Museum of Graffiti Features Layer Cake’s “Versus Project III”

When we think of artists, we don’t typically think of dangerous criminals. That is, unless you are a graffiti artist in the eyes of the law. Think property damage, felonies, and even jail time; yeah, now you have entered the high-stakes realm of graffiti. These creative risk-takers willingly partake in what many prosecutors would define as “criminal vandalism” in order to express their imaginations and opinions, typically based in social commentary.

But here’s the million dollar question- is graffiti truly vandalism, or is it a form of art? And where do policymakers and communities draw the line? These contradicting perspectives on graffiti enable some artists to be praised for their creative contributions, while allowing others to rot behind bars for the same form of self-expression.

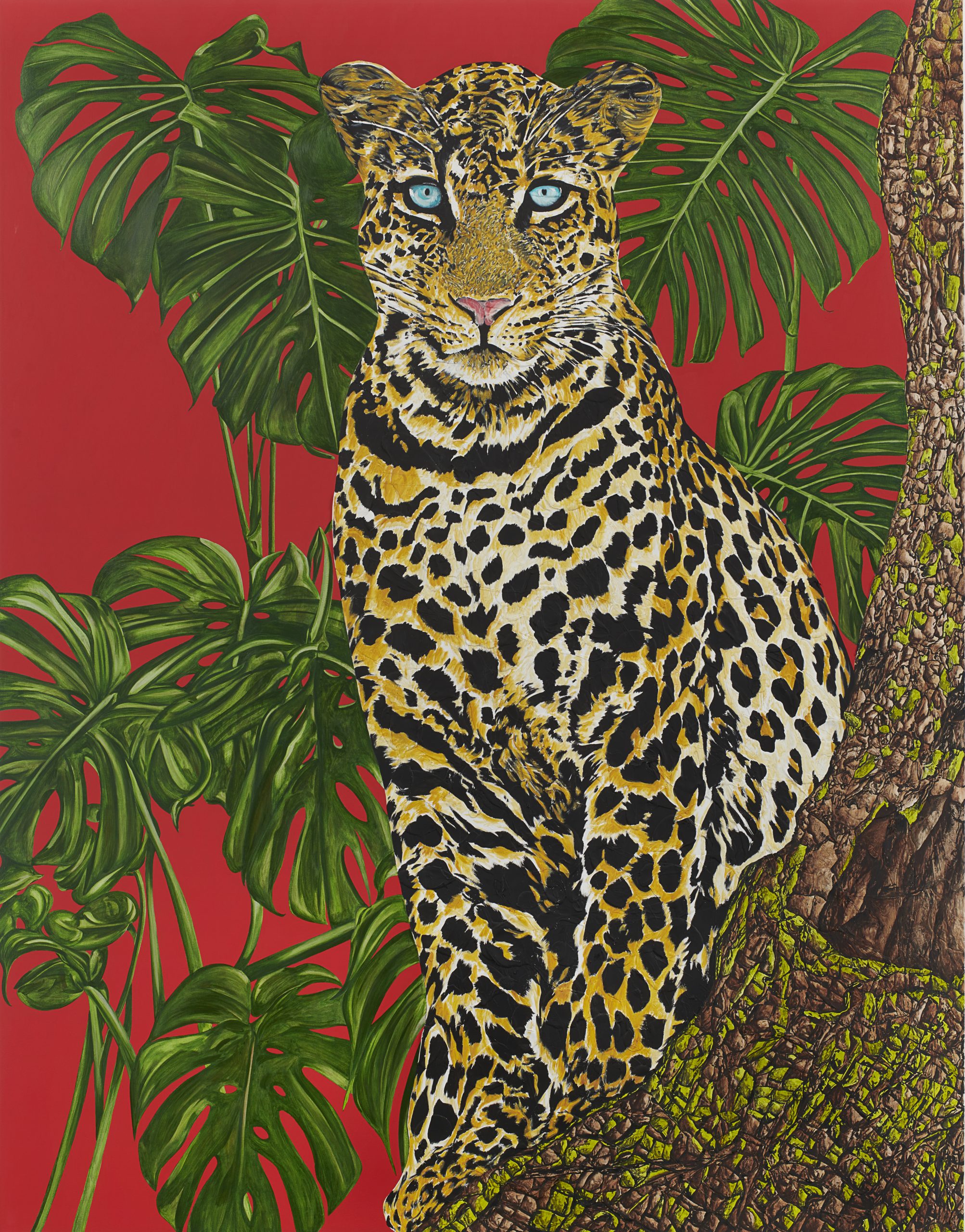

Today, graffiti is widespread and celebrated by many. It is even used for decoration, design, and merchandising purposes, especially in Wynwood – a popular entertainment district in Miami. Some of the world’s greatest street artists have left their mark on this neighborhood, transforming spray paint and marker pens into distinguished exhibitions of their heart and soul. However, in a society that cannot make up its mind, graffitists continue to endure an uphill battle of strict fines, courtroom proceedings, and even prison sentences in hopes of one day revising the definition of graffiti in the public’s opinion. Sure, these murals may be rebellious and bold in nature, but isn’t art just mimicking life? Graffiti has set ablaze an innovative art movement that has brought more beauty, color, and vitality than ever before to cities and neighborhoods all over the world.

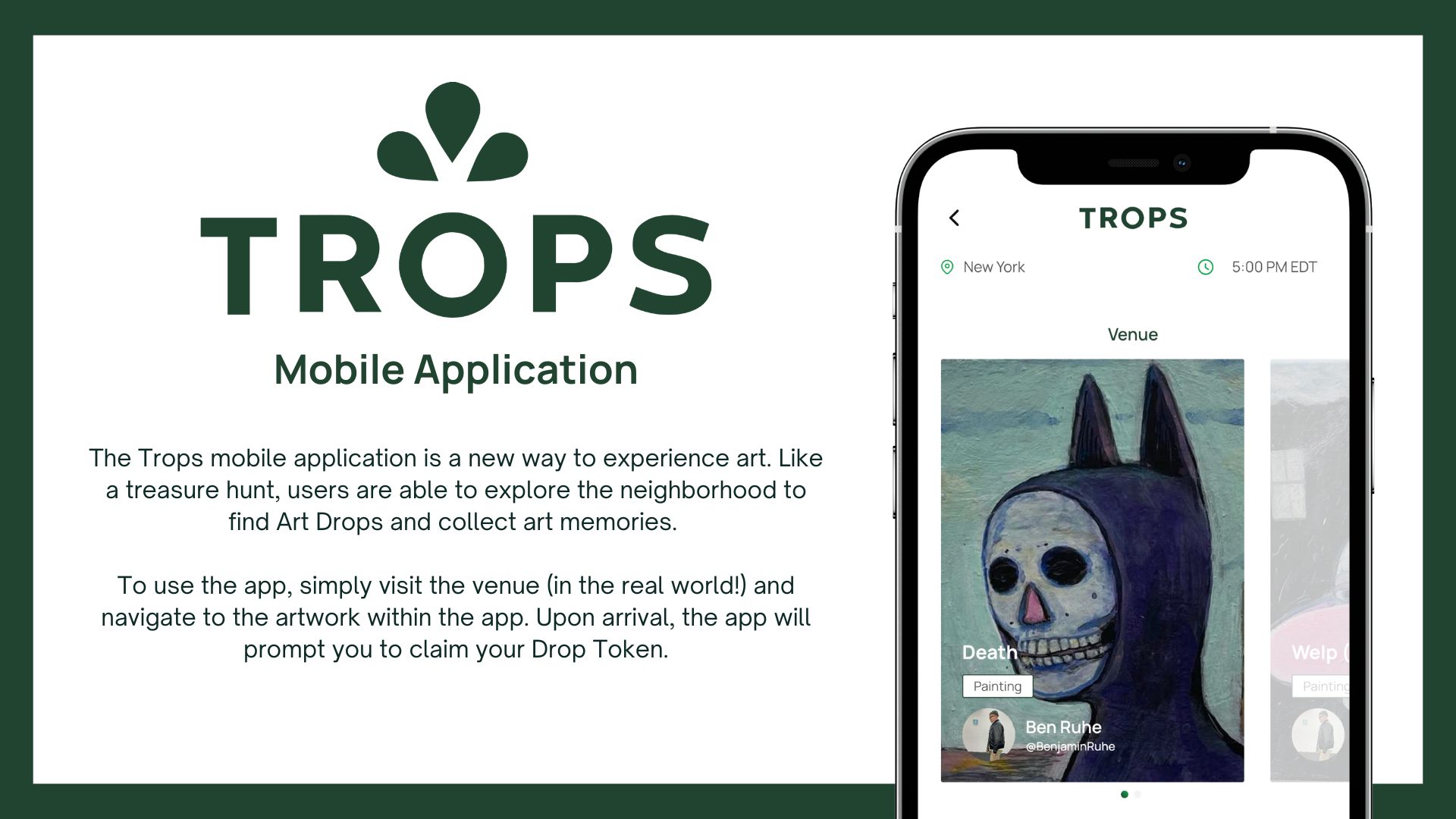

In honor of its significant history, the first ever Museum of Graffiti opened in none other than Wynwood, Miami, with the mission to preserve, celebrate, and educate people on the controversial style. Representing the world’s most talented graffiti artists, the museum offers general admission tickets for touring the contemplative works, at the accessible cost of $16. It also has graffiti classes for adults and drawing classes for children, led by local artists.

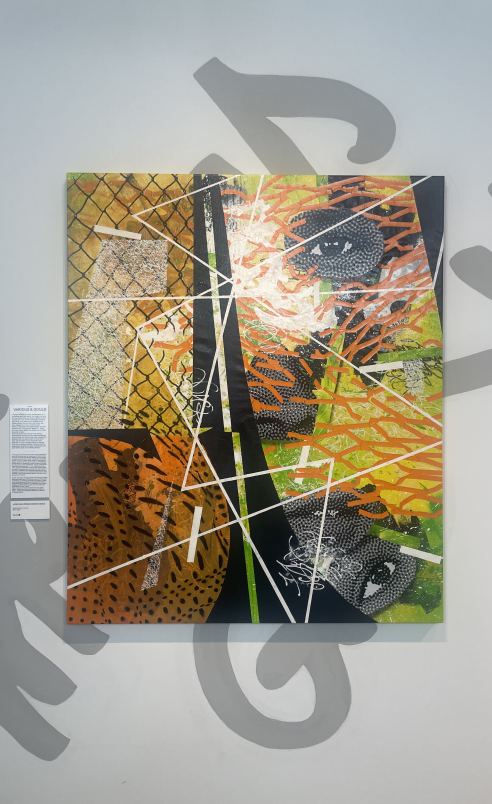

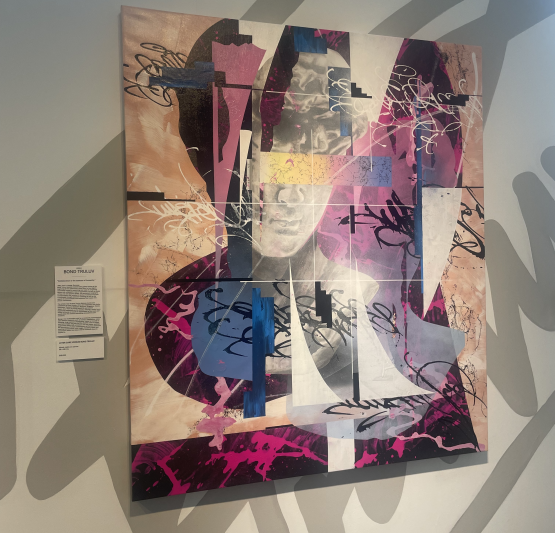

Currently on display at Wynwood’s Museum of Graffiti is the revolutionary Versus Project III, spearheaded by the artists Patrick Hartl and Christian “C100” Hundertmark, whose partnership is professionally known as Layer Cake. The project is a series of canvases that the duo started, but here’s where it gets interesting: Layer Cake left the canvases incomplete. The team then shipped their unfinished graffiti projects off to their favorite artists from across the globe to allow them to contribute – including Akue, Raws, Flying Förtress, Various&Gould, Bond Truluv, Thierry Furger/Buffed Paintings, Arnaud Liard, Rocco & his brothers, Hera & MadC.

Now, if this doesn’t sound right to you, that’s probably because the number one rule in the graffiti world is to never paint over someone else’s work. Typically, that is seen as a sign of disrespect for the artist and their message. However, Layer Cake’s Versus Project III takes a different stance completely. The spirit of the exhibition is rooted in collaboration and unspoken communication between the artists.

Without instructions or guidelines, the receiving artists were free to be as imaginative as possible on their collective canvas, combining their distinct styles with the artist’s markings before them. The exhibition maintains a high level of respect for each graffitist as they meticulously work with each other’s paint, merging all different techniques into one chaotically beautiful masterpiece. By layering signatures over one another, the spontaneous hybrid works well to pay tribute to contemporary art and graffiti as it brings the viewer into a dynamic world that embraces the beauty in differences.

From a distance, the Versus Project III is like a live battle for attention and space unfolding before your eyes, as you can almost feel each artist’s inner struggle as they were creating it. However, when you look closer at the canvases, you can see how no work is overshadowed or alone – every style and every color complements its neighbor. The intricate detailing and multitude of niche styles conveys a sense of movement, as if the piece is constantly evolving right in front of you. The final result showcases each artist’s unique perspectives and practices, while also uniting their efforts into an almost living and breathing piece of art.

As if witnessing a fluent conversation unfold through the adjacent approaches, the project implies a sense of unity, respect, and partnership. Explained by Layer Cake in an interview, this was the goal of their project- an exhibition that favors collaboration over competition in all aspects of society. Whether it be in the art world, or in the real world, cooperation is key to progress and harmony, says Layer Cake. And the Versus Project III, by demonstrating the importance of teamwork and trust, works well at encouraging this colossal theme for audiences to remember long after the exhibition is over.

It is through monumental installations like these that showcase the benefits of graffiti in modern society. Whether it be an inspiring mural on the side of a local business, or a joint-artist canvas hanging up in a gallery, spray paint never fails to make a powerful statement, urging social and political progress toward a brighter future. Does that sound like criminal activity to you? Well hey, you don’t have to take my word for it. Explore creative neighborhoods near you or check out the Layer Cake exhibition at the Museum of Graffiti to decide for yourself whether graffiti should be criminalized or celebrated.

Museum of Graffiti Features Layer Cake’s “Versus Project III” Read More »

Exhibition