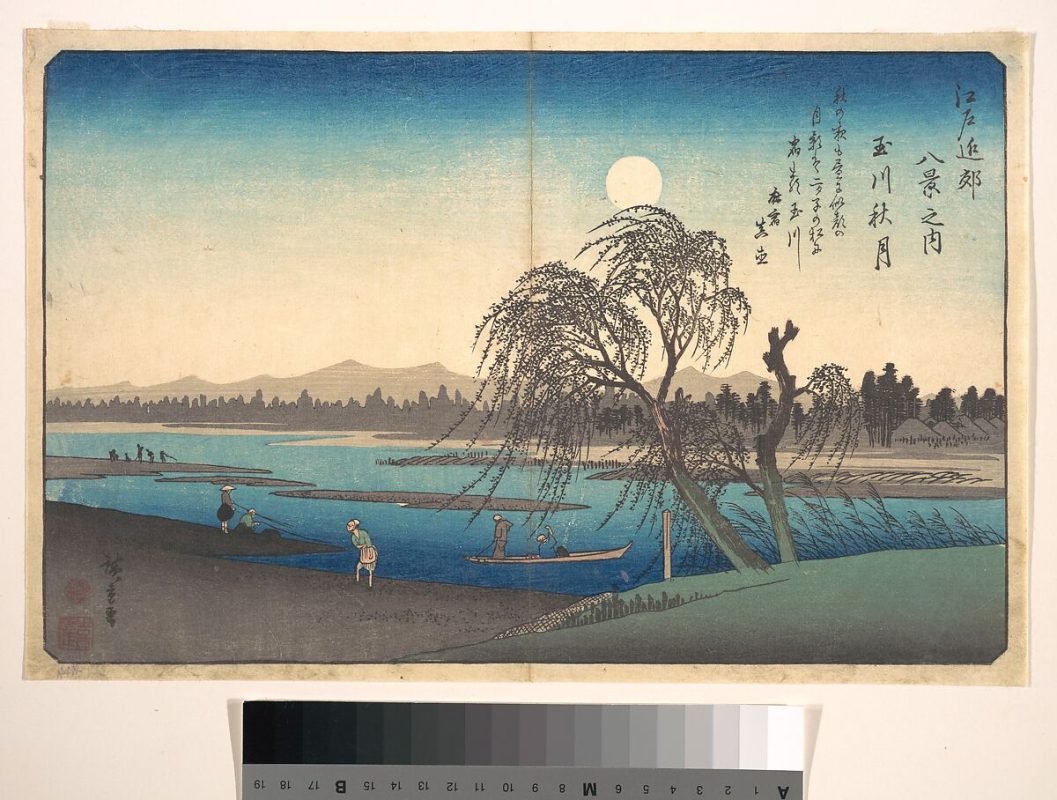

Barron Claiborne

Yasiin Bey with Turban

2009

Born and raised in Boston, Barron Claiborne moved to New York City in 1989 assisting photography legends such as Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Gordon Parks. Nathalie Martin spoke with Barron about what informs his practice, the limits and reaches of photography, and the importance of constantly creating. Claiborne reflects on self-taught mastery and how his extremely honest, critical, yet sensitive eye has landed him in permanent collections all over the world, including the Polaroid Museum Cambridge, the Brooklyn Museum, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and MoCADA.

NM: How did you get started in photography?

Barron Claiborne: My mom found a camera in the bank and gave it to me when I was a kid.

NM: Really? In the bank?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah.

NM: Where your mom worked?

Barron Claiborne: No, my mom was a nurse. She was in the bank one day and she found it.

NM: And she just handed it to you saying, “You would be into this, here you go?”

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, well, she just gave it to me as something to do. When I was 10, she was like, “Here, take this,” and gave it to me, and I started reading books about photography and shit like that.

NM: So, you were first exposed through your parents? Or through school?

Barron Claiborne: My mom. Then I went to school and I learned more. There was a darkroom in my high school, it was old, and no one used it. Me and another kid rebuilt it and started using it. We would take pictures and they put them in the yearbook. Then I would take pictures of myself and my friends. I always did studio pictures – I didn't really shoot outside tons or anything. It was always people.

NM: Studios and sets?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I like taking pictures of people and messing with sets.

NM: You were immediately drawn to portrait photography?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, totally. Because you have people constantly around, it’s the easiest shit to pull off.

NM: Totally. And it was just capturing moments with your friends?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, but less spontaneous, most of it was set-up. I would do shit like – I used to do this thing where I would set up a little tripod and a trampoline, and I would have my friends jump over the camera and take their pictures when they were landing upside down. I used to do dumb shit like that. All kinds of stuff.

NM: When you were practicing in high school, redoing dark rooms or whatever else – do you immediately know you wanted to take it seriously and go to art school?

Barron Claiborne: I was going to art school anyway. I didn't really do much photography in art school, because by the time I got there I had already been taking pictures for around eight years. So a lot of the stuff they teach you those first years, I already knew it, and I really didn't want to go over that shit again – like dark rooms and shit like that. I didn't want to at all.

NM: Did you start experimenting with different mediums?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, definitely. I used all kinds of shit. I would make shit out of everything. I used to do collages. I just like doing visual things. But then I was working at restaurants and doing other shit and then one day I was like, “I should just do photography, fuck it.” You know, then everyone cautions you against being an artist, saying shit like, “You got to get a job, you got to have a backup.” Or like, “You should join the military,” or “They have really good jobs in the post office.” I was looking at them like, you’re crazy!

NM: “Yeah, work for the government!”

Barron Claiborne: Right, work for the government. Because they assume the government will always be there, so you’ll always have a job. But I never wanted to do shit like that.

NM: I remember getting told this when I was younger.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, or they try to get you in the military. My family has a lot of people in the military. I was not going into the fucking military. Even my uncles who were in it, they were like, “Do not go into the military.” Because they knew I’d end up in jail. They were like, “Oh you’d get court-martialed.” Easily.

NM: Did you think experiential learning– especially as a photographer– and just taking photos every day was more beneficial to your practice and you as an artist than school was?

Barron Claiborne: Oh yeah, of course. I’d already been doing that. And also, I didn’t like working for other people. I always knew I couldn’t. Even when I was a kid. I used to have jobs. I’ve been working since I was like 10. I used to mow lawns, deliver paper, all that kind of shit. But I realized I could never work with anybody.

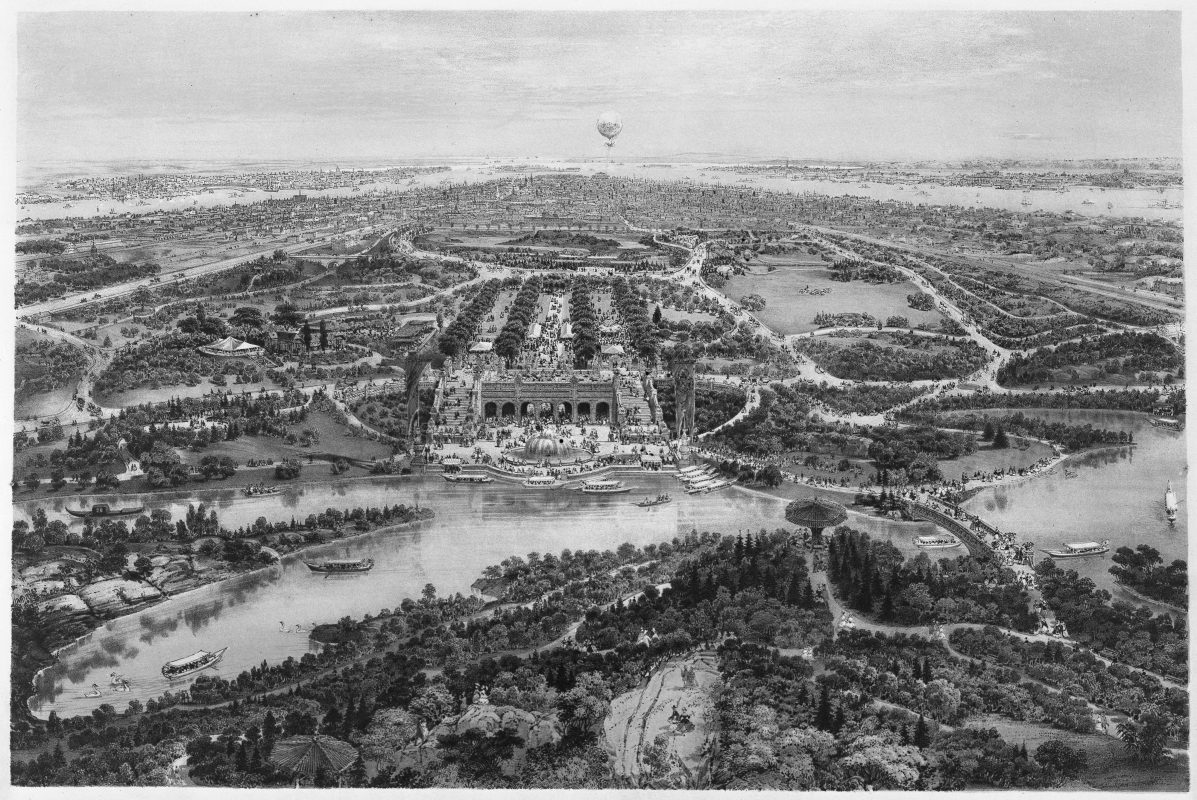

Barron Claiborne

Domino

1992

NM: So it was born out of like –

Barron Claiborne: It was just born.

NM: Out of necessity? Or internally, it was always there?

Barron Claiborne: It’s just me. It’s just the way I am. I don’t know where it comes from. I never liked any authority, even when I was a little kid. Always. It just seemed weird to me.

NM: Maybe that’s why your mom handed you the camera. She knew. She was like, “Here you go, play with this.”

Barron Claiborne: She knew, yes! It’s a weird story, right? Literally got my living from my mother. Literally. I think about that. I think it’s funny.

NM: So as you started to learn about photography and the history of art, who were your main influences?

Barron Claiborne: I always loved Richard Avedon, Gordon Parks, Irving Penn.

NM: Who were your mentors, as well.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I got to meet them, was the great thing. There’s a Mexican photographer, Manuel Alvarez Bravo. I really love his photos. I used photos in medical dictionaries, other weird shit, photos of flowers. My favorite book is the book of photos from all over the world, and the book is called Anonymous, because they don’t know who took the photos. Only a couple of them they know, but the rest of them, no one knows who took them. And the photos were beautiful. When I was a kid I would always be like, “Oh, I’d love to have my photos in a book and no one knows they’re mine.”

NM: So it wasn’t “I want everyone to know my name.”

Barron Claiborne: No, I don’t care about that. I didn’t really like – I was getting sort-of well-known, and I don’t like it that much. I don’t like when people call me by my first and last name and stuff like that. I don’t like it at all.

NM: Right. You as a brand, rather than a person.

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, exactly. It made me feel uncomfortable. That’s why I stopped taking pictures of celebrities, and I kind of stopped doing music videos and stuff like that. It just bored me. Because I want to do my own thing. I don’t really care about doing other people's thing.

NM: That’s interesting, because of all the collaborative work you’ve done.

Barron Claiborne: Lately, I’ve been concentrating on collaborative work.

NM: But I mean in the past, even for publications, music videos, album covers – was that a different process for you?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I still try to get the same feeling as my personal work. I don’t differentiate my personal work.

NM: The process stays the same?

Barron Claiborne: I do the best I can in a commercial setting. Because you can’t do the same work, it’s different. But those aren’t the photos that I like. I like the photos I do on my own because I've been taking pictures since I was 10. I have a lot of pictures. There were times I took pictures every day, all day for 10 years. Whether I was working or not. And I was using large format, so I don’t have as many pictures as when people use 35 mm. But I have a huge archive from all over the place. And I’ve used all kinds of cameras– toy cameras, plastic cameras, 8 x 10, 4 x 5, underwater ones– everything, everything. I like all of them.

Barron Claiborne

Notorious B.I.G as The King of New York

1997

NM: When you were doing collaborative work or working with musicians, did you just find yourself in those spaces? Was it for money?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, I was really poor. Of course, when you’re first starting you get a bunch of rejection, but then you finally get a job, and it never paid a lot, but I was broke so 300 bucks was great. Then you get more and more. Then you realize magazine work only gets you more work, it’s sort of like advertising for you, it gets people to know your name. Then I realized, for a long time, because no one had seen me and all they would see is my name, they all thought I was an old white dude, which I thought was kind of funny. I remember once I went to Paris to work, and dude, they couldn’t find me in the airport until I was like, “By the way, I’m a black dude.” Then they found me. Because they were looking for some old white guy! They were like, “It’s because your photos seem so old.” Back then, I was using the 8 x 10 and most of the stuff was large format polaroid and shit like that. So I never even thought of that. But my name is pretty waspy, I guess.

NM: But then they meet you, and it makes total sense.

Barron Claiborne: Oh yeah, I’m super waspy. I’m a waspafarian.

NM: You mentioned Avedon, Gordon Parks and Irving Penn. Those are big names. How did you come into company with them?

Barron Claiborne: Well, I just saw books as a kid, and then when I moved to New York, I assisted for a while, so I got to assist them. But I met Richard Avedon in Boston.

NM: How old were you when you came to New York?

Barron Claiborne: I was 21, 22.

NM: From Boston straight to New York?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah. I met Richard Avedon in Boston, at his exhibit, because I worked at the Museum of Contemporary Art. He had that “Out West” show there. I actually got to meet him and talk to him. They were hanging the show, he came, it was pretty cool. And then when I moved to New York, I assisted wherever I could. That’s how I met other ones, like Irving Penn.

NM: You just hit up Avedon asking if you could work for him?

Barron Claiborne: Yeah, right when I moved here, you fill out the application, they have you come in. Sometimes you would replace guys you knew who were assistants when they couldn’t work. And two of my friends worked for Irving Penn. I substituted for both.

NM: Friends from Boston?

Barron Claiborne: No, actually, New York photographers that I met early on. Yeah, when you first start out, you hang out with photographers. Over time, it changes, because people are going for money, for their career. And then you become competition. So then they get weird. But at first, you’re surrounded by photographers. We were always going to the lab. Loaning each other cameras, going to each other’s studios.

NM: Right, it was a collective.

Barron Claiborne: Yes. Because we needed it to survive.

NM: Absolutely. When you were doing music videos or album covers, was that the scene you found yourself in? Or did music really inspire your work?

Barron Claiborne: No, people would ask me if I wanted to shoot so-and-so, sometimes you didn’t want to because you didn’t like their music and were just trying to give them a good photo. I’m doing my own thing – I don’t tell you how to do your music thing, that’s your thing. You don't tell me how to take pictures. I don't tell you what to put in your music. But as you go higher, people always try to tell you what to do. Which is one of the things I hated. Because then you end up taking pictures for money, and you don't like photography anymore. I saw that happen to some of us. They started making money, and then they just started taking photos for the money. But then you don't like photography. I've been taking photos since I was ten. It's so natural. I wouldn't want to not like it, you know, so I just stop taking those jobs.

Continue to Part 2