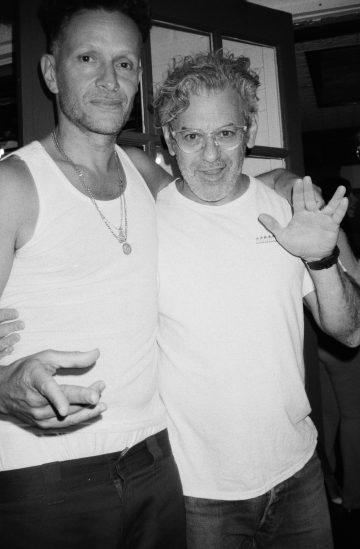

An Interview with David Aaron Greenberg (Part 1)

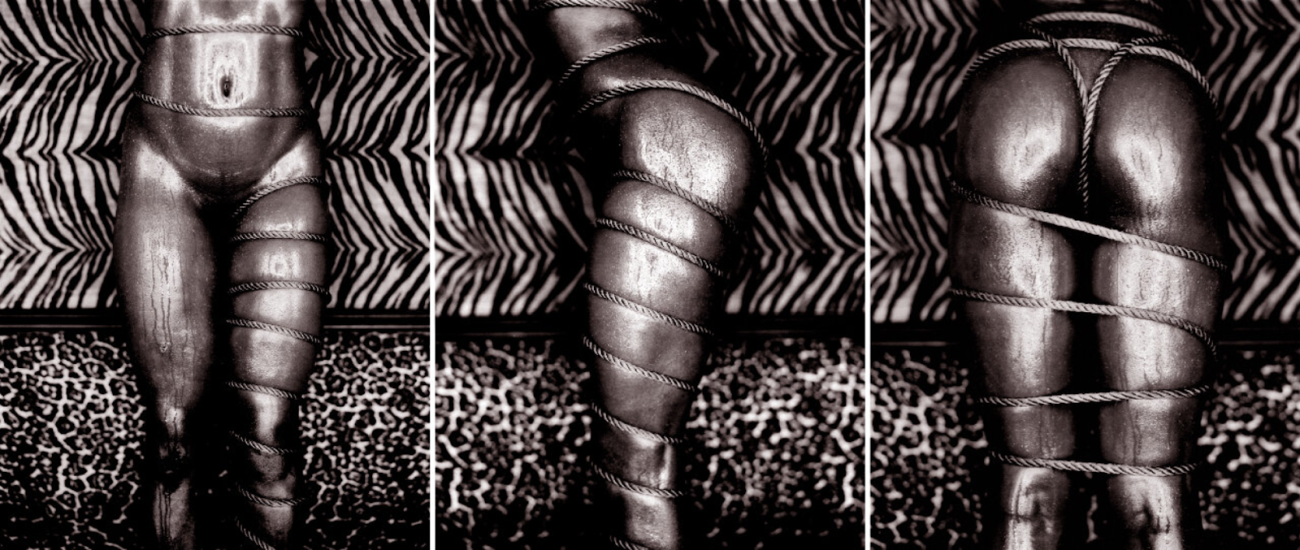

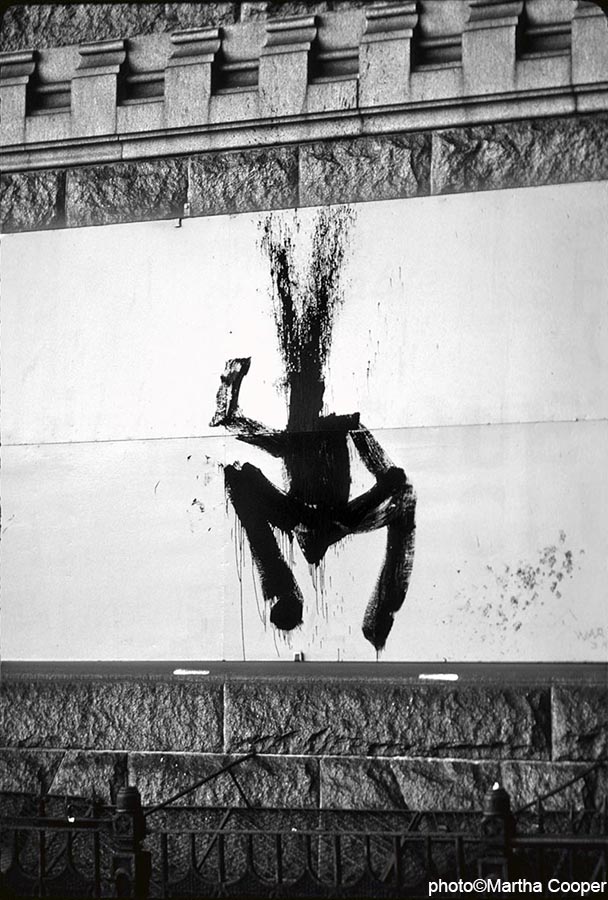

The artist’s studio

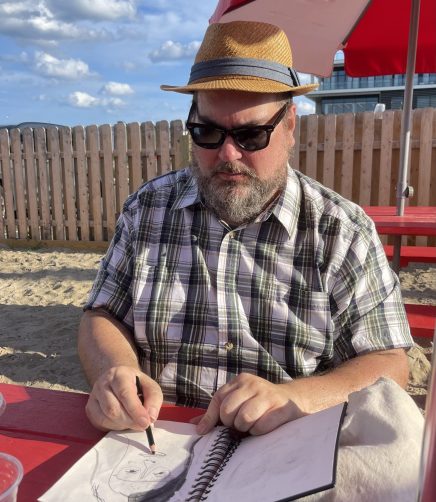

Photo courtesy of David Aaron Greenberg

David Aaron Greenberg is an artist who uses multiple modes of expression. His work has been exhibited in various New York City galleries and is in the permanent collection at Stanford University. His critical writing has appeared in Parkett, The Fader, Art in America and Whitehot Magazine. Along with producer David Sisko, he co-founded Disco Pusher, a New York City songwriting and recording duo. Greenberg graduated from Rutgers University, Phi Beta Kappa. He lives in New Jersey and sometimes New York City.

In part 1 of their 3 part interview, Alexandra Kosloski and David Aaron Greenberg discuss his early approach to painting and his love for poetry.

David Aaron Greenberg: In the last three years, I’ve kept my guitar out of my studio. That was a big, important thing for me to do, to not have the guitar in the painting studio.

AK: Why?

David Aaron Greenberg: I finally found that it wasn’t appropriate. There’s no place for the guitar in there, just like there’s no place for an easel in the recording studio. I needed to do that in order to keep my head together because I’m not 25 anymore and living at the Chelsea Hotel. I’ve got to separate things. Keeps the mental craziness in my head in check. Do you mind if I draw you while we do this?

AK: I don’t mind.

David Aaron Greenberg: It’s easier for me.

AK: So you’re an interdisciplinary artist including painting, music, writing… Anything else?.

David Aaron Greenberg: “Include.” No, I just do them. I include everybody. All inclusive. I’m not exclusive. I cheat on myself. I’m in an open relationship with myself.

AK: But do they overlap at all? Do they inspire each other?

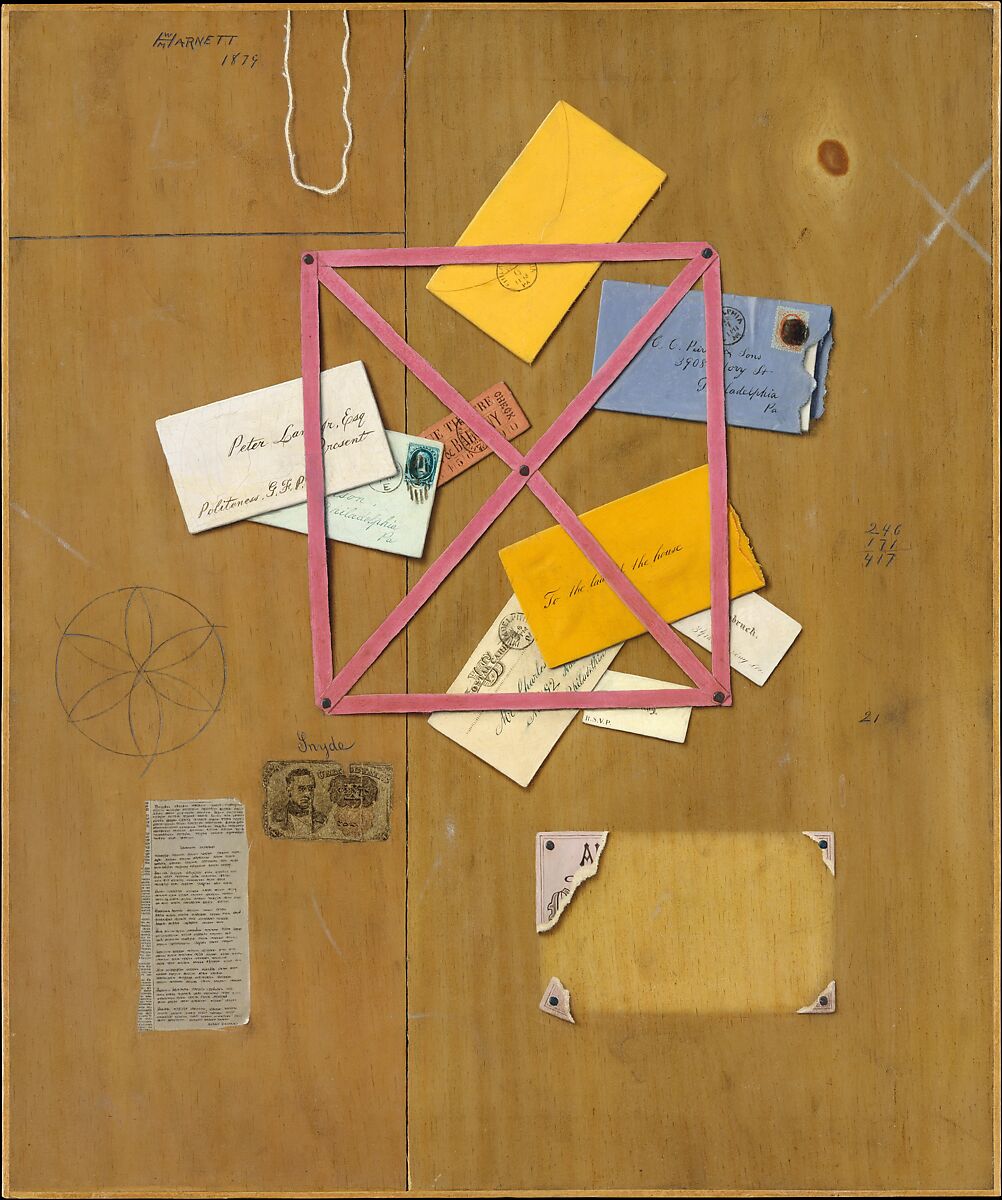

David Aaron Greenberg: I have a moleskine matte black sketchbook without lines. It’s like the most basic, nondescript moleskin notebook that you can have and within that is everything. I’ve got stacks of them from the years. If I want to make a drawing into a painting, I pull out the drawings, stick it on the wall next to the painting and go, “Okay, what else do I do?”. Music– if I need some lyrics, I steal from my poems. I steal all the best lines from the poems and put them in. I steal from myself and throw them into songs.

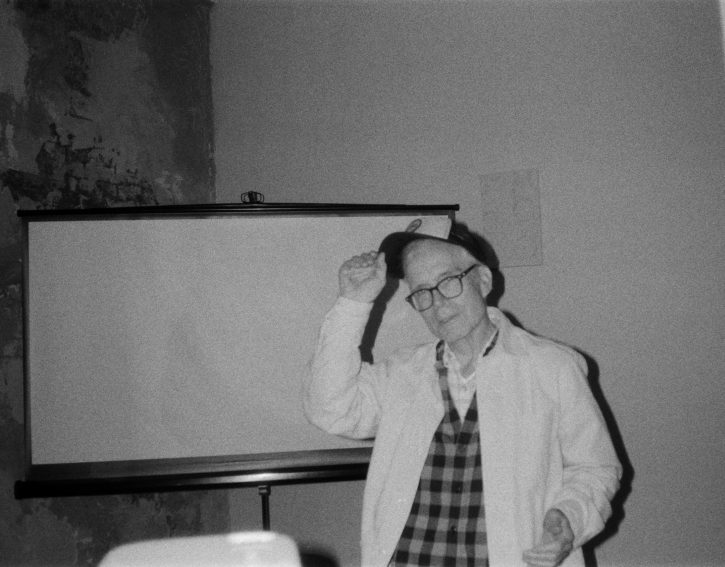

David Aaron Greenberg during the interview

AK: So you have this sketchbook which is basically a physical manifestation of all your inspiration.

David Aaron Greenberg: Yeah, but at the same time it’s like a shorthand to explain what I do. I mean, there’s other stuff I do, like I write essays and I write art criticism. So I just live my life. I don’t really know what I’m doing day to day, but it’s nice to have an excuse to pretend that I’m a normal person. So I try to keep studio hours Monday through Friday 1 to 4. Those are my office hours like I’m a psychiatrist. I might get there before one, and that’s a good day. I might get there after one, and it’s like I’m rushing around. I might not get there at all. But that’s the painting, you know? It took me my whole life to take myself seriously as a painter. I never did, unfortunately. Or not unfortunately, it was what it was.

AK: How did you first approach painting?

David Aaron Greenberg: I think I became a self-aware artist when I was 17 because I had been to Israel for the whole summer– 1988. And I had taken pictures, like you do as a tourist, and a Jew, and you’re in Israel. I didn’t take any pictures of people. I was not interested in people. I was interested in myself and my girlfriend who broke up with me the day before we were supposed to leave. And I had to be on the trip with her the whole time. So there’s misery for you. Yeah. And I had to watch her screw some guy and rub it in my face the whole time. Ah, the eighties. To be young and in a John Hughes film that didn’t exist.

So, the thing that made me aware was I don’t think I drew a picture when I was in Israel. I had a journal that I kept, and I was writing lyrics and diary entries and poems. When I got back from Israel, I had all these pictures and I did these giant watercolors. And then I was like, “Oh, I get it”. You come back to your studio with the source material. But I was still so much more interested in being a poet or a rock star. Then I was like, “Fuck it”. I loved painting but I would always do it in spurts. Like, I’d do a year’s worth of paintings in a weekend. But it took me my whole life to realize that I was painting those paintings in my mind and when I was taking photos as reference, and then I had to digest it. It took me a long time to realize that.

And I was around a lot of painters, and saw their practice, and I knew these things intellectually that, God, it’s just like a day to day job. You got to wake up, paint until you’re done, and then you go home. Yeah. Like a job. I was just holding on to this romantic notion that it was this inspired moment of creation and not, as de Kooning said, 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration. Yeah, which it is, pretty much. That 10% inspiration is what you work so hard to get. I wrote in a song, “Why do I work so hard to play?” Because you do. You work so hard just to be able to play. And then the worst is when you get there and everything’s great; the studio’s all ready to go, I have an hour, two, three hours to just paint. I even turn the music off. And then nothing happens. And then you feel horrible.

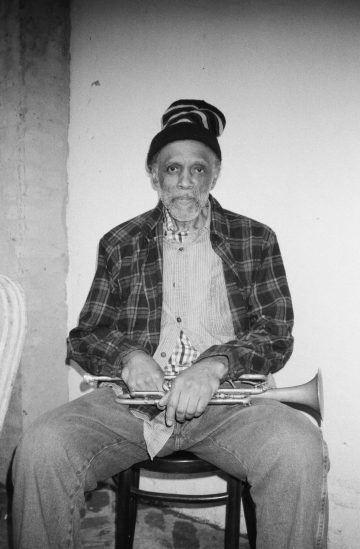

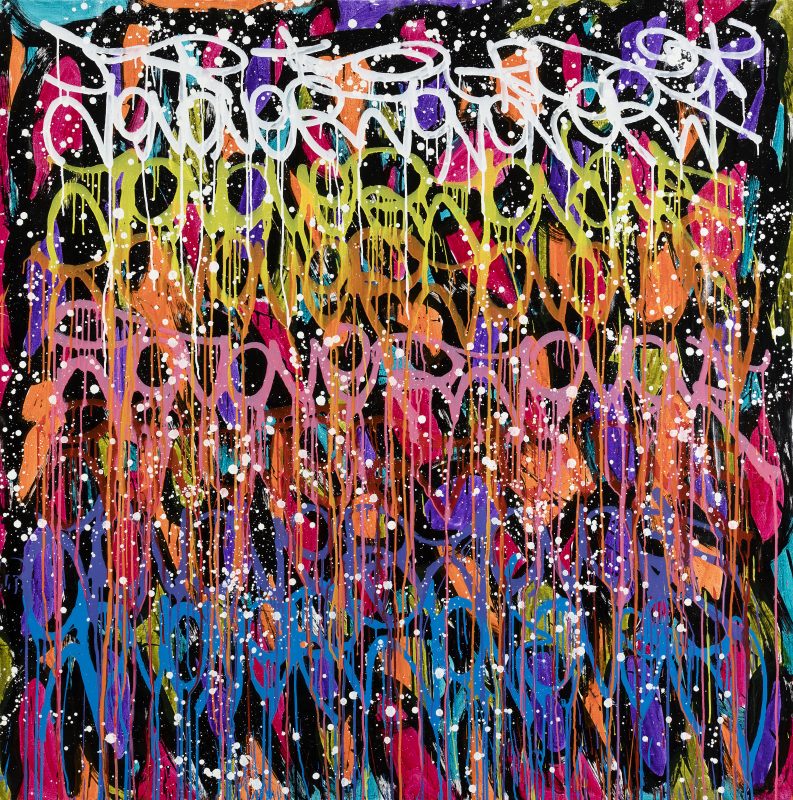

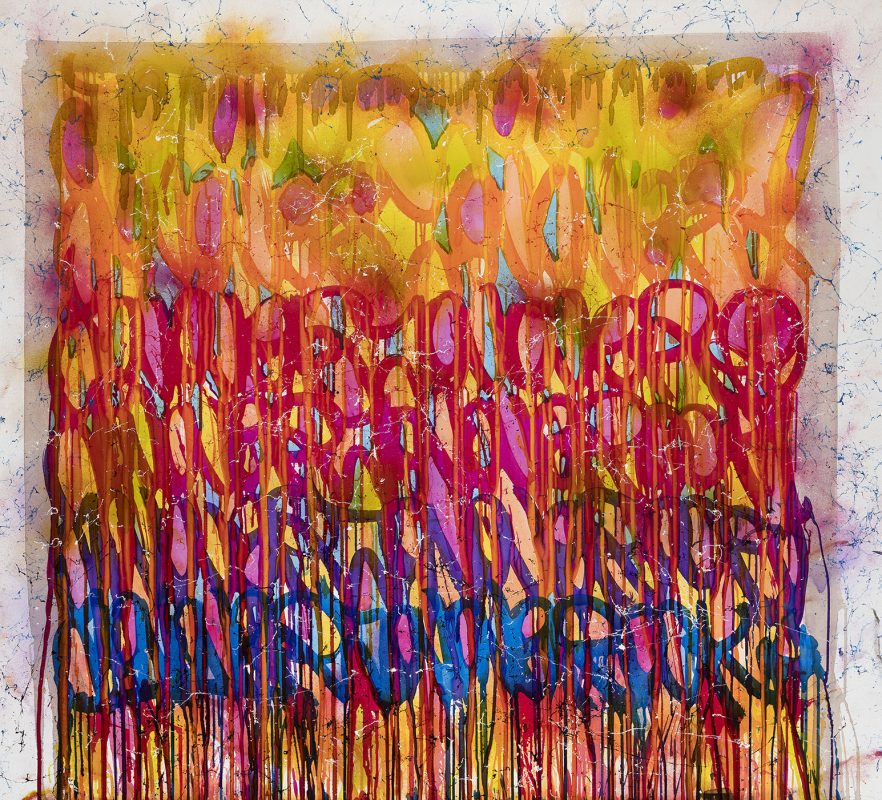

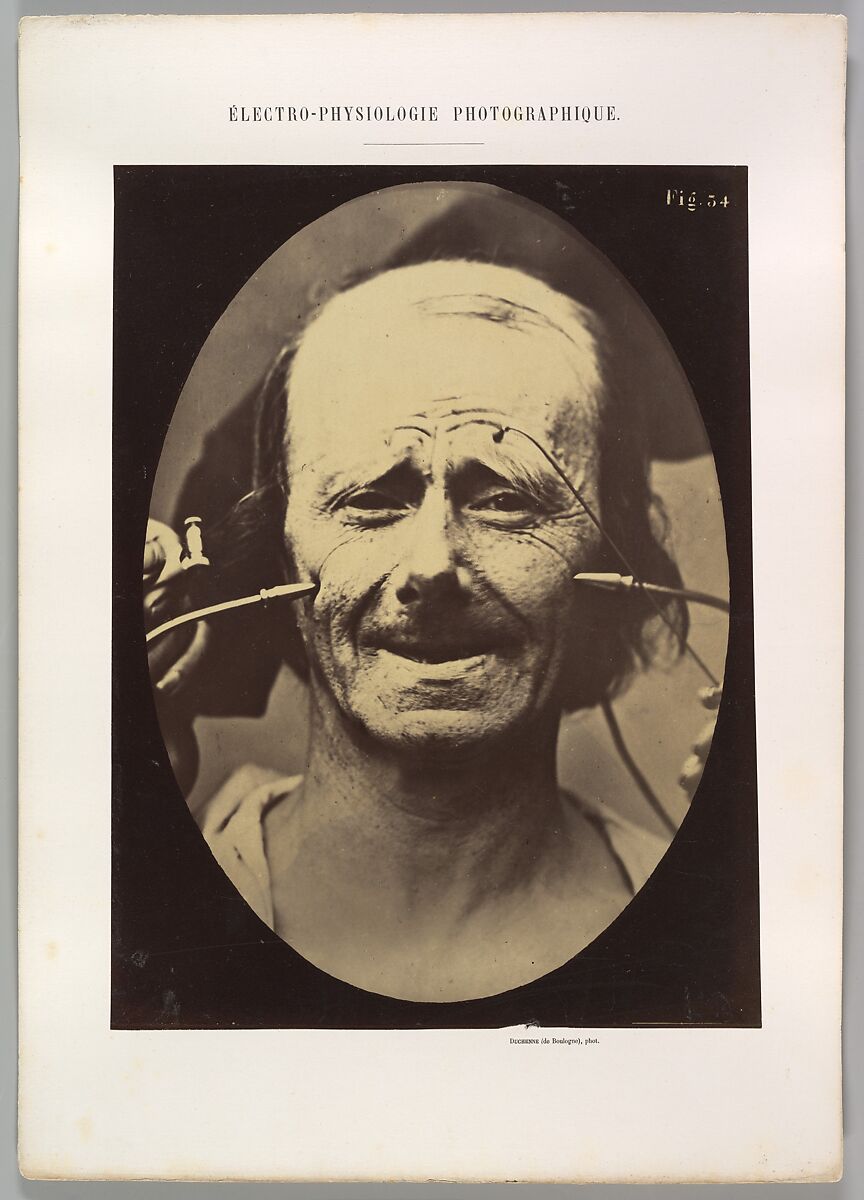

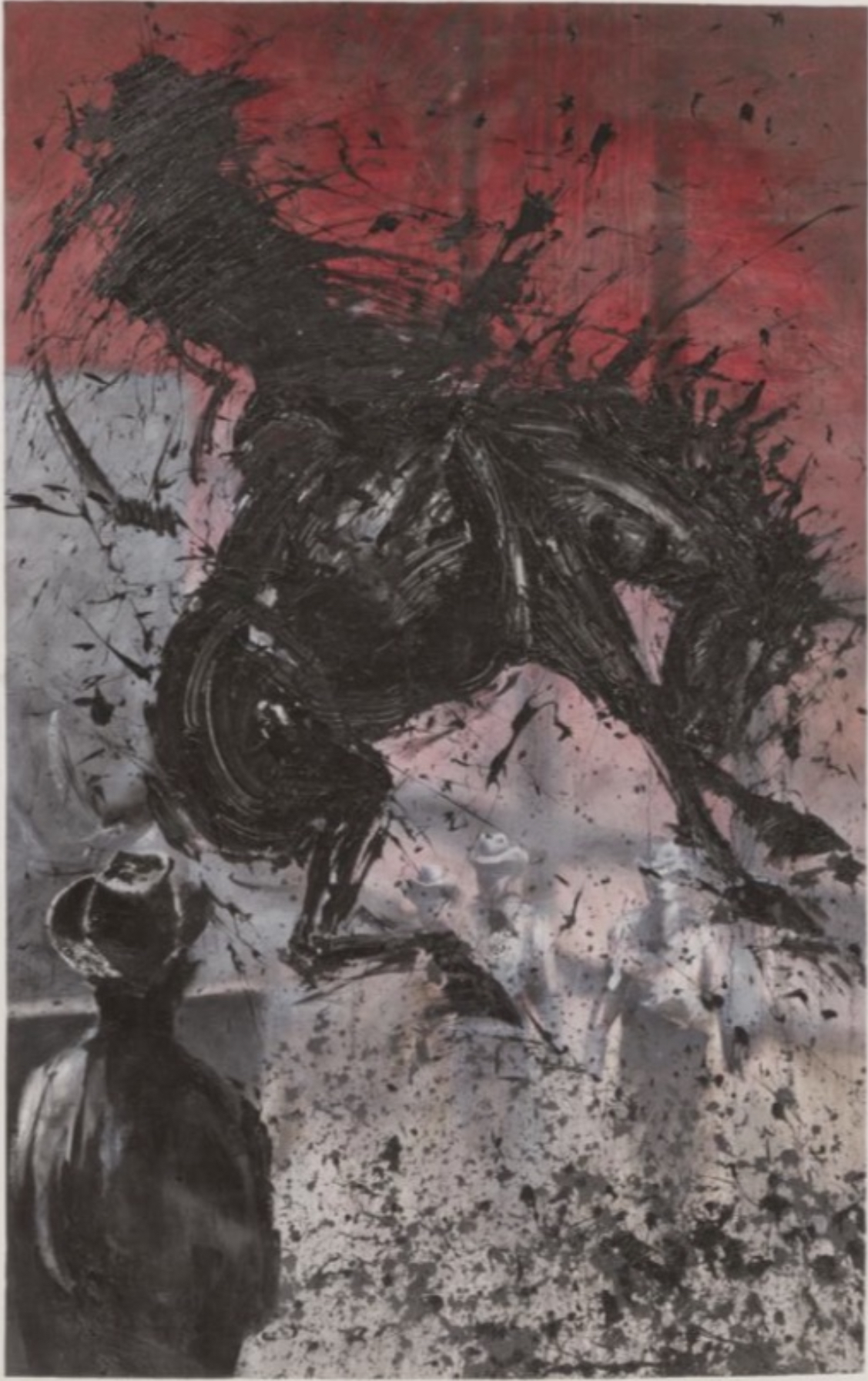

Installation shot of David Aaron Greenberg’s work at Eroica Variations

AK: What do you mean “nothing happens”?

David Aaron Greenberg: Literally, nothing happens. No inspiration, no nothing. I got nothing. That’s the worst, because it’s like, “Well, now what?” That’s why I like to have at least, like, three big ones and, like, twenty little ones going on all at the same time because at least then I have something to do. Because then it’s not that moment of like, “Here’s a blank canvas– start.”

AK: It’s hard sometimes.

David Aaron Greenberg: It’s not that it’s hard. It’s just that sometimes you’re paralyzed, and that’s why accidents are great. Like, literally, “Oh, shit. I dropped some paint on this. Well, that’s awesome. So let’s continue”. And that’s how I start all my paintings. This art dealer John Cheim told me at some point– just buy pre-stretched canvas that was already primed, stop with the raw canvas, enough already. And it freed me. Because he wasn’t an artist. He tried to be an artist and became an art dealer, you know, so a failed painter or whatever. He just said he realized that there was enough shit in the world that was better than his shit. So he’d much rather help people that were making good stuff, instead of making mediocre stuff. I don’t think that way. Maybe I’m just full of myself. I kind of have this theory that a painter, when they stand in front of a blank canvas, they have the history of the world and everything that came before, behind them. And it’s like, let’s dive into the abyss, because I know everything there is to know, because there’s not that much to know. You can just pick what you need to know. Etruscans, Middle Kingdom, Old Kingdom, line drawings, Coptic vases. Like, what are we going to do today?

AK: But that’s assuming that you have exposure to all that.

David Aaron Greenberg: Art history? Well, that’s the first step. Most artists don’t know their art history from anything. But that’s probably why I don’t know what I am. I’m an artist, a poet, singer, songwriter, visual artist, essayist. I mean, there’s so many labels. In the Renaissance they just said, “You’re an artist”, and you were expected to do all that other stuff. Yeah, Michelangelo wrote poems. Leonardo made scientific drawings and did dissections and no one said, “don’t do that”. It’s very American to say, stay in your lane.

AK: There’s more incentive to become a specialized artist and it’s the more popular method. So what motivates you to remain interdisciplinary? But I get the feeling you don’t like the word interdisciplinary.

David Aaron Greenberg: No, it’s fine. I didn’t want to use the word interdisciplinary because I find it unbearably hard to pronounce. I said that I use various modes of… Yeah, interdisciplinary. It sounds so formal and antiseptic.

AK: So why do you stay that way?

David Aaron Greenberg: Because as much as I try to just do one thing, I can’t help myself. I used to say for a long time, “Hi, I’m David Aaron Greenberg. I’m a recovering poet. It’s been 48 hours since my last poem.” I’ve tried to stop writing poems. I didn’t want to write. I didn’t want to be a poet. I kind of felt like I was obliged to be a poet by Allen Ginsberg who insisted upon it.

AK: Could you explain his influence on you?

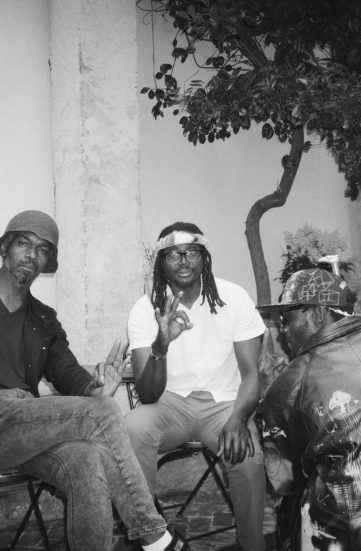

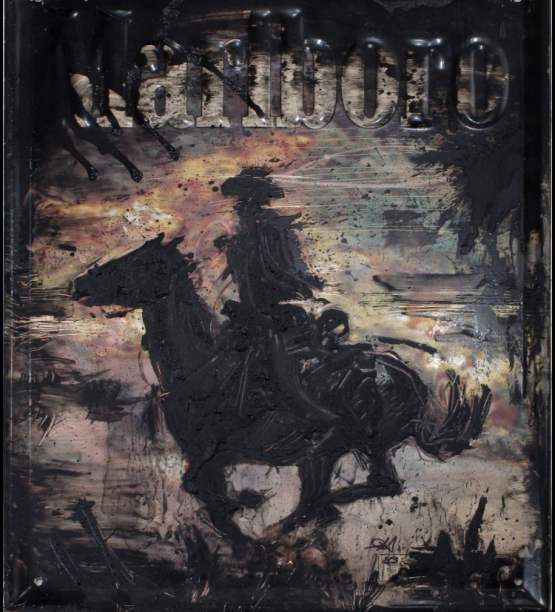

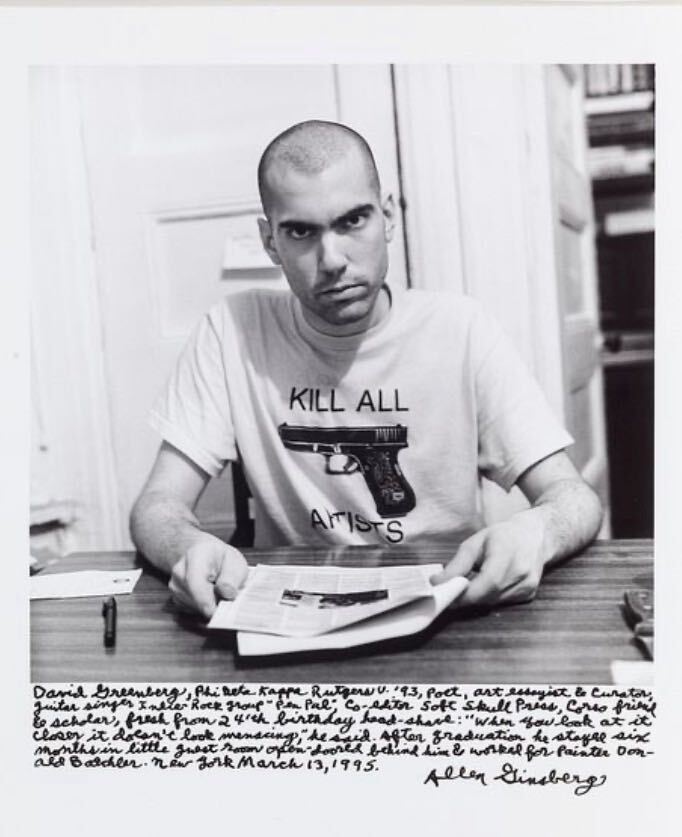

David Aaron Greenberg

Photo by Allen Ginsberg

Collection of National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

David Aaron Greenberg: Around 1987, I really found that I was like… I don’t want to say influenced. Inspired. I was profoundly connected to Walt Whitman. It was beyond just liking his poem or reading his poems. I felt connected to him in some way, and that brought up feelings of myself, my identity, my sexuality, my very existence, my everything, the universe, the cosmos. As he would say, “Do I contradict myself? Very well. I am vast, I contain multitudes”. And so anything that had to do with Walt Whitman, I was interested. So PBS had a Walt Whitman documentary. And in the documentary, there was Allen Ginsberg, poet, and the name sounded vaguely familiar. And he’s talking about what? Walt Whitman. And he seems to really be connected to him, too. Like, “Oh, wow, I’m not the only crazy who thinks that they know Walt Whitman”. And so I’m like, “Who’s this Allen Ginsberg dude?”. So I went to the library in East Brunswick, New Jersey, and I said, okay, Ginsberg poetry. And I took out whatever I could find. I opened it up and then I felt paranoid. So I went to the lake outside past the parking lot and I started reading them and it felt subversive. I shouldn’t be reading this like, is this illegal? I was hiding the book. I read a couple of short poems and I had this kind of deja vu into the future. Does that make sense?

AK: Like a premonition?

David Aaron Greenberg: Yeah, but how could you feel something that hadn’t happened? It was almost like it had already happened and I was going to relive it. And what I had was a visual of an old man in front of me, and me, carrying plastic bags from the grocery going up a staircase and helping him get up to the staircase. And then I felt this enormous sharp pain and heaviness on my chest, almost like heartache. And it wouldn’t go away. It didn’t leave me for days and then those days turned into years. And then about two and a half years later, I saw him read at the Continental Divide. He was singing Songs of Innocence and Experience that he had set to music. And then he read some poems. I don’t remember what the poems were, but he was singing. “Singing” really is an interesting thing to call it, but he was trying to sing and he had a guitar player with him. He was okay. And then I talked to him very briefly. He signed my copy of Howl. I sensed that there was something going on between the two of us. That was December, 1989. By December, 1990 I was on that same stage and I was playing guitar with him. And I gave him poems, and he read them and made corrections or suggestions. And then it was like I was writing poems to please him in a weird way. When I met the poet Gregory Corso, who I also admired, he pulled me aside and said, “Don’t let that man fuck with your poetry”.

AK: Why? Because you wanted to impress him?

David Aaron Greenberg: Like, when you have a professor or a teacher that you really like and you want to do well, not just for yourself, but because they taught you, so you want to show them that you learned. It’s a weird thing. I don’t know. I think it’s just a human thing. The Buddhists would say that the students should surpass the master. Therefore, if the student doesn’t surpass the master, the master is no good. But I still wanted to paint all that time. But I wasn’t in art school. I didn’t go to art school. I had art lessons at Rutgers when I was a little, little kid. I did this special program.

AK: They still do that.

David Aaron Greenberg: Oh, really? And I learned how to do everything. And then when I was in elementary school, I had this teacher, Mrs. Jochnowitz, who just passed away this year. And she would take like two or three students that she thought were the prize, but she ignored everybody else. And then she would have us come in during recess like two or three times in the week. But what we did was learn batik and papier maché and oil sticks, and she just taught us everything. So it’s like why should I go to art school when I already knew how to do all this stuff? I wanted to study literature and art history. I think studying art history is much better. You can’t teach somebody to be an artist. You can’t teach somebody to be a writer. You either are or you aren’t. You can show them great examples, and that’s about it. Now, I regret that I didn’t go to art school because there’s shit that I have to call my young friends like, “How do I do this? Can I mix the linseed?” You know, like, I don’t know certain things that people learn in their first year.

AK: You know, there’s a hotline for painting where you can call a chemist.

David Aaron Greenberg: That just proves my point, that I probably should have went to art school. I have a studio that’s like a spitting distance from Rutgers campus. And you’re a Mason Gross grad, right? So, yeah, I just need Mason Gross grads around me telling me what to do.

AK: They taught us well.

David Aaron Greenberg: It’s a good art school.

Continue to Part 2

An Interview with David Aaron Greenberg (Part 1) Read More »

Interview