Alexandra Kosloski: Can you think of a time that another artist surprised you?

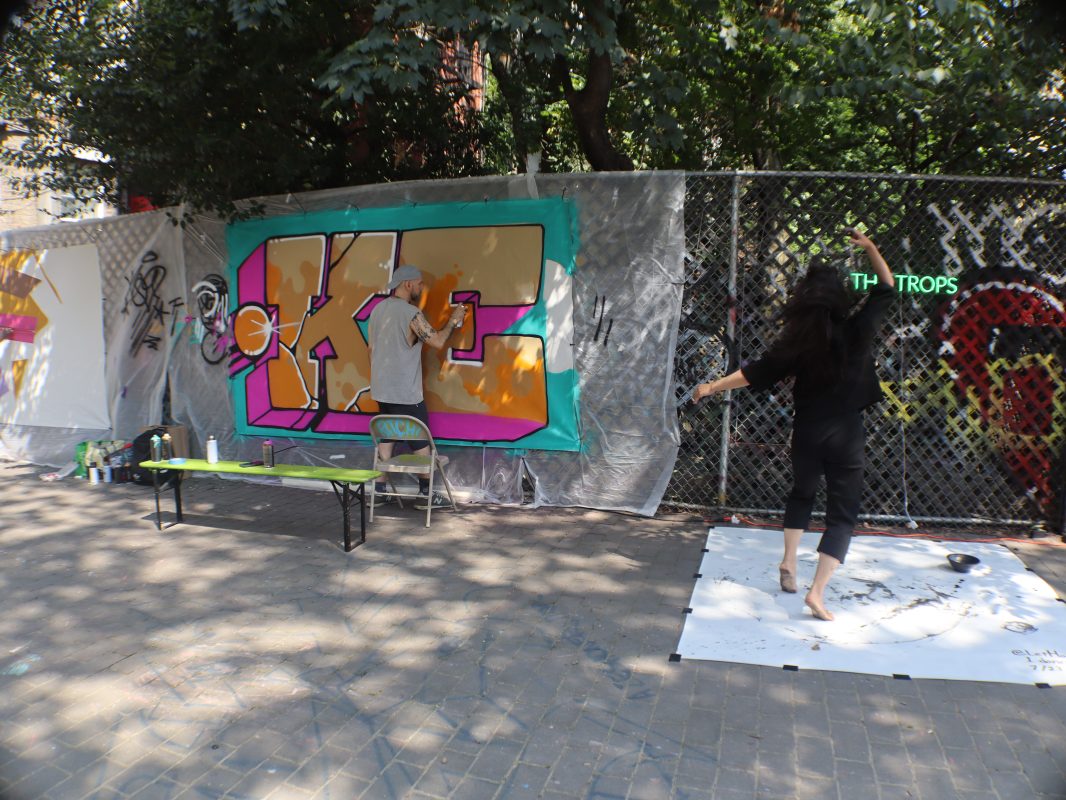

Nemo Librizzi: Oh, God. Artists always surprise me, so they never surprise me. I can give you three occasions. One was VFR, who’s a graffiti artist, and his specialty was “tagging”. His signatures were all over the city. VFR made a campaign to go all city [known for graffiti throughout all 5 boroughs of NYC] one of the highest ideals that a graffiti artist can realize, if you’re not going to concentrate on doing what we call “burners” [large, elaborate wall pieces]. When we first met, we were all selling fireworks down on Canal Street. My partner CHAMA saw talent in VFR that honestly, at that moment I felt was too raw. He was too young. But, at some point VFR matured. I don’t know what it was, but one day a light went on in his head. Suddenly he had one of the best signatures in the city and of all time. It shocked me to think the kid ended up being great.

I felt the same thing with the photographer, Khalik Allah. His videos for Wu Tang Clan seemed very straightforward, but he wasn’t coming from any poetic background that I recognized, he was pretty much self-taught. Somewhere along the line, he discovered these people on 125th and Lexington, who were smoking K2. K2 is supposed to be synthetic weed, but it takes people to a much more psychotic break with reality than marijuana takes somebody. Khalik Allah took it upon himself to document these outcasts, and it was like his soul was reaching out to theirs. These weren’t stars, or even conventionally “cool” people. Yet, there developed a very vital connection between the viewer and the subject. I think the resulting works are of great importance on the landscape of our city’s history.

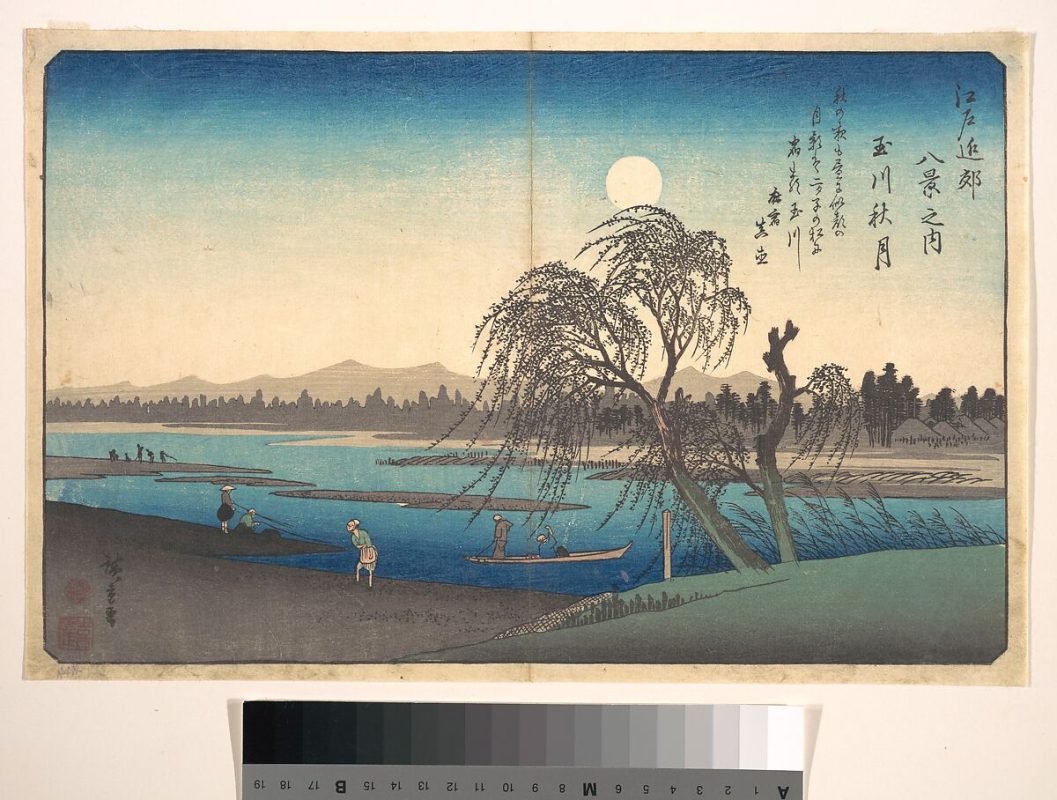

The third example is Martin Wong, because Martin Wong used to hang around all the graffiti scenes, and he was a very self-effacing, humble guy. Although he dressed pretty outlandish and had a big, larger than life personality, he was very earnest. I never knew him to be an artist, I just knew him to be part of the underground. He was an enigmatic character.

And one day, I was brought to see his paintings. It was his Chinatown series, and I had my mind properly blown. Martin Wong was probably the biggest Trojan horse for me in that he had always been there. I was friends with him. I’d hang out and eat dinner with him and I never knew how great of an artist he was until very late in his life.