I worked in that studio and I made friends with other assistants, and once in a while they would take me out with them to Studio 54, and the floodgates opened up. I told a friend that I would go to Italy with him, because somebody wanted to work with him there. We planned a trip to Milan, and I gave notice at my job and saved 1500 dollars, which was a shitload of money for me. And the night before, he bailed on me. I didn’t know what to do, so I just said, “Fuck it, I’ll go”, and I went on my own. I didn’t even know where the magazines were. I didn’t know of any hotels. I got a room with a neon sign that flashed and buzzed, like in a film noir. I put my suitcase down and didn’t even open it. I couldn’t even go home.

I ordered a big pitcher of beer, and I got myself shitfaced, and who walks by is a photographer, who I had assisted. He’s like, “Why are you in that hotel? Stay in my hotel, with all the models and the young photographers.” He goes, “I’m going to Portofino tomorrow with my girlfriend for the weekend. Why don’t you come with us?” I was like, “Oh, God, thank you.”

I took my luggage over there, and went to Portofino. He gave me the name of all the agencies, all the magazines and everything I needed to know. It was a godsend. I checked into the hotel on Sunday night, and Monday was the next day. And the photographer said to me, “Look, there’s no work. I’ve been here for three months. I have to go back, there’s nothing happening.” I said to myself, I’ll take my shitty portfolio and go to Italian Vogue. And when they say no, I’ll get on the train and go visit family.

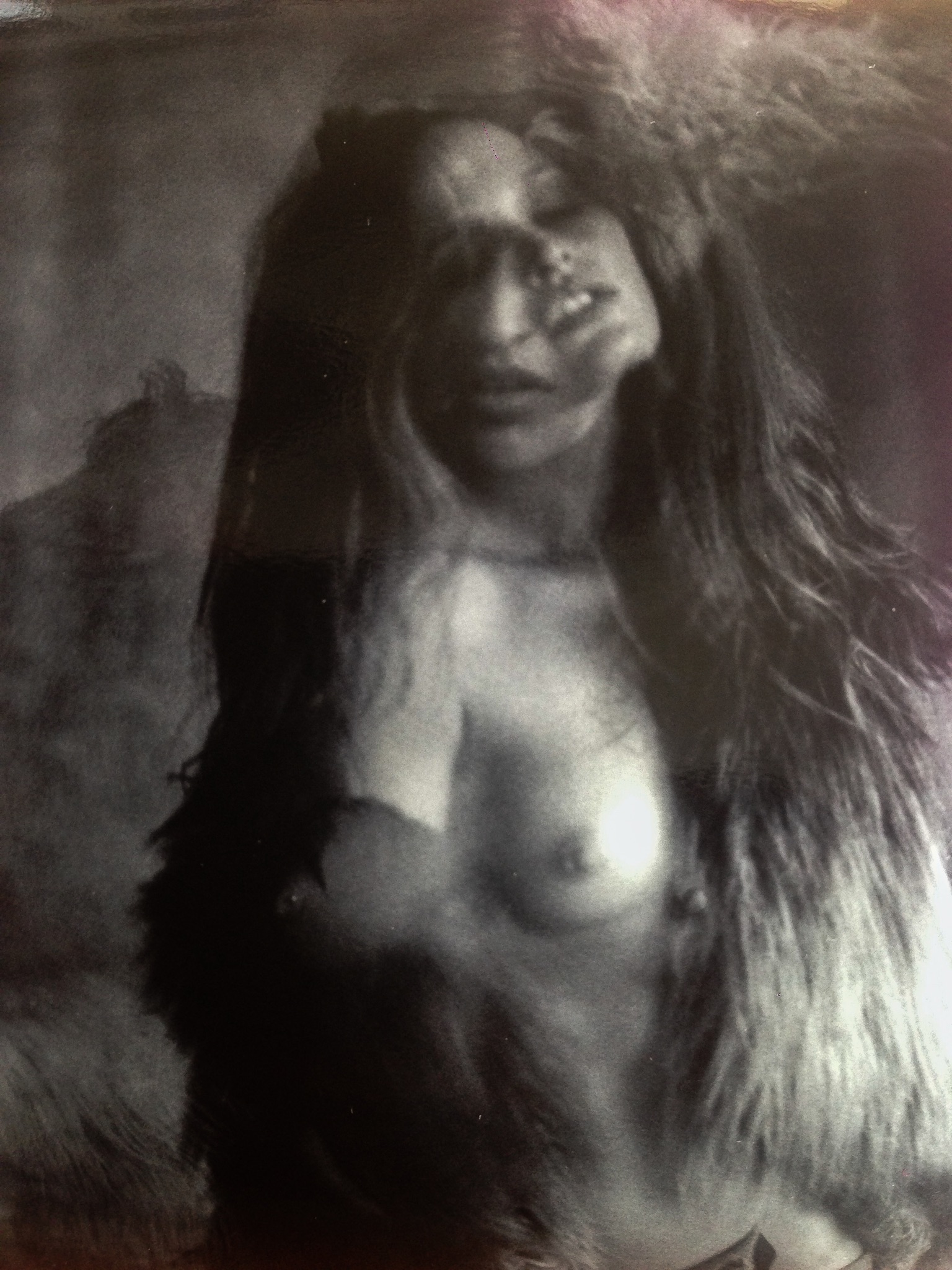

I go to Italian Vogue and they let me wait for the art director. He looked at the portfolio– the whales, the drawings, ten pictures that looked like ten different photographers. And then he goes, “Wait here. I’m going to wait for the beauty editor to come”. She came and they talked to each other, this and that, and they gave me two double pages to do nudes for Italian Vogue Beauty. So on my first day there, I got that job. Because they were creative, they saw nude drawings that I did, they saw I could draw a sensual line, they saw the whales that were sensual, and they saw in the ten different photographs that I could light.