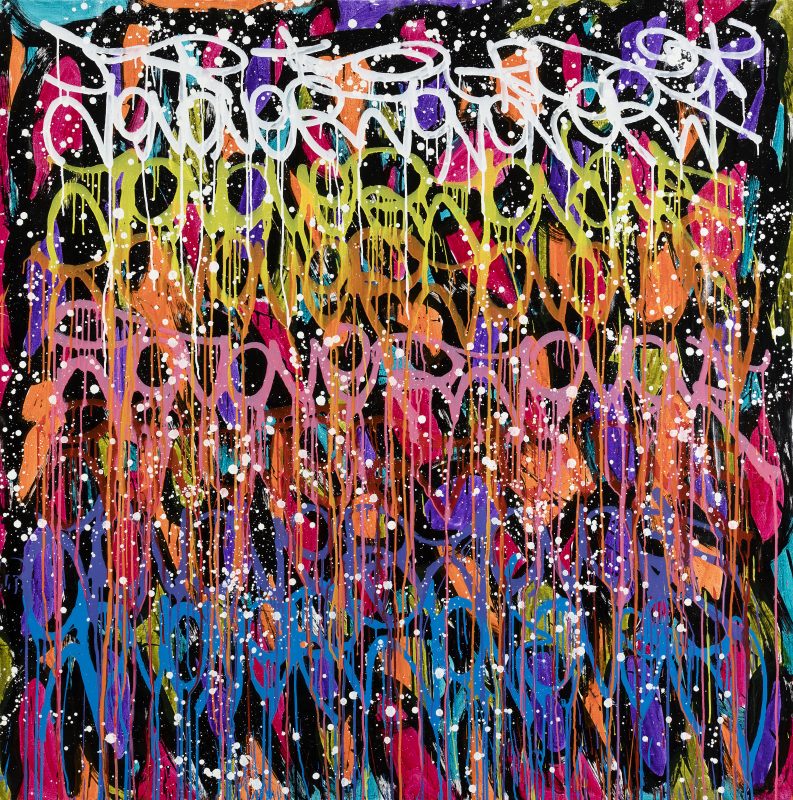

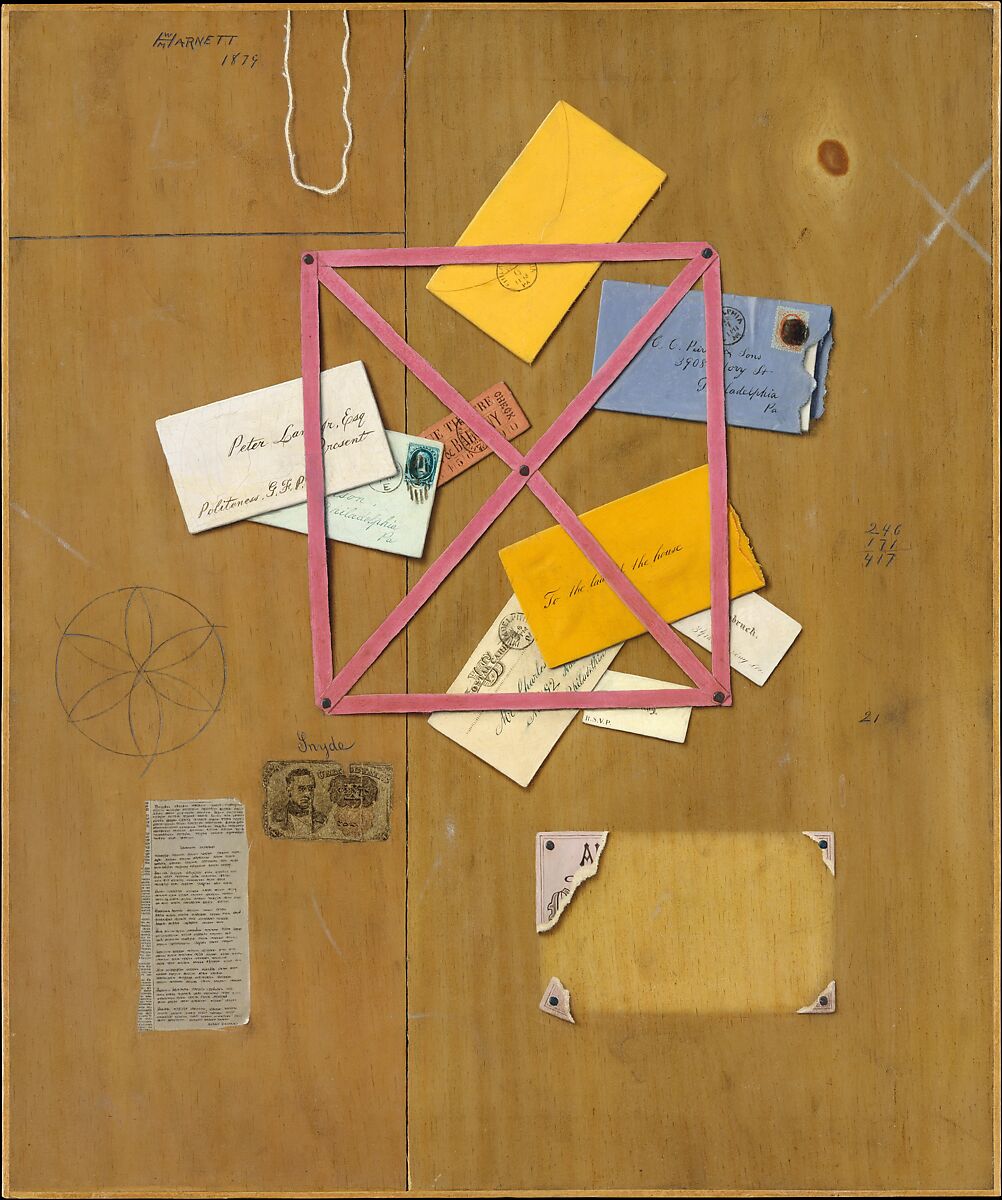

An Interview with JonOne (Part 3)

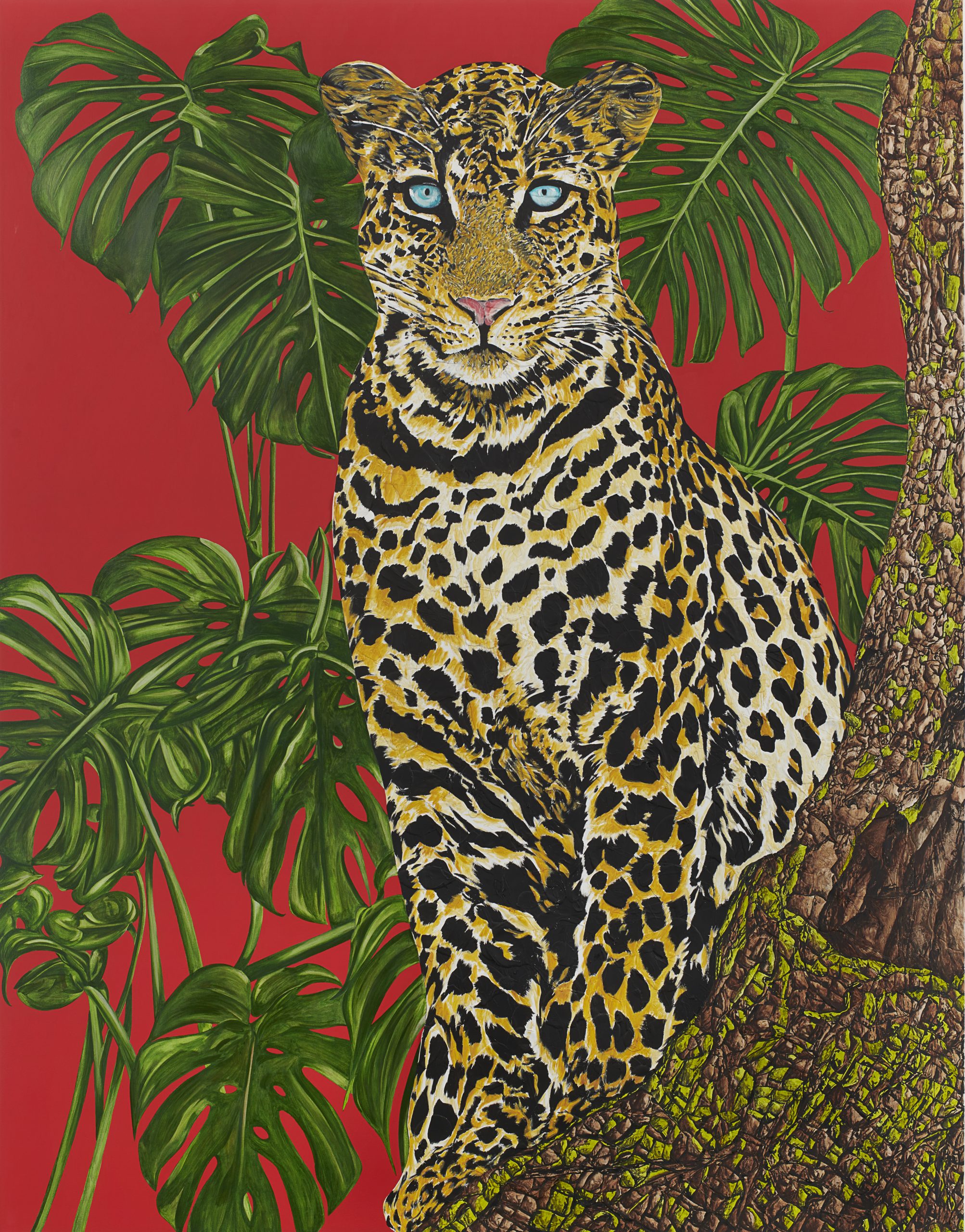

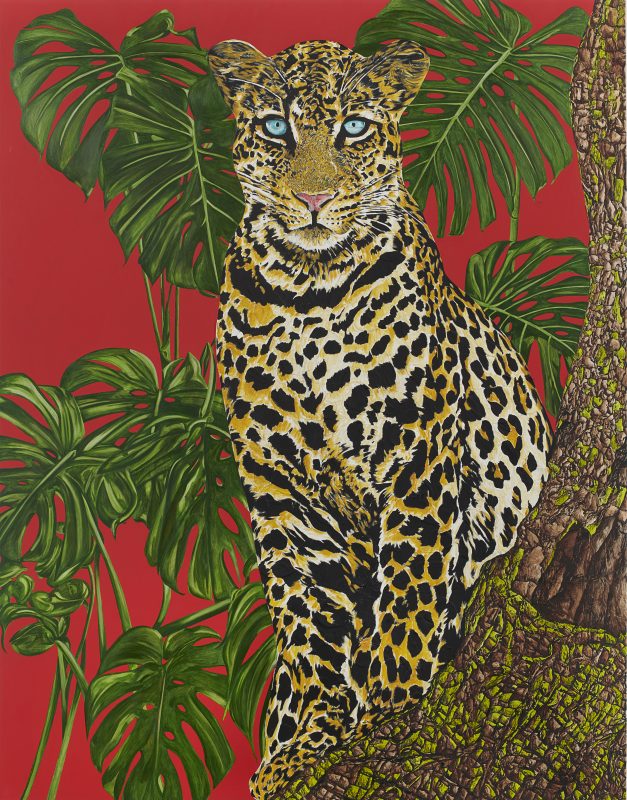

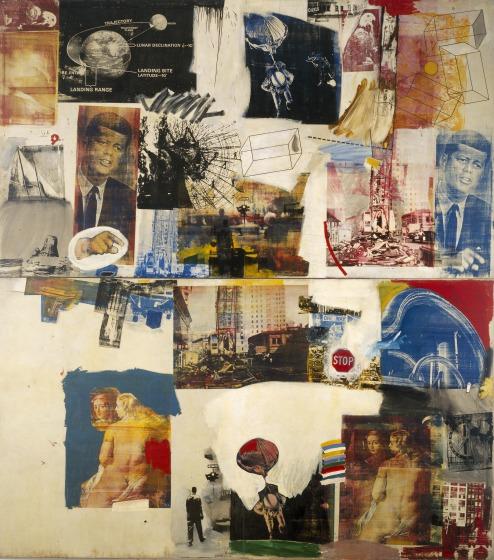

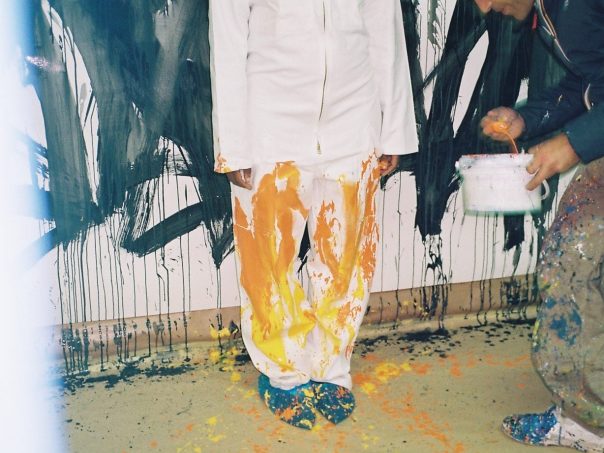

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

John Perello, AKA JonOne or Jon156, is an American graffiti artist living and working in Paris. In 1984, he founded the graffiti group 156 All Starz, before relocating to Paris in 1987, where he quickly made a name for himself. Working on a wealth of projects during his long career, and exhibiting on a global scale, his style is colorful and expressive.

In the final installment of their three part interview, Alexandra Kosloski and JonOne discuss “keeping it real” and his recent performance with the Trops.

Continued from Part 2

AK: It sounds like creativity and painting and art is necessity to you, but does it ever feel like a job? Is there a toll that it takes? You were saying there’s a lot of baggage and distraction as you age.

JonOne: No, no, no, no, I wouldn’t say it feels like a job. Because I know people that work, and I wouldn’t want to do what they do– even if they get paid a lot of money. I’ve already worked. I work so hard to be where I’m at today. It wasn’t easy. It was so hard to be free and do whatever you want to do. I mean, it’s just so hard to live off your passion. It’s extremely difficult.

And I sometimes tell people,“when was the last time you bought a painting?”. So few people buy paintings, and so many people are painting. So it’s just so difficult to survive as an artist. Of course, as an artist there’s different levels; there’s the blue chip artist and then the regular artist. Everybody defines their own way of being an artist. There’s no set rules, what works for you may not necessarily work for me.

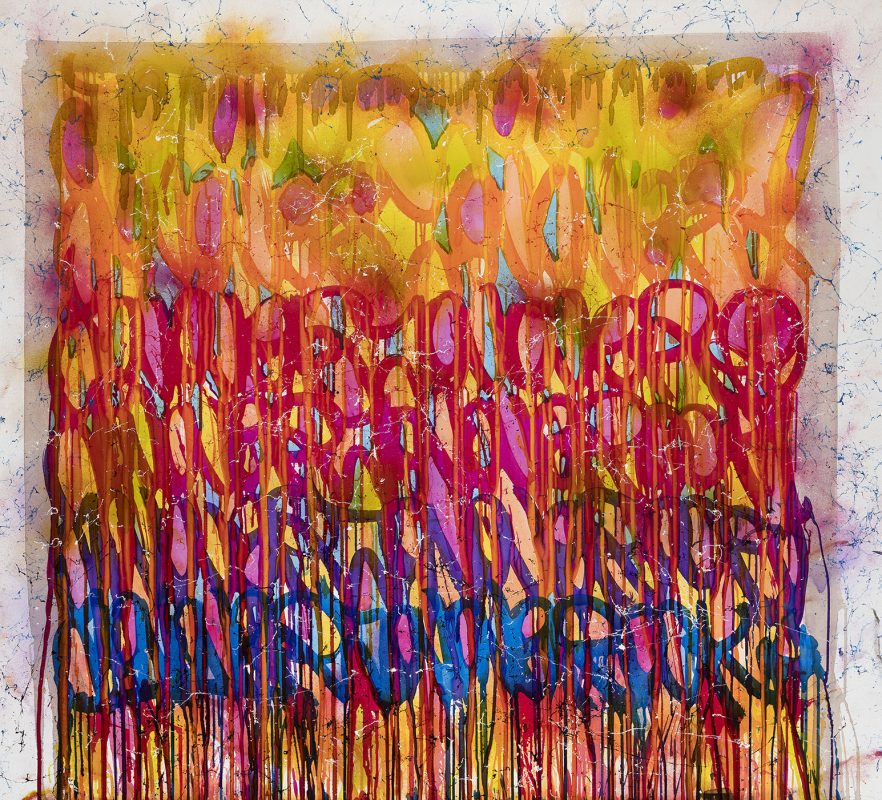

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

Like you may work in a gig gallery, and if I work at that gig gallery, I may find myself so bored working with those people, it would suck the soul out of me. So what works for other artists may not necessarily work for another artist. So everybody has to find their way to survive because… You gotta have a studio… life ain’t cheap. And painting is a rich man’s sport. The minute you start putting stuff in galleries, there’s a gallerist behind it and they’re trying to sell it. It’s not like a job but you’re selling your soul.

The thing about it is how do you keep it fun? How do you keep yourself always enjoying yourself? How do you protect yourself from people? You gotta protect yourself from people so you don’t get sucked into a system. One way or the other, people are gonna spit at you and you’re gonna spit at people. But how do you protect yourself from not being spit at so much? Because the minute you expose yourself, people are always gonna criticize you, tell you’re a sucker, you’re doing this, you’re a sell out, this and that. But how do you maintain your sanity? You know, because fame, money, and success can destroy a person.

So the way I am able to maintain my sanity and protect myself is through my art. And the process of painting has always been something that I enjoy doing, and that, nobody can take away from me. I protect that little joy I have from painting. That’s what I mean. The other part is just like formalities… It’s not formalities– but it’s just the things you’ve got to deal with because painting in itself is just 50% of the work. The other 50% is like selling yourself and seeing people and that’s something you got to deal with. But I try to enjoy that 50% is me. You know, that’s my part of joy. That’s why I don’t have chairs in my studio. So, you know, people don’t come and spend the whole day and suck my energy. So that part, that 50% belongs to me.

And I choose what I give to people. Say I gotta make some money– I’m not going to give them my masterworks. What people give me is what I give them. If you give me a certain amount of energy, then I give you back that energy, too. I’m not going to give you more energy than you deserve.

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

AK: You are very unique in that way because it feels like a lot of contemporary artists– like you said, it’s a rich man sport, so there’s this common path of getting a BFA and then an MFA and having this long vetting period where you’re not getting a lot of gratification… and you went a pretty different route.

JonOne: Yeah, definitely. I mean, I was like a street star when I was young. Sometimes when you get out of art schools and stuff like that, nobody really knows you, you got to build up, you may find a gallery– that helps. But I was already recognized for what I was doing when I was painting in the streets. Fame and success in my circle was something that I already knew. I just didn’t know the money part, you know. But fame was something I had to deal with when I was young.

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

AK: Do you think that the commercial aspects of the art world can affect an artist’s practice and how they produce work? And does it affect you?

JonOne: That whole word “commercial” is a big taboo. But you know, everybody has their own little situation going on. Some people don’t have to sell so many artworks because they have low overheads, or maybe they got rich parents, or the situation is just completely different. Maybe they have a business that has money coming in from other sources. And that’s not my case. Sometimes it’s hard for me to believe that I have so much responsibilities on top of me and so there has to be a matter of success and… selling, the whole aspect of selling. It’s a bad sign for me if all my paintings stay in my studio, you know, they have to come out of my studio. If they stay in my studio, it’s a bad sign. It means I’m going to have different types of problems.

I don’t really care what people say. I’m doing this for me. So what people think about me… you know…because those people who criticize you and things like that, those are the people that if you fall off, they’ll disappear in a second. They won’t be there for you. So I’m just worried for myself, really. Every day is just like “How am I going to keep the show on?”. And so that’s really my big, big, big concern every day. Because a lot of people switch off; sometimes they start doing paintings and then two years later they’re doing something else, another trend. But I’ve been doing this for so long and living off it for so long… that I give myself a pat on the back.

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photos by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

AK: So it feels like that’s kind of been your philosophy. That you’ve been unselfconscious and just doing it and then all the other things follow.

JonOne: Some people are really hard on themselves and they’re their worst critics. They let the exterior come inside the interior, you know, like criticism of people saying this and that. But I’ve been through so much shit that I come back down to earth. And I know where I come from and I know what I’ve done. I always come back down to earth. Like I don’t drive no fancy cars, I just try to have as much money as I can so I can pay people off, so I can be at peace when I paint.

But I know how it is, the starving artist thing. You know, when you try to keep it real…that word… “I gotta keep it real”. Shit… Like, yeah, I try to be open to opportunities, especially now to young people like you. I’m investing my time with you because I believed in you when I met you. So I say to myself, “you’re the future” and who knows what you’re going to do in the future? So I’m investing in you. I try to keep an open mind and not be like, “if you’re not writing for this magazine I don’t think it’s worth my time”. Just like you.

How many times has it happened to me that I’ve been like “Nah, I ain’t gonna do that,” and then that person becomes somebody humongous. Like, what a dumbass. You work with a lot of older people, established people. Shit. You never know what happens. You never know who’s who. You got to be open and flexible, you gotta be a little bit loose.

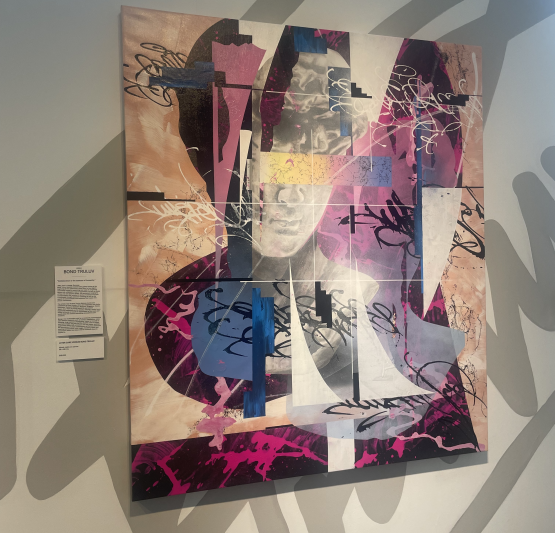

AK: So are there any current projects you’re really excited about?

JonOne: Oh yes. Well, I’m going to do a performance with The Trops. Just great. I’m really excited about that. Extremely exciting.

AK: Could you talk a little bit more about that or is it kind of a surprise?

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

JonOne: Not a surprise. Well… it’s sort of like a mystery. I’m pretty good at doing performances and getting people involved in my art that I do. Since I don’t let people inside my studio, it allows people to see the process of how I paint without revealing too much of myself. I kind of give them a little bit of the experience of what creation is about, and I think that’s a special moment. I remember being in studios sometimes, and just being there in front of artists when they were painting, and I would be like, “Wow, that’s so crazy”. So part of my performance is that. It’s just showing people the way I create these abstract images and opening up to my world. It’s going to be music, and I get into some sort of trance and yes, it becomes something really exciting for me to do.

JonOne

Performance at The Trops: Poesy

Photo by Adrian Crispin 2023 @adrian_crispin (IG)

An Interview with JonOne (Part 3) Read More »

Interview