superbowl and shit like that. Other than that, I don’t give a fuck about TV. We never sat down and watched TV like that. And Americans, when I was a kid, the TV obsession didn’t exist. Americans watched TV, but not like they do now. I mean, it’s insane. But, yeah, give me a break. Americans never even talked about celebrities. I never heard my mother ever say anything about a fucking celebrity in my entire life. You know, they never talked about it. They like the music and shit like that, but they never talked about it. Like they listen to Stevie Wonder. Nobody gave a fuck about what Stevie Wonder was wearing or doing. Nobody cared.

NM: Well, I feel like culture has shifted from exclusivity and “you wish you could be like us”–

Barron Claiborne: To no one is special.

NM: Yes, no one is special, but even “buy this and you can be like me.”

Barron Claiborne: Yeah. No one’s special. So now you have to act like beauty doesn’t exist. No woman is prettier than the other, they’re all tens… it’s fucking insanity. Basically. You still have value, but everybody’s not physically beautiful. I mean, so what! Everybody’s not smart. Everybody doesn’t care about their clothing. Everybody doesn’t– it’s not like that. It doesn’t matter. Because everybody has their own thing. Do your thing and let other people do theirs, unless they’re trying to stop you from doing yours. If they’re not harming you, I don’t give a fuck what you do. You want to have sex with goats? Just don’t fuck my goat.

NM: I guess that’s one way to put it.

Barron Claiborne: You know, fuck your own goat! There are things people do all the time that I don’t like. But who am I to judge other people?

NM: I think that’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned… that once you start to judge, it means you don’t understand. You’ve lost the ability to really think about something.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I agree. I think the worst thing is to judge people. I think now, the way things are, it’s like people believe that constantly judging is performing a public service or some shit. They act like they’re spiritual, but then all you’re doing is constantly talking about how you’re better than the other people. What the fuck is that shit? And that’s what a lot of it is. This “justified” criticism. But then as soon as somebody criticizes you, you lose your fucking mind and call them all kinds of names. But you’re doing the exact same thing. And you think your cause is just.

NM: It’s funny too because all the criticism isn’t actual criticism. It’s all judgements, like we were saying. I think we could use young art critics. There’s a serious lack of them. You know, people who are thinking. But now we just have everyone spewing out bullshit.

Barron Claiborne: Social media, too. It’s brown nosing. You’re just saying whatever. Whatever everyone else is going along with.